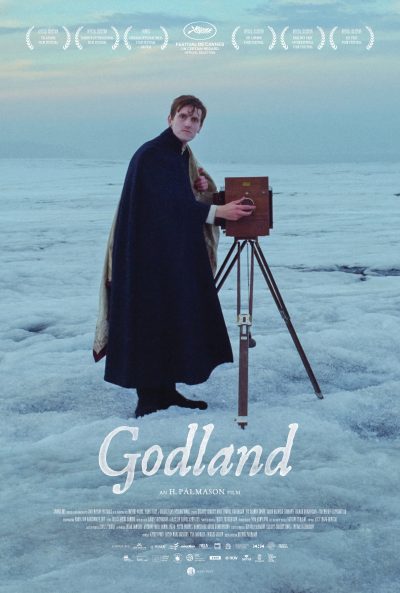

“Godland” (“Vanskabte Land”/“Volada Land”) (2022 production, 2023 release). Cast: Elliott Crosset Hove, Ingvar Sigurðsson, Jacob Hauberg Lohmann, Vic Carmen Sonne, Ida Mekkin Hlynsdóttir, Hilmar Guðjónsson, Waage Sandø, Snæbjörg Guðmundsdóttir, Svanavatns Jökull Darri. Director: Hlynur Pálmason. Screenplay: Hlynur Pálmason. Web site. Trailer.

In the late 19th Century, Father Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove), a young, idealistic Lutheran minister living in Denmark, is about to embark on a grand undertaking – building a new church in a small colonial community in Iceland, which at the time was under Danish rule. He approaches the assignment with great enthusiasm, looking upon it as a bold adventure, an opportunity for discovery and a chance to practice his hand at his personal passion, photography. He’s heard tales of the wild, untamed Icelandic landscape and its colorful people, both of which he’s eager to see firsthand. In fact, he’s so inspired by the prospect that he passes up the opportunity to sail directly to the community where he’ll be carrying out his mission. Instead, he seeks passage to a remote location on Iceland’s southeastern coast, poised on the opposite side of the island from where he’ll end up. He uses this impromptu port of entry as a jumping off point to cross the vast and diverse expanse of his new homeland so that he can see everything it has to offer while making his way to the stage where he’ll meet his destiny. He sees it as a chance to survey the land, meet the locals and document it all with his camera. Little does he know, however, what he’s in for.

Fr. Lucas soon discovers that the moniker “Godland” is a fitting name for his new home, at least as God is described above. In many ways, the unrestrained nature of the Icelandic landscape is more than he bargained for. As the cleric crosses the island with his translator (Hilmar Guðjónsson) and guide, Ragnar (Ingvar Sigurðsson), he soon finds that the diverse, challenging terrain and environmental conditions test his endurance and resolve. In his experience of nature (i.e., “God”) in its unleashed state, he finds that the wild character of this place is far different from the more genteel way of life that he had grown accustomed to in Denmark. In his arrogance, he also soon learns that life in Iceland can’t be “tamed” in the same way as back home; in Godland, the unconstrained will of the divine can’t be made to bow to man’s whims in the same way as it may be within the civil confines of a lavish parish on the European mainland, sometimes with dramatic or even tragic consequences.

In addition to the environmental conditions, Lucas soon finds that the residents aren’t quite what he expected, either. While some are genuinely friendly, caring and compassionate under trying conditions (especially the women), many of the men are cold, gruff, and not especially sensitive to the preacher’s needs and more worldly outlooks. In large part, this attitude is attributable to the Icelandic way of life, one in which the residents’ resilience and fortitude is frequently tested by the challenges of everyday life. Fr. Lucas also soon learns that the Icelandic natives aren’t particularly fond of being under the thumb of Danish colonialists. They’re reluctant to embrace Danish culture and often deliberately and defiantly speak in their own tongue to keep settlers in the dark as to what they’re saying. Needless to say, it’s not the warm welcome the minister expected.

Crossing the island proves to be more challenging than Lucas ever expected. In fact, by the time he arrives at his destination, he’s in a seriously depleted and sickly state. He’s taken in by one of the settlers, Carl (Jacob Hauberg Lohmann), who lives in a comfortable farmhouse with his two daughters, Anna (Vic Carmen Sonne), an unmarried young woman who serves as a sort of surrogate wife and mother, and Ida (Ida Mekkin Hlynsdóttir), a teen who attends to many of the farm chores and is an aspiring amateur musician. The family attends to the minister’s needs, nursing him back to health so that he can get on with the business of building his church.

But, as Lucas heals and regains his strength, it soon becomes apparent that he’s begun to experience the effects of living in Godland. The preacher’s demeanor begins to change, showing signs of coming under the influence of the wild, untamed nature of the divine in this unrestrained and often-unforgiving land. He’s more prone to giving in to his emotions, something he was once far more reluctant to do. And, as feelings begin to emerge that he’s unaccustomed to, he finds himself torn in terms of trying to understand himself and this new expression of God that has begun to take over his life. It’s something with which he’s obviously uncomfortable, probably because it’s so unfamiliar to him, testing his faith in ways he’s never experienced. He’s unsure how far he should let himself go: Should he hold on to what he knows, or should he give in to this previously unexplored aspect of God that’s apparently an accepted way of existence in Iceland? Indeed, when in Godland, should he do as the Godlanders do? It’s a spiritually evolutionary journey for which he was unprepared, and now he must decide what to do about it.

This represents a fundamental distinction in the beliefs held by the locals and the colonists. The Icelanders understand that their God is a wild, untamed force, one filled with an infinite number of possibilities available to it for helping mankind work out its challenges and aspirations. The solutions may not always be easy, as evidenced by the Icelandic way of life, but the residents are confident that things will work out in the end. They have faith in the process. And, by viewing this relationship as a partnership, they see it as a means for cooperation and collaboration.

This is one of the key principles driving the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon our thoughts, beliefs and intents in conjunction with the power of God/the Universe/All That Is in manifesting the reality we experience. The locals may not be fully conscious of this way of thinking, but it seems that they accept it as an underlying assumption about how life works and how they relate to the divine (and vice versa).

Fr. Lucas and his immigrant countrymen, by contrast, have yet to fully understand and embrace such thinking. And, in their supposed desire to learn more about the outlooks of the locals, they tend to be somewhat dismissive of these “simpler” views. (After all, how could those perspectives be valid for a people who don’t even have churches and other religious trappings to define their spiritual existence?) In that sense, their arrogance and allegedly “superior” mindset prompts them to discreetly look down their noses at the island’s native residents. This becomes apparent, for instance, in one scene when the usually-crusty Ragnar – typically a man of few words, especially those of a personal nature – seeks to confess his failings to Lucas, who pays him little mind and even tries to silence this obviously “inferior” individual.

However, accepting this alternative spiritual view is at the heart of what’s playing out in this story. Fr. Lucas, like many of his fellow colonists, is learning how to view God in this same new light, a cornerstone of his spiritual evolution, one in which the divine is an integral, incorporated element of daily life and not something exclusively reserved for Sunday mornings. It’s about how someone lives his or her life every day, an integration of the divine and the terrestrial in harmony on an ongoing basis.

To fully grasp this, there are several key principles these new disciples need to understand. To begin with, the Universe cooperatively helps make everything possible, for better or worse. The seeds of every conceivable possibility are contained within its makeup, and we have access to all of those resources, without limitation, in determining how things ultimately unfold. What we do with what we’re provided plays an important role in this, given that the divine supplies us with the means to achieve our goals, whether or not we recognize (and embrace) them as such.

These are key principles for Fr. Lucas to examine. It often proves difficult, however, given that he comes from a “sophisticated” and “civilized” society, one that has grown impressed with itself and its accomplishments, most of which have come to be perceived exclusively as the result of mankind’s own handiwork. In adopting that attitude, however, the minister and his peers have lost sight of how these manifestations actually came into being as divine/human collaborations, a perspective the islanders have retained.

As a result, when things don’t seem to work out, Lucas often tries to force results into existence, often with less-than-satisfying results. This is known as “pushing the Universe,” and it seldom works out as hoped for. In the fulfillment of our ambitions, God (as viewed in Icelandic terms) may appear to have thrown us some curve balls on the way to reaching our destination, developments that might be easily dismissed. However, there may be elements imbedded within those twists and turns aimed at taking us where we want to go – provided we have faith in those notions and are willing to follow through on them to see where they lead us. Human arrogance can indeed thwart the divine’s plans to help bring us what we’ve asked for, and those unwilling to take this to heart may pay a high price for such conceit.

Applying culturally and environmentally based considerations can have a tremendous impact in these situations, too. For example, the differences between Iceland and Denmark in these areas are considerable. In some respects, the Icelanders live lives more tied to their surroundings. In some ways, this has left them more open-minded (and, consequently, somewhat more liberated) than their Danish counterparts in such areas as romantic relationships. As Lucas assimilates into the island culture, he finds himself increasingly drawn to Anna, something he resists as it represents what he believes to be falling prey to the temptations of the flesh, inappropriate behavior for a cleric. Meanwhile, Anna – even though Danish by background – has had some time to fit in and has grown more comfortable with the local culture, including a more relaxed view of romantic matters, even with a supposedly forbidden prospect like a priest. Accordingly, relationships in the Icelandic view are seen as a natural part of life, one of the joyous and wholly acceptable gifts bestowed by the Universe, so why not pursue them when the opportunity arises? Anna thus feels free to engage in something that’s assumed to be perfectly natural while Lucas struggles with the cultural baggage he’s brought along with him from home. This, of course, raises the question, “Does God really want one of His own children to needlessly suffer the pain of loneliness, or does the divine truly want us to experience the joy of love and companionship?” (I’ll go with the Icelandic view on this one.)

Lucas also needs to understand – as the Icelanders apparently do – that life is meant to be lived in the moment, that the point of power is in the present, not some past that’s already gone or a future that’s yet to arrive. The local residents, for example, realize that it’s fruitless to think about tomorrow when confronted with solving a problem that’s at hand in the present. Worrying about what might happen in the afterlife when faced with figuring out how to traverse a mountain peak or avoid an erupting volcano (with the divine’s guidance, of course) is comparatively trivial when such present challenges arise.

Similarly, it’s important to recognize that the present is a fleeting moment, one that goes almost as quickly as it comes and one that’s impossible to capture forever. Lucas seems to have some difficulty with this, too, as evidenced, somewhat ironically, by his passion for photography. As admirable as this pursuit may be, it needs to be properly tempered. In some ways, his interest in this subject almost seems to be based on the idea of wanting to create an enduring record of the moment, freezing it as if it will somehow last for eternity. But will it? The photo may live on, but the moment won’t, and the distinction between the two needs to be recognized. Again, this is another lesson that Lucas could learn from the locals.

All of the foregoing notions are meant to provide the young minister with an experience of spiritual evolution, learning how to engage in an existence with a practical, accommodating partner, not a remote abstract concept, one that is a wholly integrated part of everyday life. It’s about learning how to let go of human hubris and to become a full-fledged collaborator with the divine that allows us both to come to know ourselves, an equal partner in the grand experiment of reality creation. In essence, it’s all about seeing God in a new light. It would indeed be in Lucas’s best interests if he could come to see the difference between this option and the one he has long known and followed. For my money, if given the choice between a joyful, fulfilling experience and one riddled with limitations and perceived capriciousness, it’s not too hard to figure out which one I’d choose. For his sake, let’s hope Lucas does the same.

What is God? Is it a reasoned, rational civilized entity or a wild, untamed force full of unbridled power in search of becoming a willing collaborator with us? And, in light of that, then, what kind of relationship are we supposed to have with this elusive divine enigma? That’s one of many unexpected challenges raised in this fact-based story from 19th Century Iceland. Life in a new land composed of unfamiliar elements tests the wits, patience, and, above all, faith of a young, idealistic immigrant cleric as events unfold in unforeseen and potentially disturbing ways. It’s an evolutionary journey for which he’s unprepared and often unable to fathom, prompting him to question much of what he believes and how he conducts himself. The result is a thoughtful meditation on these issues, featuring positively stunning cinematography, fine performances and superb production values. The pacing is surprisingly well balanced, too, especially for a film with a 2:23:00 runtime (though some of the picture’s montages – as beautiful as they are – probably could have been dialed back somewhat without significantly impacting the finished product). Writer-director Hlynur Pálmason’s latest is arguably his best work to date, but be sure to give this one the time that it deserves to develop in order to thoroughly appreciate and enjoy it, both for its sheer beauty and for everything it has to say about the divine and the place it occupies in our lives.

“Godland” has been showered with numerous accolades at various film festivals, receiving multiple awards and nominations in myriad categories. Most notably, the film captured an Un Certain Regard award nomination at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival. In addition, at the 2022 Chicago International Film Festival, this release received the Gold Hugo Award for best feature and the Silver Hugo Award for best cinematography. And, thankfully, even though this offering has primarily played the festival circuit, it’s now available for streaming online.

While our impressions of and relationship with the divine is ultimately a highly personal matter, it’s comforting to know that we have a huge array of options available to us in determining what forms those issues will take. We can follow conventional interpretations that have been prefabricated for us in terms of beliefs, liturgies, dogma and strictures, and that may genuinely be enough for some of us. But, for those who are captivated by the wonder of existence, it’s possible to embrace a limitless view, one in which restrictions have been removed, leaving us to determine for ourselves what best suits our innate sensibilities. Getting to that point often involves a spiritual journey, one that grows and evolves over time but that offers the potential of enhanced satisfaction and fulfillment. That’s something to behold – and something even greater to experience.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment