The Whitaker St. Louis International Film Festival recently completed its 2021 edition in its first-ever hybrid format with theatrical and virtual screening options. This flexible approach made it possible for viewers to screen over 90% of its more than 400 feature films and shorts in the traditional manner at multiple locations or from the comfort of their own homes. While some of the virtual presentations were available in Missouri and neighboring Illinois only, many others could be streamed nationwide, making it possible for movie fans to see some excellent films without being in metro St. Louis, an increasingly popular viewing option for many film festivals (and one that I heartily applaud).

Thanks to this format, I was able to screen a great number of films – 23 in all. The festival’s 30th edition had its share of fine offerings (especially in the documentary genre), but there were also some that could have been better. Below are my summary reviews of the releases I watched. Full reviews of select films are to come.

“The Berrigans: Devout and Dangerous” (USA) (5/5)

In times of war and great social challenges, it can be difficult to remain devoted to one’s principles – no matter how strongly we feel about them – when prevailing circumstances threaten to curtail our freedoms and our ability to express our feelings about them. Yet there are courageous, unflappable individuals who refuse to let such conditions stop them, as evidenced by the protests led by activists Philip and Daniel Berrigan and Elizabeth McAllister. In this superb documentary about the lives of these three heroic figures (two priests and a nun who walked their talk when it came to their Catholic values), director Susan Hagedorn chronicles the efforts of these anti-war advocates who destroyed draft records as a means of protesting US involvement in the Vietnam War, along with their activities in the civil rights movement and the early days of the AIDS crisis. They paid dearly for their actions, spending considerable time in prison, but they could not ignore their conscience in carrying out these acts of deliberate defiance. Through a wealth of archive materials and contemporary interviews with family members and those who worked with them (such as actor Martin Sheen and Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg), these three activists brilliantly come to life, both as advocates for their causes and as compassionate, committed individuals, all captured in a highly personal way. This material is supplemented with voiceover narrations of the brothers’ writings read by Liam Neeson and Bill Pullman, adding an intimate and thoughtful dimension to their portrayals. We owe much to these virtuous champions, and this eminently moving film makes that abundantly clear.

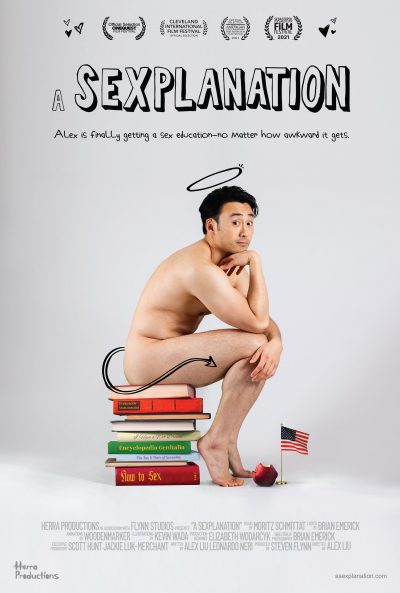

“A Sexplanation” (USA) (5/5)

In a culture so pervasively obsessed with sex as ours, it’s amazing that it’s simultaneously so hung up and ignorant about the subject as well. That’s an intriguing paradox filmmaker Alex Liu wanted to explore. So, at age 36, the gay Asian-American director decided to make a documentary about it, one that he hoped would shed some light on this for society at large, not to mention himself, too. As someone who grew up with a shameful outlook about sex, both in terms of his individual orientation and the subject of eroticism in general, he wanted to get to the bottom of this conundrum, especially in light of his apparently robust libido as an adult. In his singularly humorous deep dive into this matter, he interviews a wide range of experts on sexuality and those who have contributed to shaping our collective views on the subject, including researchers, educators, counselors, scientists and religious figures, as well as family members, friends, and everyday men and women on the street across all ages, ethnicities and sexual preferences. The result is an eye-opening cinematic experience, one that offers significant insights and enlightened solutions for addressing willful bashfulness and broad-based ignorance, all served up in a delightfully whimsical, frequently hilarious offering punctuated with clever animation and frank though lighthearted conversations. The filmmaker’s debut feature is a real treat that leaves little to the imagination while pointedly but tactfully informing audiences of all ages on so many different fronts.

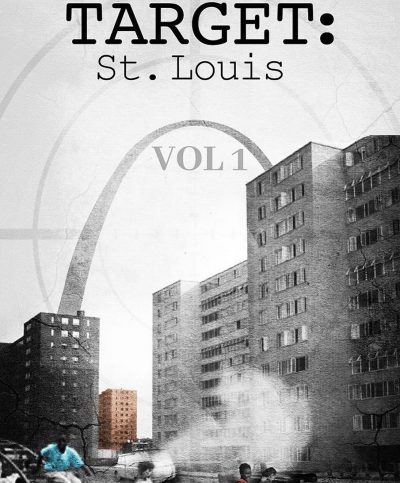

“Target: St. Louis Vol. 1” (USA) (5/5)

If watching this damning indictment of reprehensible clandestine activities by the US government in the 1950s and ’60s doesn’t leave you thoroughly appalled, you must not have a conscience, a soul or a shred of humanity in your being. Director Damien D. Smith’s debut documentary feature tells the story of how the US military, in conjunction with various defense contractors, intentionally exposed residents of a predominantly African-American housing project in St. Louis to repeated open air dustings of toxic chemicals to determine what effects the substances would have on them, all without their knowledge or consent. The result was a host of serious illnesses, including rampant forms of cancer, that affected individuals at the time and many years later. What’s worse, because of legal technicalities, victims were effectively unable to sue any of the parties involved. Through interviews with survivors of the testing, as well as researchers and advocates working to bring the truth to light, the filmmaker has produced a shocking release that is bound to leave viewers incensed about what transpired – especially when it’s revealed that this sort of deplorable Third Reich-style form of experimentation may be only one such example of what our government had done (or could still be doing) without telling us. This is a powerful wake-up call, folks.

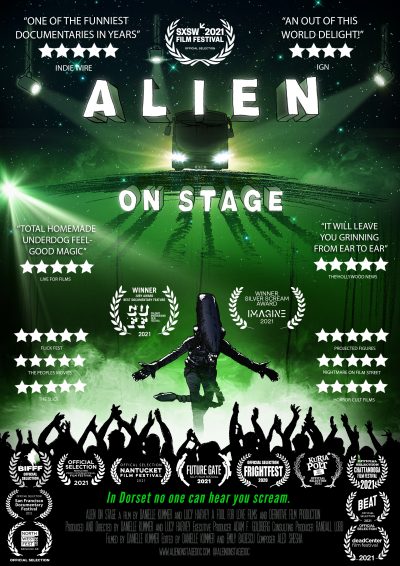

“Alien on Stage” (UK) (4/5)

When an amateur British theater company decides to do something different for its annual holiday charity production, the crew goes out on a limb to stage a work that’s truly out of this world – a theatrical adaptation of Ridley Scott’s sci-fi cinematic classic, “Alien.” As audacious as this undertaking might be, however, the play’s initial run in the company’s hometown of Dorset is a flop. But, when the show catches the attention of documentary directors Lucy Harvey and Danielle Kummer, the company’s fates change dramatically. The filmmakers help the amateur troupe secure an opportunity to stage a performance of the play in London’s West End – and to a sold-out crowd at that. Thus begins this chronicle of an unlikely production brought to life both on stage and in this hilariously offbeat documentary. While the film could use a little more background about the principal players, this wickedly funny saga about a horror classic transformed into a campy romp provides meticulous behind-the-scenes detail, intercut with footage from the film original to provide context and comparison. Most of all, though, this is a fitting tribute to all the underdogs out there who are willing to stick their necks out and attempt the untried, all the while having fun and ultimately attaining unexpected yet much deserved success.

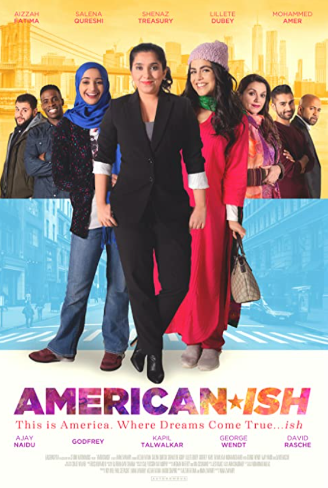

“Americanish” (USA) (4/5)

Though somewhat uneven, sometimes predictable and occasionally formulaic, this otherwise-delightful rom-com about the budding love lives of two Pakistani-American sisters (Aizzah Fatima, Salena Qureshi) and their immigrant cousin (Shenaz Treasury), along with the intrusive meddling of their overbearing mother/aunt (Lillete Dubey), pleases on virtually all counts. This charming debut feature from writer-director Iman K. Zawahry explores the triumphs and challenges of balancing career, impending marriage, entrenched tradition and evolving values, and it does so with insight, candor and gentle humor, successfully fusing the traditional romance and cross-cultural assimilation genres. Watch for more from this filmmaker given the great start she has had with this release.

“Delicate State” (USA) (4/5)

Imagine if you were parents-to-be, blissfully happy about the impending blessed event, when suddenly a devastating civil war breaks out. That’s what happens to a young middle class couple living in an unidentified American city as they await the birth of their first child, all the details of which are meticulously recorded in a video diary filmed during the increasingly troubled pregnancy. After a somewhat slow and slightly unfocused start, writer-actor-director Paula Rhodes’s debut feature soon changes lanes and tells a chilling story that grows ever-more compelling as it unfolds, leaving viewers on edge as they witness developments taking place in a simulated real-time context. The picture brings an added touch of realism to the narrative as it was filmed during the actor-director’s own pregnancy, accompanied by real-life husband Charlie Bodin as the protagonist’s co-star. The result is a startlingly eclectic mix of unnerving terror and relentless hope fused into one story with an all-too-familiar sociopolitical backdrop. Handily, this is one of the most unusual releases I’ve seen in some time, yet it offers us a potent cautionary tale that we had better take seriously if we expect our society to survive – or otherwise run the risk of lawless, uncontrolled collapse.

“A Matter of Perspective” (“Eine Sache der Perspektive”) (Austria) (4/5)

How we perceive the nature of a particular situation ultimately depends on the perspective we each hold about it, even when those outlooks don’t agree with one another. But how can that be if the scenario is fundamentally “the same” for all concerned? That’s where the fallacy of this notion becomes apparent, and director Gerda Leopold’s second feature does a fine job of illustrating this through a collection of interwoven stories (mostly of romantic and relationship matters) involving 10 characters whose paths cross in myriad synchronistic ways. What’s most intriguing about these interactions, however, is how diversely the various participants in these scenarios view their circumstances compared to one another, despite their mutual involvement in them. Ironically, one of the film’s greatest strengths is its reluctance to provide definitive resolution to many of the narrative’s incidents, reinforcing the notion that, given differing perspectives, there often is no set answer that applies across the board. Admittedly there are some elements of this Austrian production that seem to be somewhat truncated, but that’s a small price to pay for an otherwise-engaging film, one that features a fine ensemble cast and some inventive camera work, with cinematography aptly befitting the picture’s subject matter. A delicious indie gem.

“My So-Called Selfish Life” (USA) (4/5)

A woman’s life isn’t complete until she has a child and becomes a mother, right? Well, that may be the traditional view, but, is it still true today? And, for those who have opted to go the childless route, why is there such a strong backlash against their decision? Don’t they, as adults, have the right to make up their own minds? In light of this, director Therese Schechter, who has intentionally chosen to forego motherhood, decided to make a documentary on the subject, examining all of the implications involved, including those of a cultural, personal, familial, vocational and lifestyle nature. Through interviews with physicians, sociologists, researchers, advocates and women who have purposely chosen to go childless, intercut with clever animation and clips from movies and TV, the filmmaker presents an insightful look at the options today’s women have – choices that previous generations largely lacked, an outlook that enabled the prevailing view about motherhood to become so firmly entrenched. While this offering may ruffle some feathers among traditionalists, the film nevertheless gives a big, polite middle finger to those who try to dictate terms to women based on arguments that amount to little more than “Because I said so.” A real eye-opener, especially for those who continue to believe they have no choice in the matter.

“Soy Cubana” (Cuba/USA) (4/5)

How frustrating it must be to have talent – and a tremendous gift to give the world – only to be thwarted by bureaucratic red tape and needless, outdated government restrictions. So it has been for many Cuban artists looking to showcase their talents abroad. Fortunately, though, there have been some lucky breakthroughs, such as those that occurred during a narrow window from 2015 to 2017, when cultural exchange relations between the US and Cuba were briefly relaxed, enabling artists like the Vocal Vidas – a Cuban a capella quartet – to slip through a visitation window that allowed the talented foursome to give three performances in Los Angeles. The process was not an easy one to negotiate, as the window of opportunity was in the process of closing, but the Vidas were able to pass through in time, to the benefit of everyone who saw them perform live and to those viewing this documentary about their storied odyssey. Directors Ivaylo Getov and Jeremy Ungar have assembled a delightful chronicle of their journey, including footage of their performances, as well as the complex process of securing visitation visas to perform in the US. The film features ample footage of their singing, both in the US and Cuba, as well as insights into their respective lives, both as performers and as individuals struggling to get by in the fiscally strapped island nation. A truly delightful, uplifting, inspiring watch.

“Voodoo Macbeth” (USA) (4/5)

When the Roosevelt Administration launched the Federal Theatre Project in 1935 as part of the government-sponsored New Deal program, that initiative included a Negro Unit specifically aimed at developing African-American theatrical productions. One of that unit’s most auspicious undertakings was the staging of an all-Black cast adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, set in Haiti instead of Scotland. To get this version of the play into production, unit heads Rose McClendon (Inger Tudor) and John Houseman (Daniel Kuhlman) hired a 20-year-old neophyte director named Orson Welles (Jewell Wilson Bridges) to bring it to life. Welles had a bold vision for this Harlem-based production, but he encountered endless challenges in making it happen, including multiple casting issues, funding obstacles initiated by a Congressman (Hunter Bodine) who claimed the play was “Communist propaganda” and the director’s own obsessive, self-destructive behavior. Nevertheless, the cast and crew soldiered on, despite these obstacles, to put their own spin on this classic tale. This docudrama, a project of the USC School of Cinematic Arts, was written by a team of eight students and shot by a crew of 10 top graduate students, a collaboration that has resulted in a fine finished product. Some of the writing is a bit over the top at times, and some of the acting is admittedly rather hammy (and not in the Shakespearean sequences, where one would most likely expect it), but the casting overall is quite solid, as are the period piece production values. It’s gratifying to see a student project turn out as polished as this one has, making it a film that deservedly warrants a general release to reach a wider audience.

“Archipelago” (“Archipel”) (Canada) (3/5)

This experimental animated film offering from director Félix Dufour-Laperrière is indeed difficult to categorize. On one hand, it feels like a cinematic meditation, a poetic visual tone poem. On the other hand, it comes across like a metaphysical, metaphorical, surrealistic travelogue to the islands of Quebec’s St. Lawrence River, attempting to draw connections between what has arisen there and those who created it – us. While the visuals certainly work beautifully, the narrative is often scattered, appearing more than a little disjointed and wonky as the film’s river journey to the ocean progresses. Kudos are definitely in order for the French Canadian filmmaker’s attempt at something different here, but there is something to be said for invoking restraint over unrestricted free rein, as is more than apparent in the finished product. It’s an ambitious effort that is likely to leave viewers visually dazzled but somewhat perplexed, as every review I have read of this film has interpreted it differently (and often at wide variance from one another). Make of it what you will.

“Atlas” (Switzerland/Belgium/Italy) (3/5)

In filmmaking, it’s one thing to build suspense and something else entirely to forestall the obvious and inevitable. Unfortunately, in director Niccolò Castelli’s second feature, he seems to believe that he’s doing the former when, in fact, the film is more rooted in the latter. This fact-based story about a young Swiss woman (Matilda De Angelis) who loses three close friends (including her partner (Nicola Perot)) in a terrorist bombing in a popular Moroccan café while they’re on a trip to climb the nation’s legendary Atlas Mountains chronicles her efforts to recover from the incident, both physically and emotionally. As noble and inspiring as that may be, however, the overlong preamble leading up to the film’s depiction of that event – covering almost two-thirds of the movie – is needlessly stretched out, stringing along viewers toward something that they know is coming but that continually seems to get put off. The sought-after suspense just isn’t there, because everyone essentially knows what’s coming beforehand. While the film successfully makes observant statements about Western society’s pervasive fear of potentially traumatic events, as well as the inherent paranoia that often accompanies interaction with those of different ethnic and religious backgrounds, its primary narrative thread about the protagonist’s recovery could have been handled better on more than a few occasions, especially in the picture’s protracted and overly cryptic opening segment. A well-intentioned but mishandled attempt at telling a story that could have been far more compelling if treated differently.

“Confetti” (USA) (3/5); Rotten Tomatoes (***)

As noble and uplifting as this family drama is, especially in its depiction of a concerned parent willing to do anything to help her child, the film is a little too rote all around to make it engaging and affecting. Writer-director Ann Hu’s third feature addresses the issue of dyslexia and what a loving mother (Zhu Zhu) puts herself through to aid her daughter (Harmonie He), a victim of an inadequate, unenlightened Chinese education system, to help her get the assistance she needs to overcome her learning disability. With the assistance of an American teacher (George C. Tronsrue) on an educational exchange program, mother and child subsequently relocate to New York to get that help, aided by one the educator’s friends (Amy Irving), an assertive, disabled writer who takes them in. Once there, the narrative faithfully follows the tried-and-true formula of what’s involved in realizing that objective, touching on each required development in precise, perfectly timed order. While the film may indeed be informative about its subject matter, its predictable presentation format could have just as easily been used to address almost any other health-related, psychological or social issue; simply plug in the right pieces to achieve the desired result. Ironically, though, there are also some crucial story elements that are all too easily glossed over, making one wonder how these significant developments occur with surprisingly remarkable ease. Then there’s the casting, which could use some shoring up, too; while Zhu and He are fine, the supporting performances leave much to be desired, particularly those turned in by Irving and Helen Slater as a special school administrator, both of whom could have easily phoned in their portrayals. Clearly, this is a picture with its heart and intentions in the right place, but its execution needs more spit, polish and imagination to draw audiences in and keep them suitably riveted.

“The Kinloch Doc” (USA) (3/5)

The City of Kinloch, Missouri, located just east of the St. Louis airport, is the oldest incorporated African-American community west of the Mississippi River. Yet, because of deliberate political maneuverings, the city has slowly been eaten up by dubious governmental initiatives, forcing many residents out and leaving only a small remaining population, placing the municipality’s very existence in jeopardy. Director Alana Marie’s chronicle of a city of hard-working, family-oriented individuals that has been systematically torn apart by manipulative forces in the name of progress and serving the greater good reveals a frightening and nefarious pattern that has happened in minority-dominated communities in other parts of the US, one in which residents have been taken advantage of on multiple fronts. However, as effective as the film is at documenting these issues, the overall project feels a little thin and somewhat incomplete, mainly due to only scant inclusion of material on why residents have such beloved feelings for their community. Given the film’s mere 50-minute runtime, there is certainly room for more information about the people of Kinloch and not just the problems they have had to endure, details that would have certainly amplified the nature of the injustices being perpetrated here and made the story more personal in the process. As it stands, this documentary feels like a first cut that could benefit from some supplementation and reworking to strengthen the arguments behind what happened to Kinloch and why such practices should cease, both there and in other at-risk communities around the country, while reminding viewers that this is a story about people and not just property.

“The Lonely Man” (China) (3/5)

Retirement can be a frightening prospect for many individuals, especially those who have occupied their jobs for a long time and aren’t sure what they’ll do with themselves when such familiarity is absent from their lives. So it is for a gas station manager in a remote Chinese province who serves his community by doing more than just pumping petrol. Can he bear the idea of giving up the sense of impassioned, personalized responsibility that he has cultivated with his constituency over the past 20 years? And what of the young apprentice successor he’s training – can he adequately follow in his predecessor’s footsteps? Those are the questions raised in director Han Wanfeng’s touching comedy-drama about life in the snowy frontier at the base of Tianshan Mountain in China’s Kazakh region. As delightful and heartfelt as the film often is, however, it’s somewhat episodic and predictable at times, along with some elements that seem odd and out of place, such as a Bollywood-inspired musical number featuring a colorful performance of a Kazakh folk song. There is also an issue with the subtitling, which is quite small, full of typos and frequently moves by at a rapid-fire pace. Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings, this gorgeously filmed offering is generally enjoyable, the kind of picture that will definitely tug at the heartstrings and bring more than a few smiles to one’s face.

“Solutions” (Denmark) (3/5)

Coming up with viable solutions to the world’s many ills these days is by no means easy. There are myriad problems, and they’re often interrelated in ways that are difficult to identify, diagnose, quantify and resolve. Issues related to the environment, economics, democracy, inequality, communication and a host of other matters are difficult to address because of this intrinsic interconnectedness. So what do we do? In the days before the pandemic, a 10-day conference was organized involving 20 high-level experts in these and other fields. They met in New Mexico to discuss potential solutions, and this gathering provided the basis of the latest documentary project from Danish filmmaker Pernille Rose Grønkjær. The result is an engaging collection of recorded segments from the group’s sessions, as well as clips from interviews with individual participants, each examining the greatest challenges we face and proposing potential solutions. The film itself is well-organized and clearly defines the issues, providing concise summaries of how we might address them. However, as much as I enjoyed the presentations here, I was somewhat underwhelmed by the content itself. Many of the proposals come across as well thought out but overly intellectualized – Ivory Tower propositions that may well be needed but seem unlikely of ever being implemented for one very basic reason: they do not take adequate account of the impact of the current state of human nature. To believe that everyday citizens of the earth will simply agree with these lofty, principled ideas because experts tell them they should seems wholly naïve, even if they have the potential to rectify things. Without a corresponding change in human nature, no amount of intellectualism – no matter how seemingly well-reasoned – is going to get us out of the mess we’re in now. And, unfortunately, the film may offer good ideas but false hopes for getting the job done at a point in our history where time may be running out.

“A World for Julius” (“Un mundo para Julius”) (Peru/Argentina/Spain) (3/5)

Picture yourself as a young boy from an affluent family in Lima, Peru in the 1950s. You live in a grand mansion with multiple servants in the lap of luxury. You’re an inquisitive, observant, sensitive child, but there’s much around you in your family and society at large that you don’t understand. Much of it doesn’t make sense to you, either, such as racism, sexism, abuses of power, bullying, discrimination, class prejudice, and, of course, death. Why, you wonder, do these things exist? That’s the challenge for a five-year-old (Rodrigo Barba) growing up in a world of privilege that often leaves him sad and lonely, especially when it comes to most of the family members who ignore him. In fact, the servants are about his only friends, people he adores and who return the favor in kind. Based on the 1970 novel of the same name by Alfredo Bryce Echenique, a work considered one of the most significant works of Latin American literature, director Rossana Diaz Costa’s made-for-TV movie does a generally fine job of capturing the angst of its young protagonist, despite the fact that it tends to lose its way in the final act, especially at the very end. However, in the first two-thirds of the film, don’t be surprised if it tugs at the old heartstrings and maybe even brings a well-earned tear or two to your eye. The filmmaker’s second feature is by no means a bad film, though, with some shoring up in the home stretch, it definitely could have been better.

“The Teacher” (“Muallim”) (Turkey) (2/5)

When a member of the early 20th Century political reform group Young Turks returns home to the Ottoman Empire after earning his engineering degree in Paris, his political views get him exiled by the government to a small town in Anatolia to teach school to the destitute community’s children. While there, the teacher sees firsthand why he’s fighting for reform, but he’s frustrated at every turn, with his freedom (and even his life) put in jeopardy whenever he seeks to champion his ideals and the well-being of the uneducated and exploited townsfolk. As inspiring as this fact-driven story might seem, however, the film suffers from a woefully unfocused screenplay, with a narrative that continually jumps around without serious development and punctuated by some of the corniest dialogue I’ve seen in a movie in years. Director Muslim Sahin appears to have all the makings of a good movie here, but the finished product is so far off the mark that one can’t help but wonder where it’s headed virtually from start to finish.

“We Burn Like This” (USA) (2/5)

The issues of anti-Semitism and Neo-Nazism, regrettably. are still alive and well, and they even show their faces in some unlikely locations, such as Montana’s Big Sky Country. Director Alana Waksman’s debut feature deals with this very subject and from a perspective based on actual incidents. The film follows the story of Rae (Madeleine Coghlan), a young Jewish woman living in Billings whose grandparents survived the Holocaust. However, much to her dismay, she’s now being targeted for harassment by hate groups, sending her into a downward spiral of depression and substance abuse. She finds herself living the religious persecution of her forbears, and she’s not entirely sure what to do about it. After a hospital stay for an overdose and an ongoing inability to resolve her circumstances, Rae pays a visit to her mother (Kendra Mylnechuk) in Butte, where she learns of and recalls other painful memories from her past, forcing her to either take control of her life or be consumed by it. Unfortunately, the film has trouble pulling all of this together to make for a coherent and compelling picture. The narrative often feels scattered, jumping around at random and skimping in terms of back story along the way. It’s too bad, given that it seems like there’s a good movie in there somewhere; it just never seems to surface.

“The White Fortress” (“Tabija”) (Bosnia and Herzegovina/Canada) (2/5)

This is one of those movies where viewers wait 90 minutes for something to happen and nothing really does. Director Igor Drljaća’s latest tells the story of two Sarajevo teens (Pavle Cemerikic, Sumeja Dardagan) from different social and economic backgrounds who half-heartedly pursue an unconvincing romantic involvement, one that develops at a snail’s pace between individuals who have virtually nothing in common beyond their ability to stumble through deadpan, understated banter. To the film’s credit, it does a fine job developing the character of the two protagonists, but it doesn’t give them much to do. What’s more, the picture’s attempt at trying to fuse reality with fairytale-like qualities occasionally seems promising, but it, too, often falls short of its potential. The result is a meandering, unfocused tale that always seems to hold out the promise of a payoff, but regrettably it never comes. This one is easily skipped.

“The Insurer” (“L’asseureur”) (Belgium) (1/5)

What an absolute mess of a movie. This Belgian offering from director Antoine vans can’t seem to make up its mind if it wants to be a crime caper, a rom-com, a buddy movie or some fusion of all three genres. But, to make matters worse, it’s peppered with irrelevant asides, implausible plot devices, needlessly hyped electronic graphic highlights that add absolutely nothing to the narrative and some of the worst subtitling work I’ve ever seen in a foreign film. I could go on further about this one, but I frankly don’t see the point since this is not worth wasting one’s time to watch. Quite a disappointment, given that there is a lot of material here that could easily have been worked up into something fun and entertaining, but that opportunity is lost early on in a film that never manages to recover.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.