“A Sinner in Mecca” (2015, 2020 re-release). Cast: Parvez Sharma. Director: Parvez Sharma. Screenplay: Sajid Akbar, Alison Amron and Parvez Sharma. Web site. Trailer.

When faced with a paradox, it’s easy to lose hope. Circumstances may seem so inextricably entangled that it appears there’s no way to sort matters out. Indeed, it’s the kind of situation where it seems like only divine intervention can help. And it’s that kind of help that’s being sought by a seriously conflicted individual whose hopes, dreams and aspirations are caught up in a conundrum ostensibly incapable of being unraveled, the subject of the recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca.”

After the completion of his controversial debut feature, filmmaker Parvez Sharma became a marked man. In 2008, the gay Islamic director released the documentary “A Jihad for Love,” which detailed the lives and struggles of homosexual Muslims around the globe. His action earned him a fatwa, a religious opinion that condemned him for the crime of apostasy. Even though he was living in the relative safety of New York, this proclamation hung heavily over him for what was considered such an outwardly blasphemous cinematic statement.

However, this condemnation was not about to stop Sharma from speaking out. He made numerous media appearances to discuss his film and draw attention to the plight of gay Muslims, who often face persecution and severe punishment for their “crimes,” including public beheadings in countries like Saudi Arabia, homeland of the faith. This ascent of his public profile made his personal security even more perilous, a problem potentially complicated further when he married his partner, Dan, when same-sex marriage became legal in the US. But this was not to be the end of his exploits in pushing the envelope.

Even though Sharma could be openly comfortable about his sexuality in his secular life in the US, he faced considerable challenges when trying to be himself in a religious context. And faith was not something that the filmmaker took casually. Having been born and raised in India, he grew up in a rich religious tradition, devoutly practicing his faith and adhering to the loving, accepting traditions at the core of Islam. However, in an age when the faith had been hijacked by fundamentalist extremists who distorted many of the religion’s teachings and imposed vile punishments for infractions, all for their own archaic and misogynist ends, it often caused him and countless other peace-loving Muslims to alter their behavior for fear of dangerous reprisals. Here he was, a 21st Century man attempting to live under the dictates of 700-year-old religious laws and doctrines.

[caption id="attachment_11587" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Gay Islamic filmmaker Parvez Sharma documents his odyssey to Mecca, Saudi Arabia for his sacred hajj pilgrimage, a journey all Muslims are required to make at least once in their lifetimes, as depicted in the recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca.” Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Gay Islamic filmmaker Parvez Sharma documents his odyssey to Mecca, Saudi Arabia for his sacred hajj pilgrimage, a journey all Muslims are required to make at least once in their lifetimes, as depicted in the recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca.” Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

This placed Sharma in the middle of a confounding paradox: How could he be both an open and authentically gay man while also being a devout Muslim under the prevailing threatening conditions? This was particularly true for his desire to participate in the hajj, a pilgrimage to the Islamic holy city of Mecca, a venture all Muslims are required to complete at least once during their lifetimes. It was something he was anxious to undertake, but how welcome would an openly gay man with a fatwa on his head be made to feel in journeying to Saudi Arabia’s most sacred site?

This was not the only challenge Sharma faced in making his pilgrimage. As a filmmaker, he wanted to document his odyssey, particularly since it would give him an opportunity to share images of Mecca with the outside world. He believed this was important to provide outsiders with a view of Islam’s holiest site, as well as the devotion of pilgrims who make the journey there, especially since non-Muslims are strictly forbidden from visiting the holy city. However, filming of any kind is illegal in Saudi Arabia, so, in attempting to document his journey, Sharma would be taking on an additional risk besides the fatwa already dogging him.

But perhaps the biggest challenge Sharma faced was the one with himself, wrestling with an uneasy conscience seeking to reconcile his innate sexuality with the tenets of the faith he so dearly loved. How could he be a good Muslim if he were living life in a way that inherently went against its principles and traditions? Could he truly be accepted by his Islamic peers for who he was? But, most importantly, would Allah willingly embrace him as one of the faithful if he were violating what he believed to be God’s will? Indeed, could a sacred pilgrimage really answer those questions for him and provide him with inner peace?

[caption id="attachment_11588" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Devoted Muslims making the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia are required to visit the sacred Kabaa shrine at the holy city’s Great Mosque, a ritual gesture depicted in the recently re-released documentary “A Sinner in Mecca,” available for online streaming. Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Devoted Muslims making the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia are required to visit the sacred Kabaa shrine at the holy city’s Great Mosque, a ritual gesture depicted in the recently re-released documentary “A Sinner in Mecca,” available for online streaming. Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Such are the conditions under which Sharma launched into his journey. With one eye perpetually looking over his shoulder, he embarked on his hajj to complete its various required rituals, armed with only an iPhone camera and two other miniature recording devices to capture events as they unfolded. He wasn’t sure what awaited him, but he was certainly hopeful to find the answers he sought.

What Sharma found surprised even him. He found a world to which the faithful from all over the globe devotedly flocked. He found a sense of devotion that was profoundly moving, including for himself. And he witnessed images of a religious following that flew squarely in the face of what much of the outside world saw as being representative of contemporary Islam. He was especially moved by the throngs of pilgrims piously encircling the Kabaa, the massive cube-shaped shrine at the center of the Great Mosque of Mecca and a symbol that has become virtually synonymous with the hajj.

At the same time, though, Sharma also came upon a world he didn’t expect. Given that millions of visitors descend upon Mecca every year, he found elements that surprised and even saddened him – unbridled commercialism, uncontrolled public sanitation issues, insufficient resources for handling the crowds and militarized security to keep pilgrims in check. Was such greed and squalor something that Islam should tolerate in connection with its most sacred rituals? Were the faithful indeed to go without the provision of basic needs? And were gun-toting guards really necessary to shepherd pilgrims through the various aspects of their odyssey? Such elements ran counter to the Islam that Sharma grew up with, leaving him with a sense of disillusionment, despite the obvious need for instituting such substantial logistical requirements for managing crowds of this size.

[caption id="attachment_11589" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Pilgrims from various Islamic sects around the world make their way to Mecca, Saudi Arabia for the hajj, a ritual of faith all Muslims are required to complete at least once in their lifetimes, as chronicled in “A Sinner in Mecca.” Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Pilgrims from various Islamic sects around the world make their way to Mecca, Saudi Arabia for the hajj, a ritual of faith all Muslims are required to complete at least once in their lifetimes, as chronicled in “A Sinner in Mecca.” Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

In light of the questions that Sharma had going in to this undertaking, as well as the new ones raised by his journey, he seems to have emerged from the experience with more queries on his plate than what he started with. And sorting them out sufficiently appears to have become even more difficult than expected. So where does one go from here? That depends to a great degree on one’s beliefs and how they’re employed through the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in shaping the reality we experience.

It’s unclear whether Sharma has ever heard of or had any experience with conscious creation. However, given that his quandary rests squarely with sorting out his beliefs and what he wants to do with them, his resolution to his issues also seems to depend on the process that makes use of those very same resources in creating something workable from them. So, in light of that, the answers to the many looming questions here would seem to rely on getting one’s belief house in order.

Considering the foregoing, as illustrated in the film, Sharma would appear to have his work cut out for him. To begin with, there’s the fundamental core matter of reconciling his gay life with his religious calling. In accepting his sexuality, he has embraced a significant aspect of his authentic self, despite whatever opposition others may have to his choice to do so. But, in terms of allowing this decision to jibe with his religious self, he’s faced with a bigger question to address: Can he realistically buy into a belief that asks him to willingly deny an integral part of himself in order to be accepted as a proper follower of the religion in which he seeks to participate? The answer to that question would still appear to be in the process of emerging, something that Sharma hoped the hajj would help him determine. How much closer he is to an actual answer by journey’s end, however, is unclear at best.

[caption id="attachment_11590" align="aligncenter" width="350"] The hajj pilgrimage is a moving moment of faith for all Muslims as seen in director Parvez Sharma’s recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca.” Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

The hajj pilgrimage is a moving moment of faith for all Muslims as seen in director Parvez Sharma’s recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca.” Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Then there are the disillusionment beliefs that arose as a result of his pilgrimage, particularly those associated with how well the faith treats its own when making their sacred journey. For instance, Sharma seems to take issue with one of the world’s largest and most lavish shopping malls being located only a stone’s throw away from the Great Mosque of Mecca. Indeed, the very notion of this calls to mind the story of Jesus and the money changers in the temple. Is such close proximity to a sacred site really appropriate for a Starbuck’s? And what does that say about the character of one’s faith – is a religion that sanctions such practices truly worthy of one’s devotion? Has it lost sight of the principles upon which it was founded in favor of secularized, self-serving interests?

Then there are the larger issues of the faith – is it acceptable to throw one’s support behind a religion that has been hijacked by extremists and has willingly cast aside its humanitarianism, leaving the world with a distorted view of what it’s all about at its heart? As a religion claimed by one-sixth of the world’s population, is it acceptable to allow it to be mischaracterized in such a distorted way? Can beliefs along those lines be justified?

These are some of the pressing matters to be resolved, and Sharma, like many others in his shoes, is up against a difficult stack of beliefs to sort out. To that end, though, he proposes a significant idea to consider – that contemporary gay Muslims become involved in bringing the faith into the 21st Century, helping to institute change to a religion that in many ways is still stuck in the 1400s. That’s certainly a noble and pragmatic idea, but, to make it happen, one must invoke beliefs aimed at realizing that outcome. Given that conscious creation makes anything possible, it’s an idea certainly worthy of consideration. But, if it’s going to happen, one must first believe in the possibility, because, after all, that’s what conscious creation is all about.

[caption id="attachment_11591" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Encircling the Kabaa shrine at the Great Mosque of Mecca is an event virtually synonymous with the Islamic hajj pilgrimage, as seen in the recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca,” available for online streaming. Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Encircling the Kabaa shrine at the Great Mosque of Mecca is an event virtually synonymous with the Islamic hajj pilgrimage, as seen in the recently re-released documentary, “A Sinner in Mecca,” available for online streaming. Photo courtesy of Haram Films.[/caption]

Back in time for Pride month via online streaming, this highly personal 2015 documentary about a gay Muslim examines the quandary of an individual seeking to be true to himself on diametrically opposed fronts. Questions of attempts at fulfilling sanctioned elements of devotion clash with personal values that run counter to them, pitting the protagonist against himself as he seeks to reconcile feelings for which there are no easy answers. As someone who risks the death penalty for his lifestyle, as well as legal sanctions for engaging in artistic pursuits that are forbidden in Islam’s homeland, director Sharma takes viewers on a journey that captivates, educates and boggles the mind, all at the same time. There are moments when Sharma’s story will leave viewers shaking their heads, as well as occasions when the material seems padded and somewhat self-indulgent. However, if nothing else, this offering will leave audiences with myriad questions about how to sort out personally significant but inherently conflicting circumstances, some of which may be applicable to our own circumstances, whether we’re Muslim or not.

It’s been said that he who tries to serve two masters will be torn asunder. And, when dealing with circumstances whose qualities are worlds apart, that just may be true unless an obviously inventive solution can be found. Thankfully, though, that’s one of the beauties of beliefs; they can be tailored to specifically suit our needs, enabling the most wondrous creations. All we need do is come up with the right combination of attributes to fulfill our requirements and then commit to seeing them realized. The result just may feel heaven sent.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Tuesday, June 30, 2020

‘A Sinner in Mecca’ seeks to unravel an entangled paradox

Thursday, June 25, 2020

‘Miss Juneteenth’ cautions us on the dangers of stalemates

“Miss Juneteenth” (2020). Cast: Nicole Beharie, Alexis Chikaeze, Kendrick Sampson, Lori Hayes, Marcus M. Mauldin, Akron Watson, Liz Mikel, Phyllis Cicero, Lisha Hackney, Mathew Greer, Jaime Matthis, Margaret Sanchez. Director: Channing Godfrey Peoples. Screenplay: Channing Godfrey Peoples. Web site. Trailer.

Being stuck in our circumstances can be a horrible fate. Such stalemates keep us mired in unsatisfying conditions, preventing us from moving forward. But what’s even worse is not realizing that we are stuck, an exercise in ongoing frustration examined in the new generational drama, “Miss Juneteenth.”

In 2004, Turquoise Jones (Nicole Beharie) was proudly crowned Miss Juneteenth, the top honor in a beauty pageant staged in honor of the 1865 freeing of the remaining Black slaves in Texas, two years after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Turquoise was thrilled by her victory; in addition to the notoriety that came with the title, she received a full scholarship to a traditionally Southern Black university of her choice. She sincerely believed that this achievement was the start of a bright future, full of promise and accomplishment.

Fifteen years later, however, life has turned out to be very different from what Turquoise expected. As the single mother of a free-spirited teenager, Kai (Alexis Chikaeze), the daughter of a fundamentalist Christian but alcoholic mother, Charlotte (Lori Hayes), the separated wife of an unreliable husband, Ronnie (Kendrick Sampson), and the manager of a popular but rundown Ft. Worth barbecue joint, she has her hands full. She struggles to hold things together but somehow manages to get by. But, as pressures mount, will she be able to continue doing so?

Turquoise’s biggest concern is Kai. She wants her daughter to have a better life than she has had. And, to make that possible, she’s convinced it can happen by Kai following in her footsteps as the next Miss Juneteenth. She scrimps to save up the funds needed to cover the pageant entry fee and to pay for a beautiful gown (ironically, a lovely shade of turquoise). She also works hard at helping Kai develop the poise and qualities needed to become a successful contestant. There’s just one catch – Kai doesn’t really want it.

Considering everything that Turquoise is doing for her, Kai might be looked on by some as an ungrateful brat. But is she? It’s obvious she’s quite gifted as a dancer known for provocative steps and equally enticing costuming, but is she really cut out for the comparatively tame acts typical of a beauty pageant contestant? That’s apparent as she struggles to recite the Maya Angelou poetry that her mother insists she present in the pageant’s talent competition; it’s just not her style. What’s more, Turquoise is concerned that Kai isn’t making an effort to portray herself with expected retiring and demure attitude of a beauty queen. Turquoise suggests that Kai may be hanging around with bad influences, including a would-be boyfriend (Jaime Matthis) and even her own father, afraid that such associations could leave the wrong impression with onlookers who see Kai out in public and thereby jeopardize her chances of winning.

Thus begins an ongoing struggle between mother and daughter. Kai has dreams of her own and wants to be able to be herself in fulfilling them. Turquoise, meanwhile, may be well-meaning when it comes to her daughter’s welfare, but is she truly looking out after Kai’s best interests or trying to make up for her own failings related to an opportunity that didn’t pan out as anticipated? It’s one thing to have hopes for one’s child, but it’s something else entirely to be an all-encompassing control freak. After all, Turquoise, of all people, should be cognizant of that in light of her own mother’s incessant attempts at trying to coerce her into joining her church. Can’t she see the parallels?

With these conditions in place, the stage is set for a showdown between what mom wants and what her 15-year-old daughter is prepared to do. Will there be joy and celebration? Or will there be despair and disappointment? Or is it possible that something else entirely may emerge? Await the envelope to see what wins the day.

It’s indeed unfortunate that circumstances haven’t turned out for Turquoise as hoped for. But, to a certain degree, one can’t also help but ask, “Who’s fault is that?” She’s apparently an intelligent and resourceful woman, but she’s made what some would consider questionable choices along the way, and those decisions have left her to deal with the consequences. She’s not happy with what she’s been saddled with, but that doesn’t mean she’s reconciled to those conditions for the rest of her life. So what is she to do about them?

Much depends on what Turquoise believes about herself – who she is, what she’s capable of and what she would like to do. And the beliefs underlying those matters are crucial, for they will determine what results. This is the essence of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents in manifesting the reality we each experience.

If Turquoise genuinely hopes to rise to the excellence she believes she’s capable of, she’s got her work cut out for her when it comes to assessing her abilities, commitments and objectives, as well as the beliefs underlying them. How she sees herself is important, because it will determine which thoughts, beliefs and intents she embraces. And, on this front, she needs to take a critical look at where she stands.

Obviously, Turquoise is holding on to hope from the past that failed to materialize. It has kept her stuck in place for 15 years. And now she’s seeking to impose this same thinking on someone else who isn’t burdened by such notions – Kai. Turquoise is hoping to get a second shot at the brass ring vicariously, transferring her aspirations onto a daughter whose own dreams are different from those of her mother. And, given the desperation Turquoise feels, the more aggressively she seeks to impose her aims on Kai, who’s anxious to strike out in her own direction, regardless of what her mother wants.

Clearly, Turquoise is holding on to beliefs and sought-after outcomes that no longer serve her. This is true not only where the pageant is concerned, but also in her relationships with Ronnie, Charlotte and even Wayman (Marcus M. Mauldin), owner of the barbecue joint. She readily slips into the role of caretaker in each of these cases, dutifully trying to help them out with their shortcomings, just like a good little beauty queen contestant should. But, if Turquoise sincerely wants to help herself move forward, she must realize what she’s doing and cut these ties, changing her manifesting beliefs accordingly.

In their own way, Kai, Wayman, Ronnie and Charlotte are all attempting to point Turquoise in this direction. Kai is determinedly seeking to reach out and follow her own dreams, providing an example for her mother to follow; Wayman flat out tells his manager that the restaurant is his, that he owns it free and clear, and that he’ll run it the way he wants; and Ronnie and Charlotte each make promises they can’t keep and behave unacceptably in various ways, purposely trying to drive wedges between them and Turquoise to implicitly encourage her to let go of them and their issues, problems that only they can solve. The question is, of course, “Is Turquoise paying attention?”

In addition to realizing the inherent pitfalls in these situations, Turquoise must accept responsibility for her actions (or inactions). Again, others (most notably Kai and Wayman) are attempting to set examples for her. They’re accountable for their choices and what results from them, for better or worse. But what matters most is that these are their choices and that they’re being responsible for them. If Turquoise were wise, she’d follow suit.

Should Turquoise choose to follow this path, opportunities await. For example, in addition to working as the restaurant manager, Turquoise is a part-time cosmetician for a funeral home owned by her friend Bacon (Akron Watson), someone who’s interested in her for more than just her makeup application abilities. As his business is expanding, Turquoise faces the prospect of a full-time job. And, as circumstances go south in her relationship with Ronnie, a willing, successful and responsible suitor waits in the wings.

So why isn’t Turquoise jumping at these opportunities? That’s on her. As someone who’s struggling to discover her authentic self and the beliefs that shape it, she hasn’t fully realized what’s on offer. To a great degree, she must give herself permission to avail herself of them, but, given where her mindset is at, she’s not ready to do so until she lets go of the belief flotsam that’s obscuring her view. Whether or not she takes this step depends on her ability to discern her circumstances and take advantage of what’s been presented to her. For her sake, we can only hope she does.

There’s a tremendous irony in all this, too. After 15 years, Turquoise is still hung up on the pageant and her failure to capitalize on its promise, a preoccupation that has, in many ways, kept her trapped in her past. Yet the Miss Juneteenth competition was established to celebrate emancipation, and Turquoise’s personal liberation has been thwarted by her own stalled fixation. Some might argue that this isn’t entirely surprising, considering that beauty pageants themselves could be viewed as anachronisms that hold women back, keeping them corralled into lifestyles and modes of behavior that are anything but liberating, another irony in light of the historical event that this pageant was created to celebrate. Given the nature of these competitions, perhaps it would benefit not only Turquoise, but also all other potential contestants, to eschew the assumed “value” of events like this, opting instead to explore possibilities that applaud the independence and empowerment of women. Now there’s something worth celebrating.

“Miss Juneteenth” lovingly tells a bittersweet tale about expectations that don’t pan out as hoped for but that can still work out in the end, provided we don’t become locked into inflexible, obsessive thought patterns. This touching and complicated story about trying to live one’s dreams – or to compensate for our failures by living them out through others – features excellent performances by Beharie and Chikaeze (in her big screen acting premiere), as well as a smartly written, though occasionally predictable screenplay. Director Channing Godfrey Peoples’s feature film debut marks the appearance of a promising new talent, serving up an entertaining and heartwarming tale that breaks many molds, delivers a wealth of surprises and offers viewers much to ponder. The film is available for first-run online streaming.

Wallowing in wishful thinking and thoughts of “what might have been” may provide us temporary shelter from the storms of our psyche when we’re not ready to address what’s troubling us. But taking up permanent residence there can cause considerable long-term harm to our personal growth and development, especially if we aspire to the greatness we know we’re capable of. Taking stock of who we are and what we want, as well as the attendant responsibility, can help promote the forward progress that gets us moving again. And, if we stick to our convictions, that just may lead to crowning achievements beyond our wildest dreams.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Monday, June 22, 2020

Thoughts on the Moment

Recent events on both a national and global scale have given me pause to reflect on where we are and where we might be going. There are no easy answers, and opinions likely vary widely, depending on one’s own particular circumstances. As a consequence, this time in history could turn out to be a great tragedy – or a tremendous opportunity. This question is, “Which will we choose?”

While pondering these matters, it dawned on me that I addressed this subject several years ago in the Epilogue to my most recent book, Third Real: Conscious Creation Goes Back to the Movies. At the time, events were well on the path to spinning out of control, but circumstances were nothing like they are at the moment. What I wrote at the time was based on speculation, hunches and a prediction for what could happen – and what might result from it if we didn’t heed the warning signs and take them seriously in mapping out what kind of future would result from them. I also explained how the contents of that book could potentially play into the ideas covered in the Epilogue.

Upon re-reading the Epilogue text one recent afternoon, I realized how much of what I wrote three years ago is relevant to our current conditions. So, in light of that, I decided to republish this excerpt from Third Real in the hope that it may provide some insights to those who don’t know what to make of our present circumstances – and what to do about them as we move forward into an immensely uncertain future.

While the main thrust of my writing is about movies, my Epilogue observations only deal with them tangentially. The Epilogue has more to do with conscious creation – the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents – and what we should do with this practice. As I have noted in all three of my books, movies provide us with examples we can draw from in shaping our beliefs, but, in this Epilogue, unlike the main text of my titles, I make only passing references to specific films. For detailed illustrations, read the main text of my books, since here I’m choosing to focus on the principles underlying them – and how we might draw upon those concepts in moving forward. Goodness knows, with what’s happening these days, I can’t think of a better time to do that – in earnest and, preferably, as soon as possible.

With that said, here is the Epilogue to Third Real, edited minimally [in brackets] to provide context for present conditions and to incorporate elaboration and clarification not contained in the original. End notes have been retained for attribution and additional clarity where needed.

I hope you find my words from the past useful in the thoughts of today.

Epilogue

Time To Get Real

Toward the Creation of a New Paradigm

“Forward movement is not helpful if what is needed is a change of direction.” ―Dr. David Fleming1

For quite some time now, political, business and social activist leaders have been saying that we need to fix our world, that we need to set things on a path that moves us forward. But, truthfully, as noble as those sentiments may be, what have such statements actually gotten us? As I write this [in 2017], we’re in a world beset by a host of issues that, if anything, only seem to be getting worse, not better.

As a general rule, I like to think of myself as an optimist, believing in the hope of a better future. With infinite probabilities and the limitless potential of conscious creation at our disposal, I’d like to think that we can collectively manifest great things. Indeed, as [author and conscious creation advocate] Jane Roberts wrote in Seth Speaks, once we realize that we create reality with the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents, we’re no longer enslaved to events and circumstances, that we can birth an existence that we want.2 And, through it all, I’ve always contended that we can draw inspiration from the arts, particularly film, to help show us the way to achieve that goal.

I touched on these points in the Epilogues of this book’s two predecessors. In Get the Picture?!, I wrote of the endless possibilities conscious creation enables and how we can look at movies as examples of how to realize them.3 And then, in Consciously Created Cinema, I picked up on that notion and suggested that we apply it to improving the prevailing circumstances of our world.4 But, given how drastically and dramatically events have unfolded (dare I say deteriorated) in recent years, I feel as though my words may not have been emphatic enough. In light of that, then, let me put it this way: I believe it’s time we get real about putting conscious creation to use to bring a new paradigm into being.

I have addressed this idea through a number of the film summaries in [Third Real]. Virtually all of the entries in Chapters 7 and 8, for example, present cautionary tales that deal with issues great and small that merit attention from all of us. But simply showing concern or paying lip service may no longer be enough. Conditions, I believe, have reached a point where we earnestly need to put our beliefs and deeds into action to address these matters before they get away from us. As observed in [Jane Roberts’s] The “Unknown” Reality, Volume 1, “If some changes are not made, the race as such will not endure.”5

Now do you see what I mean about getting real? [As discussed in this book’s Introduction,] I’m convinced that we’re truly on the verge of our own third reel/third real moment, and we’d better get busy before it escapes us and the credits start to roll.

So how, exactly, do we go about this? First and foremost, we must wake up and understand how our world comes into existence and from whence it originates. Then we must put those methods into practice, with clarity of thought, open-mindedness and carefully crafted manifesting beliefs. However, as this Epilogue’s opening quote suggests, this may call for a revolutionary new way of thinking, one that’s not focused just on fixing what we have, but of striking out in an entirely new direction. Of course, to do that, we must also deconstruct what’s in place, particularly ridding ourselves of beliefs that no longer serve us. For instance, as Jane Roberts wrote in The Individual and the Nature of Mass Events, if we cling to notions like “you can’t change human nature” or adhere to beliefs that “man’s nature is to be greedy, a predator, a murderer at heart,” we’re unlikely to advance ourselves into a new world.6 Instead, we’ll remain mired in circumstances that grow progressively unbearable as we continue to materialize a reality based on such unsavory core assumptions.

Given that, it would seem it’s time to change our tune and to employ the means and methods designed to realize an outcome in harmony with that new melody. In addition to drawing upon the conscious creation basics outlined in Get the Picture?! and Consciously Created Cinema, we can also tap into the ideas covered in [Third Real] to manifest a radically new reality. The concepts and themes of the chapters chosen for Third Real were carefully selected to get us past some of the pitfalls that can derail or impinge upon our materialization efforts. They’re all designed to provide us with greater precision in our conscious creation practices, a new and enhanced degree of aptitude intended to not only move us forward, but also to shepherd us in a new direction.

It’s especially worth noting that this is something we need to do collectively, the point behind the inclusion of Chapter 10, [concerning co-creation,] in this work. We need to get past the idea that we’re separate and apart from one another, instead embracing our acknowledgment that we’re all in this together, innately connected and part of a greater integrated whole. Thus, if we’re truly inescapably linked to one another, then we all need to participate in the unfolding of this scenario (and, one would hope, in a way that leads to its advancement). And the more of us who realize this, the better off we’ll be. Jane Roberts foresaw this in The Individual and the Nature of Mass Events, in which she wrote that we’re on the verge of creating an improved mass reality, one with fewer frightened people, fewer fanatics and a mindset geared toward birthing an idealized existence.7 Should we succeed at this, we raise the possibility of “enrich[ing] the race, and bring[ing] it to levels of spiritual and psychic fulfillment.”8 That’s quite a destiny – so why not make it our value fulfillment, [the subject of this book’s Chapter 11,] as well?

When we imagine the possibilities, we conceivably have much to look forward to. But, if it’s to occur, it’s clearly up to us. We must be willing to allow it and then to make it happen. Indeed, as many who have had various paranormal experiences have been told, “A new world awaits you if you can take it.”9

Are we up to that challenge? I’d like to think we are. I know I am. So, if this is something we’d like to bring into being, I once again propose the kind of metaphysical call to arms that I raised in the conclusion of Consciously Created Cinema.10 As we load our own third reel onto the metaphysical projector of life, let’s get busy – and work together toward that happy ending all of us want.

End Notes: Epilogue | Time To Get Real

1http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/paradigm-shift. Environmentalist Dr. David Fleming (1940-2010) was the author of Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It (2011).

2 Jane Roberts, Seth Speaks: The Eternal Validity of the Soul (San Rafael, CA: Amber-Allen Publishing/New World Library, 1994), p. 412 (ESP Class Session, January 5, 1971).

3 See Get the Picture?!: Conscious Creation Goes to the Movies, second edition (2014), pp. 363-365.

4 See Consciously Created Cinema: The Movie Lover’s Guide to the Law of Attraction (2014), pp. 275-276.

5 Jane Roberts, The “Unknown” Reality: A Seth Book, Volume One (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1977), pp. 114-115 (Seth Session 687, March 4, 1974, emphasis in original).

6 Jane Roberts, The Individual and the Nature of Mass Events (San Rafael, CA: Amber-Allen Publishing, 1995), p. 259 (Seth Session 862, June 25, 1979).

7Id.

8 Jane Roberts, The “Unknown” Reality: A Seth Book, Volume One (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1977), pp. 114-115 (Seth Session 687, March 4, 1974).

9 This has largely occurred with those who have had UFO encounters, though it has also come up in other paranormal contexts, such as in channeling sessions not unlike those that Jane Roberts experienced in her contact with her noncorporeal writing partner, Seth.

10 See Consciously Created Cinema: The Movie Lover’s Guide to the Law of Attraction (2014), pp. 275-276.

Copyright © 2017-18, 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved

Thursday, June 18, 2020

This Week in Movies with Meaning

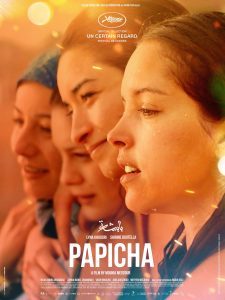

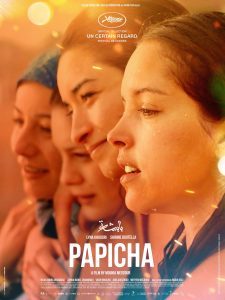

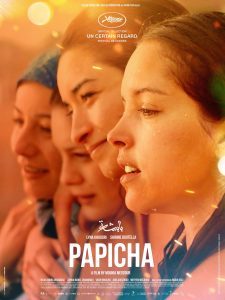

Reviews of "Papicha," "The New Bauhaus" and "Spider" are all in the latest Movies with Meaning post on the web site of The Good Media Network, available by clicking here.

Wednesday, June 17, 2020

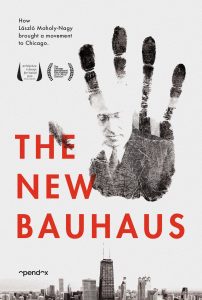

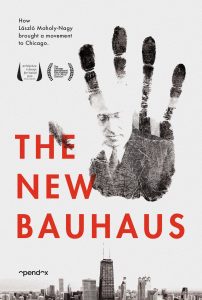

‘The New Bauhaus’ dissects the creative process

“The New Bauhaus” (2019 production, 2020 release). Cast: Interviews: Elizabeth Siegel, Joyce Tsai, Robin Schuldenfrei, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Hattula Moholy-Nagy. Archive Material: László Moholy-Nagy, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius. Director: Alysa Nahmias. Screenplay: Alysa Nahmias and Miranda Yousef. Web site. Trailer.

A Chinese fortune cookie I once cracked open imparted a simple but inspiring message, “There is no greater joy than creation.” Those words have stayed with me for years, and I’m always moved when I see comparable sentiments expressed through other means. And, in that vein, a recently released film echoes that notion through a portrait of an individual whose calling epitomizes that very idea, the central figure profiled in the engaging new documentary, “The New Bauhaus,” available for first-run online streaming.

László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) isn’t exactly a household name, though there are many who contend that it should be. As one of the most influential yet least known figures in 20th Century art and design, Moholy-Nagy’s imprint can be found in a wide array of artworks, as well as the design of many everyday consumer goods. That’s quite a range for any one person, but not all of these creations come directly from his hand; many are the creations of the students he taught and the peers he influenced over the years. Yet the inspiration, in either case, stems from a brilliant, if underappreciated visionary who accomplished more individually in his scant 51 years than groups of collaboratives produce in their entire lifetimes.

Born in Hungary in 1895 to a largely dysfunctional family, the young László was shuttled off to be raised by extended relatives. Given these conditions, he quickly learned how to look after himself, taking the initiative to attend to his own needs. By his late teens he moved to Budapest and then Berlin, becoming involved in a variety of cutting-edge technology and modern art ventures. He developed a reputation for his innovative works, and, in 1923, was invited to join the faculty of the Bauhaus, a German art and architecture institute known for its leading-edge work. It was quite a coup for a bright young mind full of ideas who had no formal training.

With the rise of the Nazi party, however, conditions changed radically. The Reich’s disapproval of modernist artworks – what came to be known as “degenerate art” – made it difficult for Moholy-Nagy and his peers to get their work into circulation, let alone accepted. What’s more, new laws were enacted restricting the employment of foreigners within Germany, hindering the Hungarian artist to continue working there. He soon left for the Netherlands and then England, though neither location suited him. So, when he had an opportunity to relocate to the U.S. in the 1930s, he jumped at the chance.

Moholy-Nagy landed in the bustling city of Chicago, a metropolis whose freewheeling spirit and boundless energy intrigued him, a perfect fit for an artist seeking to explore his creative leanings and make a name for himself. He found that opportunity in 1937, when the Association of Arts & Industries sought to establish a new school based on the Bauhaus model, and the organization reached out to Moholy-Nagy to head up the venture. Before long, the New Bauhaus was born.

In launching this effort, Moholy-Nagy had an ambitious agenda in mind. He sought to create an educational environment that went beyond mere vocational training in design. Instead, Moholy-Nagy envisioned an institution where students could learn the mechanics of creativity, becoming immersed in discovering how to fuse art, design and technology in new and creative ways. The intent was to go beyond just coming up with finished products; it was about learning how raw materials could be fashioned in ways that revealed their innate properties, especially discovering qualities and attributes that may never have been dreamed of before, all in the hope of developing goods that were both aesthetically pleasing and successfully fulfilled practical objectives that made life better, easier and more enjoyable for their end users.

Moholy-Nagy’s experiment may have been noble, but it was something of a flop. Many of the students didn’t grasp what the founder was striving for. And the school’s backers were disappointed that this new venture wasn’t yielding the kinds of outcomes they sought. After a year, the New Bauhaus was history, and Moholy-Nagy was looking for his next opportunity.

With the generous backing of Chicago-based Container Corporation of America, a company known for its support of the arts both in its advertising and corporate culture, Moholy-Nagy subsequently launched his own institution, the School of Design in Chicago (later renamed the Institute of Design) in 1939. Given such a sympathetic sponsor to bankroll his efforts, Moholy-Nagy was free to pursue the establishment of the kind of school he wanted to create. And, this time, the students took to it with tremendous optimism, joy and enthusiasm. They relished the creative freedom this environment afforded, and they happily went about their pursuits, no matter how demanding the work may have been.

Moholy-Nagy became a celebrity of sorts through this enterprise, his school often attracting noted artists who made appearances as guest lecturers and faculty, frequently taking no fees for their contributions. One of the most noteworthy was visionary Buckminster Fuller, who spoke before rapt audiences of design students eager to soak up whatever wisdom and insights he had to offer.

Continuing the approach he used at the New Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy encouraged his students to find their own creative voices. He wanted them to understand the rudimentary aspects of design and material qualities and how they could be transformed into art, regardless of the finished product in question. In essence, this provided students with a creative template or framework from which to operate, showing them that their approach to their efforts was ultimately more important than what resulted from it.

Nonetheless, truly inventive creations came out of these hypothetical endeavors, items that may not have been envisioned were it not for the innovative approach employed in coming up with them. For instance, this approach led to artistically appealing yet practical applications in the area of product design ergonomics. The Dove soap bar, with its distinctive curved shape that perfectly fits both a soap dish and a user’s palm, is a prime example of a consumer good that employed this design technique and became a best seller in the process. The same is true of the whimsical and wildly popular bear-shaped honey dispensers that can be found on many American breakfast tables. And then there’s the clam shell-shaped telephone, which didn’t catch on at the time it was designed but subsequently inspired the look of many handsets to come along in later years.

Moholy-Nagy’s influence touched the works of artists in many other areas, too. For example, he inspired many graphic artists, such as those who went on to design the initial issues of Playboy magazine, the psychedelic advertising materials used by 7 Up in the 1960s and album covers for the Rolling Stones. He even had an impact on those in the movie industry, including the designer of the inventive cinematic montages featured in the opening credits of the James Bond films.

Perhaps one of Moholy-Nagy’s greatest accomplishments was changing how we view photography. At the time he worked with it, photography was seen as a technology, nothing more. However, by employing it in new and different ways, he transformed it into a serious art form, a designation it previously hadn’t enjoyed. Today we take such a notion for granted, but, were it not for Moholy-Nagy’s efforts, that outcome may have never resulted. But then that was typical of how he approached his craft, looking for ways to fuse elements and disciplines in ways that hadn’t been attempted before – and forever changing our world, our perceptions and our art in the process.

Sadly, Moholy-Nagy died of leukemia at age 51 in 1946. Some would say he left us far too soon, but, as his daughter Hattula observes in the film, he produced a wealth of material in an array of milieus during the time he was here. The impact he had on the art world, both seriously and commercially, went underappreciated for decades, but, thanks to recent museum exhibitions and this film, his contributions are finally beginning to receive their just due.

What’s arguably even more important, though, are the insights he imparted about the creative process and how it can be applied to so many assorted endeavors, including those that go beyond what we typically associate with the concept of art. Moholy-Nagy placed as much value on the means and methods by which we create as on what results from them, an idea that was revolutionary for the time (and not always readily accepted). Nevertheless, he firmly believed in what he was doing and drew upon those notions in manifesting his works, products of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we tap into these resources for materializing our existence. And what a reality he created, one that keeps on manifesting today, years after his death.

Even if Moholy-Nagy never heard of this philosophy, he clearly had a good handle on its principles. A big part of his success is attributable to his focus on beliefs related to the inherent means for bringing all this about. In many instances, we tend to place so much emphasis on the end result that we lose sight of how we get there. Yet the process is what makes the outcome possible, so, if we hope to arrive where we want to be, we should give due consideration to the journey and not just the destination, for the trip will determine the form we end up with.

The beliefs that go into the creative process not only show us the direction to take, but they may also help us to imbue the outcome with qualities that we might not have otherwise envisioned. Moholy-Nagy believed that what we create should both fulfill the sought-after needs and provide end users with attributes that make their lives more useful and satisfying. Those aspects of a creation may not be apparent at the outset, but they could well emerge as the design process unfolds, revealing themselves as the manifestation gradually comes into being. Indeed, if one were to wonder how a proverbial better mousetrap might arise, this approach to building it would likely reveal how.

This approach proved valuable to Moholy-Nagy not only in devising his finished works, but also in terms of how he ran his school. For example, during World War II, when finances and materials became more scarce, he had to get creative to come up with new ways to acquire both in adequate supplies. Where money was concerned, for instance, he attracted funding by introducing curricula with practical applications, such as camouflage design. He sought to recruit students (and their tuition money), along with additional funding support, to investigate the means for projects like hiding large buildings and even concealing the entire Chicago lakefront. On the materials side, with metal hard to come by because of the war effort, he looked at alternate resources to work with. Consequently, he and his students began experimenting with wood in ways never thought of, such as using it to provide the support mechanisms in bedding.

To succeed at envelope-pushing endeavors like this, we need to push past the limitations in our beliefs that hold us back. This is positively essential for projects where creativity is a core element of the undertaking, because standard approaches aren’t likely to yield anything new, different or innovative. Fortunately, limitations don’t even appear to have been part of Moholy-Nagy’s thinking; he stridently forged ahead, apparently not giving a second thought to the restraints of convention. And, for both his benefit (and ours), it’s good that they weren’t part of his process; we can only guess what imaginative manifestations would be missing from our reality today if it had been otherwise.

Thankfully, this approach to the creative process appears to have been part of Moholy-Nagy’s value fulfillment, the conscious creation principle associated with being our best, truest selves for the betterment of our being and that of others. His influence was (and still is) far-reaching, resulting in many creative finished works to be enjoyed, both aesthetically and commercially, as well as inspiring the output of generations of fellow kindred spirits who have since walked in his footsteps. That’s quite a legacy, one whose impact continues to unfold to this day and is likely to continue doing so on into the future.

“The New Bauhaus” is a fitting cinematic tribute to an underrated artist and his work, featuring plenty of examples of his art and that of those he influenced. The film’s extensive archive material shows rare footage of Europe in the days before his immigration, as well as ample still photos from the subject’s time at the New Bauhaus and the School of Design. A wealth of expert commentary is provided by Moholy-Nagy’s daughter, Hattula, along with observations from educators, art curators, historians and former students. Aspects of the protagonist’s life chronology could be a little better organized, but the overall portrait painted here provides an in-depth look at the life of someone influential but largely unknown.

As the experience of Moholy-Nagy and his followers illustrates, there is tremendous power and joy in acts of creation. They can take a plethora of forms, too, unfathomably greater than even the phenomenally prolific output of the New Bauhaus and School of Design students and faculty. That in itself should be good cause for the optimism, joy and enthusiasm that came to characterize the attitudes of those enrolled in these remarkable institutions, serving as an uplifting example to the rest of us as we undertake all of our creative endeavors, whether we’re attempting something as ambitious as painting a mural – or simply cooking dinner.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Tuesday, June 16, 2020

‘Balloon’ examines the beauty, and difficulty, of choice

“Balloon” (“Qi Qui”) (2019). Cast: Jinpa, Sonan Wangmo, Yangshik Tso, Druklha Darja, Palden Nyima, Konchok, Kunda. Director: Pema Tseden. Screenplay: Pema Tseden. Web site. Trailer.

We all value having choices in our lives, especially when they offer us a variety of pleasant outcomes. But what happens when we’re presented with options that seemingly hold no appeal, regardless of what we choose? We may feel like we have our backs up against the wall, unable to decide what to do. However, through it all, we must never lose sight of the fact that our power of choice is always with us, a paradox examined in the new Chinese cinematic fable, “Balloon” (“Qi Qui”).

In 1979, the People’s Republic of China adopted a stringent one-child policy to help control its exploding population, a social experiment that remained in place for the next 35 years (a program detailed in the excellent documentary “One Child Nation” (2019)). When the policy was implemented, families that had more than one child were allowed to stay intact, but, with very few exceptions, they were not permitted to have any more offspring. Unintended pregnancies were generally terminated through abortions followed by sterilizations. So, to help avoid such incidents, the government launched an aggressive birth control campaign through the distribution of free condoms. Unfortunately, those prophylactic items were sometimes in short supply, especially in remote areas, where they came to be treated as valuable commodities not to be squandered. And, for the Tibetan family depicted in this film, the availability of those precious contraceptives goes a long way in determining their fate.

At a time when family size is being curtailed by government mandate, Dargye (Jinpa) and his wife, Drolkar (Sonan Wangmo), are blessed to be the parents of three sons, one an adolescent away at school and two youngsters (Druklha Darja, Palden Nyima) still living at home. The children were born prior to the policy going into effect, so the family was allowed to stay together although prohibited from any more new arrivals. But mom, dad and the kids are not the only ones at home. Sharing the house with them is Dargye’s elderly father (Konchok), who helps take care of his grandsons. Their life as sheep herders in a desolate territory isn’t always easy, but this family of devout Buddhists pulls together when needed, reverently placing trust in their faith to endure whatever challenges befall them.

However, with Grandpa getting on in years, his attentiveness in caring for the little ones sometimes comes up short, and their mischievous ways land them in trouble. While rummaging through the house, the youngsters come across the last of their parents’ condoms, and they proceed to inflate them, thinking they’re balloons. Needless to say, Dargye is furious when he finds out, upset that his boys would invade their parents’ privacy as they did and then subsequently ruin what remained of mom and dad’s stash of sacred treasure. And, to make matters worse, when Drolkar visits the local health clinic to obtain more condoms, she learns that its supply is depleted. That makes things difficult for her when she returns home, where she must contend with a perpetually oversexed husband, one whose libido is about as strong as that of the rams in his flock.

[caption id="attachment_11550" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Tibetan sheep herder Dargye (Jinpa, right) and his elderly father (Konchok, second from tight) look upon disapprovingly when Dargye’s two mischievous young sons (Druklha Darja, Palden Nyima, left) inflate condoms, thinking they’re balloons, in director Pema Tseden’s new cinematic fable, “Balloon” (“Qi Qui”). Photo courtesy of Rediance.[/caption]

Tibetan sheep herder Dargye (Jinpa, right) and his elderly father (Konchok, second from tight) look upon disapprovingly when Dargye’s two mischievous young sons (Druklha Darja, Palden Nyima, left) inflate condoms, thinking they’re balloons, in director Pema Tseden’s new cinematic fable, “Balloon” (“Qi Qui”). Photo courtesy of Rediance.[/caption]

Drolkar’s circumstances become further complicated when her sister, Shangchu Drolma (Yangshik Tso), comes for a visit. Shangchu, a woman with a murky past that’s never fully explained, apparently sought sanctuary for whatever “indiscretions” she may have committed by becoming a Buddhist nun. But what should be a happy reunion is disrupted when Shangchu has a chance encounter with the young man (Kunda) who apparently was the source of her disgrace, reminding her of her past and making her visit to her sister a trying time, adding to the tension that already exists at home.

As time passes, Dargye grows ever more “anxious” that his needs aren’t being met. Drolkar wants to have her tubes tied to solve the contraceptive issue for good, but her husband can’t wait for that, coaxing her into reluctantly having sex without protection. One can only imagine what the result of that is.

Not long thereafter, tragedy strikes with Grandpa’s passing. The family dutifully follows the Buddhist death rituals, giving the patriarch a proper send-off into the afterlife. But no sooner does this happen when the family learns from religious leaders that Grandpa’s spirit is already prepared to reincarnate, making his return in the newborn growing and developing in Drolkar’s womb.

Dargye insists that the spirit of his deceased father be allowed to be reborn, but Drolkar fears what consequences await her if she carries a fourth child to term. Suddenly husband and wife are caught between the dictates of the state and the tenets of faith, a dilemma that not only pits powerful principles against one another, but that also strains the relations of a longtime loving couple. Who and what will win out? That’s what remains to be seen as this mystical and political morality play runs its course.

The story in “Balloon” is, in many ways, something straight out of Aesop, a fable riddled with irony and myriad questions in need of being answered. Principal among them, of course, is, what is one to believe about all this? That may seem simple and straightforward enough, but the answer to that question is important, for those beliefs will play a crucial role in what transpires, as they provide the basis of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon those intangible resources in manifesting the reality we each experience.

As practitioners of this philosophy are well aware, when it comes to our manifesting beliefs, we get what we concentrate upon. So, if we have multiple materializations that we’re seeking to bring into being, the ones to which we give priority are those that are most likely to appear. However, for that to happen, we must first sort out which manifestations we deem most important and focus our efforts accordingly. And, when it comes to determining the precedence of the issues facing this family, there is much to be considered, especially the order of importance.

[caption id="attachment_11551" align="aligncenter" width="275"] Tibetan sheep herder Dargye (Jinpa) makes a purchase at a local market to show his two young sons the difference between condoms and balloons in the new cinematic fable, “Balloon” (“Qi Qui”). Photo courtesy of Rediance.[/caption]

Tibetan sheep herder Dargye (Jinpa) makes a purchase at a local market to show his two young sons the difference between condoms and balloons in the new cinematic fable, “Balloon” (“Qi Qui”). Photo courtesy of Rediance.[/caption]

Decisions in this regard draw heavily from our innate power of choice. It’s something that’s always with us, even when it may not seem that way, such as when we need to decide about seemingly no-win situations. And, as this story plays out, there are numerous choice points along the way that determine our beliefs and what subsequently occurs. For example, the boys’ decision to inflate the last-remaining condoms creates the circumstances affecting their parents’ strained sex life. In turn, Dargye and Drolkar’s choice to have unprotected sex leads to the unwanted pregnancy. And that, of course, raises the matter about whether to have or abort a baby that likely contains the reincarnated spirit of Dargye’s deceased father.

At each of the junctures along the way, belief-based choices are made that lead to the resulting circumstances that follow, and, in each case, the stakes are upped when it comes to the decisions about what follows next. The seemingly mischievous acts of two little boys ultimately prove to have tremendous consequences, all of which illustrates the inherent power in our choices, our beliefs and what stems from them. Acts of creation are indeed formidable matters, regardless of how trivial or inconsequential they might initially appear.

This thus raises the question, are there any tools that we can draw upon in helping us to make decisions in situations like this? That’s a tricky one to answer, given that conscious creation essentially makes all outcomes possible. What we choose depends on a variety of factors, such as which life lessons we wish to experience, what manifestations are most likely to align with our authentic selves and core beliefs, and whether others are providing input into acts of co-creation (and how relevant that input is). Conceivably, that leaves us with much to consider, a palette of variables that can lead to a wide array of outcomes – and carry a host of consequences.

As noted above, the ante in this scenario is continually raised at each choice point. Which is why it is so critical for the participants in this story to choose wisely, doing whatever they can to consider what might result. Envisioning possibilities plays an important role in this, for it can provide us with a glimpse of what could lie ahead. And we can enhance our ability to do this by carefully examining the input that goes into our beliefs and decision-making processes. Most notably, this involves giving due regard to the primary sources of that input, our intellect and intuition. They can help to guide us in what we decide and what we believe and, by extension, what we create.

For Dargye and Drolkar, they face difficult choices about how to proceed. They must draw upon all of their metaphysical resources in determining what to do. It’s a situation in which they must look to both their consciousness and their conscience in setting their belief priorities, for what they choose will have tremendous impact with staggering ramifications. Many of us probably wouldn’t envy them for what they’re up against, but, then, most of us have likely been in comparable tight spots of our own where we were pressed with difficult choices. If so, let us hope we made the right decisions. And, if not, then we should pay attention to the experience of this couple in their ruminations about how to proceed.

The principal choice in this story – whether to adhere to the will of the state or the power of our hearts – is about as difficult a decision as any that any of us would ever have to make. Many of us might see this as a case where either choice would ultimately be unacceptable: Terminating a pregnancy to comply with the law but killing a reincarnated spirit in the process or carrying the child to term to fulfill a spiritual purpose while risking criminal sanctions and the likely murder of the baby upon birth. There may be no good outcome from either decision, but, if nothing else, such a scenario reminds us of an important truth – that we all have the power of choice at our disposal at all times and that it’s something we always need to cherish, no matter what circumstances we’re up against.

Not to be confused with the German film of the same name, “Balloon” is a paradoxical fable about what happens when spiritual beliefs collide with sociopolitical public policy. Poetically told by director Pema Tseden, with inventive and often-breathtaking cinematography, an ethereal score, and a sensitive storytelling approach, this simple but stirring tale moves viewers in heartfelt ways at both ends of the emotional scale. While the pacing is a tad sluggish in the middle (especially where Shangchu’s story is concerned), that shortcoming is easily overlooked in light of everything else this excellent film has to offer. This winner of the 2019 Chicago International Film Festival award for best screenplay has primarily been playing the festival circuit thus far, but it appears to be getting ready for general release, at least in some overseas markets. Its future for a domestic release is unclear, but, should it become available, it is well worth a look, the kind of genuinely touching tale that doesn’t make it into distribution nearly often enough.

When faced with hard choices, we may feel like there’s no way out of such difficult circumstances. However, when we make a decision to proceed, we also often find that a great weight is lifted, providing us with a tremendous sense of liberation, one that leaves us feeling renewed and perhaps even touched in an unexpectedly profound way. When that happens, we may forget all about the turmoil we went through in reaching that point – and be forever thankful that we had our power of choice to help us get there.

Copyright © 2019-20, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Making a Statement on The Cinema Scribe

Tune in for the latest Cinema Scribe segment on Bring Me 2 Life Radio, Tuesday, June 16, at 2 pm ET, available by clicking here. And, if you don't hear it live, catch it later on demand, with new listening options available! In addition to Spreaker, the show is now available on iHeart Radio, Spotify, Podcast Addict and Podchaser!

Saturday, June 13, 2020

‘Spider’ spins a troubling web of truth

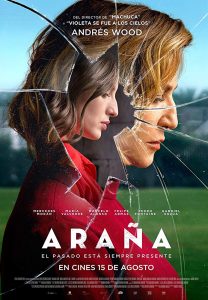

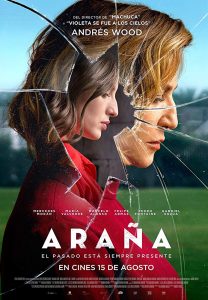

“Spider” (“Araña”) (2019). Cast: María Valverde, Mercedes Morán, Gabriel Urzúa, Felipe Armas, Pedro Fontaine, Marcelo Alonso, María Gracia Omegna, Mario Horton. Director: Andrés Wood. Screenplay: Guillermo Calderón. Web site. Trailer.

Truth can be a powerful weapon, one that can both avenge wrongs and operate as a force of devastating destruction, sometimes simultaneously. The power associated with it can have tremendous ramifications and in a variety of contexts. And, when evidence of truth in both its aspects surfaces, the implications can be staggering. So it is for three individuals whose stories are rooted in the past and thought forgotten until they’re unexpectedly revived in the present, an intense saga depicted in the taut Chilean political thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”).

In 1970, socialist Salvador Allende (1908-1973) became president of Chile, the first Marxist ever democratically elected to a nation’s top office in Latin America, an outcome widely greeted with much popular fanfare. However, not everyone was pleased with the result, most notably right-wing conservatives who opposed the new president’s proposed reforms, some of which included the nationalization of certain industries. Those who stood to lose from such changes organized formal opposition groups, most notably the radical Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party. The organization’s aggressive and sometimes-brutal tactics included everything from assaulting leftists in street brawls to formally planning Allende’s ouster (a result that eventually came to pass in a 1973 coup). The FLNP also became somewhat infamous for its distinctive logo, a series of interlocked lines meant to represent the chains of Marxism arranged in a pattern that resembled a spider (as depicted in the accompanying photos).

The FLNP’s membership primarily consisted of upper and middle class college students, and the story in this film follows the exploits of three of them – Inés (María Valverde) and her boyfriend, Justo (Gabriel Urzúa), both of whom recruit a soft-spoken but violent-tempered peer, Gerardo (Pedro Fontaine). The trio is something of an unlikely threesome: Inés, a beauty pageant contestant, and Justo, a product of the Chilean bourgeoisie, are significantly different from Gerardo, a military veteran from a working class background. It’s not clear how solidly Inés and Justo are committed to the cause, but Gerardo is all in, providing their cell with much-needed muscle when called for. Nevertheless, despite their differences, they work together to carry out the organization’s missions and spread its rhetoric.

[caption id="attachment_11540" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Chilean college students Inés (María Valverde, left) and her boyfriend, Justo (Gabriel Urzúa, right), become active proponents of the right-wing conservative Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party in the early 1970s, seeking the ouster of the nation’s democratically elected Marxist president, Salvador Allende, as depicted in director Andrés Wood’s latest offering, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.[/caption]

Chilean college students Inés (María Valverde, left) and her boyfriend, Justo (Gabriel Urzúa, right), become active proponents of the right-wing conservative Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party in the early 1970s, seeking the ouster of the nation’s democratically elected Marxist president, Salvador Allende, as depicted in director Andrés Wood’s latest offering, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.[/caption]

However, matters grow complicated when Inés starts taking a liking to Gerardo. The passion that swells up between them quickly turns hot and heavy, and their less-than-discreet interactions eventually raise Justo’s suspicions. Consequently, when Justo assigns hazardous tasks to his new recruit, one can’t help but wonder if he’s doing so because he believes Gerardo is the best man for the job or because the dangers involved in these tasks could potentially take him out of the picture – and out of the life of Inés. That notion gets put to the test when the assignment involves a proposed political assassination, an ideal task for a former military man – and one in which having a potential patsy in place could prove valuable to protecting the movement and fulfilling its objectives.

Skip ahead to the present day. An older Inés (Mercedes Morán) is now an influential and successful businesswoman active in Chilean commerce and politics. She’s married to Justo (Felipe Armas), but time has not been kind to him; he’s an alcoholic shadow of his former self, largely withdrawn and much less in the public eye. Their affluence supports them comfortably, but the secret of their FLNP past forever haunts them, threatening to wipe away their prosperity and destroy the illusion of their so-called respectability if the truth were exposed.

The potential for undoing everything gets amped up with the return of their old colleague, Gerardo (Marcelo Alonso). After a disappearance of more than four decades and believed dead, he returns to Santiago, looking very much like a dissheveled hermit. He’s apparently still committed to taking down those he considers “undesirables,” though he’s not pursuing Marxists any more; he has new targets (most notably thugs and immigrants), and he seems set on going after them.

As Gerardo cruises the streets of Santiago’s seedier neighborhoods, he looks on in anguish. He’s disgusted by the seemingly omnipresent criminal element, surveying the landscape like a vigilante in waiting, a latter-day version of Travis Bickle from “Taxi Driver” (1976). And, when he witnesses a street robbery, he pounces, chasing down the perpetrator and killing the criminal with his car in an act of what he sincerely believes to be a justifiable citizen’s arrest. However, once taken into custody, authorities lock him up, especially when they learn that he has a huge stockpile of weapons stashed away.

[caption id="attachment_11541" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Violent-tempered military veteran Gerardo (Pedro Fontaine, left) is recuited to provide muscle for the right-wing conservative Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party in 1970s Chile by college student Inés (María Valverde, right), a relationship that turns romantic as well as political, in director Andrés Wood’s new thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.[/caption]

Violent-tempered military veteran Gerardo (Pedro Fontaine, left) is recuited to provide muscle for the right-wing conservative Fatherland and Liberty Nationalist Party in 1970s Chile by college student Inés (María Valverde, right), a relationship that turns romantic as well as political, in director Andrés Wood’s new thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.[/caption]

When Inés learns of his arrest, she grows concerned and seeks to call in favors to safeguard her security by keeping him in confinement. But, even with that, many questions linger: Why has Gerardo returned? Will he reveal details about his past that will also implicate Inés and Justo? Is he securely detained, unable to escape his incarceration? And what would happen if he somehow managed to get out? Many potential consequences hang in the balance, including Inés’s criminal history, as well as her current reputation, her personal safety and those 40-year-old unresolved romantic leanings.

As the past and present collide, a great deal of long-accumulating dust is about to be stirred up. Truths will be revealed, and the ramifications associated with them will surface in multiple ways. In the end, though, they can’t be escaped – and neither can their implications.

When we’re unable to be truthful about ourselves (or sometimes even with ourselves), we run the risk of spinning a web of deceit, which is why “Spider” is such an aptly fitting title for this film. The protagonists in this story – especially Inés and Justo – have difficulties with this, failings that are apparent both in their past and in their present. In large part, that’s due to their inability to define and understand their authentic selves, an issue that arises from not knowing what to believe about their true nature. And this shortcoming, unfortunately, drives their implementation of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon our beliefs in manifesting the reality we each experience.

For instance, as noted above, when it comes to their commitment to the FLNP, the younger Inés and Justo seem somewhat unclear about exactly why they’re involved. Is it because they truly believe in the right-wing cause? Is it a power and control move? Or is it a byproduct of their backgrounds, protecting the bourgeois lifestyles they grew up with, maintaining the status quo and playing along with their peers for acceptance and popularity? Such personal ambiguity is potentially volatile in light of the risks involved in a scenario like this, something that one should be clear about with oneself before getting in too deep. And this is important not only for them while in their youth, but also down the road in their adulthood, something that their younger selves apparently aren’t thinking much about.

Creating our existence without giving due consideration to the associated consequences can be a time bomb whose detonation can occur at any time, both in the short term and well down the road. And that, for example, is where the danger of recruiting an impressionable Gerardo comes into play. Inés and Justo believe that having a strongman on their team would be advantageous to furthering the FLNP’s actions and objectives, and, from a purely goal-driven standpoint, they’re probably right. However, given Gerardo’s history and behavior, he’s obviously loose cannon, one who can be easily influenced and manipulated, especially when he’s called upon to execute the kinds of high-risk party initiatives that align with his particular point of view. By failing to evaluate the wisdom of their actions and beliefs, Inés and Justo are potentially lighting a fuse that could have explosive outcomes associated with it.

[caption id="attachment_11542" align="aligncenter" width="350"] An elder Inés (Mercedes Morán), a modern-day successful businesswoman, seeks to keep her radical past under wraps in the new political thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.[/caption]

An elder Inés (Mercedes Morán), a modern-day successful businesswoman, seeks to keep her radical past under wraps in the new political thriller, “Spider” (“Araña”). Photo courtesy of Film Factory.[/caption]

Efforts like this are prime examples of un-conscious creation at work, a skewed version of the philosophy whereby desired outcomes are given priority over any potential side effects or fallout that may occur. The roots of this approach are firmly planted in the pasts of the three protagonists, but that doesn’t mean that their misguided schemes will go dormant or evaporate over time. As the seeds germinate, they can come to life as full-blown manifestations, and, for the lead trio in this story, that can have wide-ranging impact on multiple fronts. For Chilean society at large, for example, the efforts and effects of the FLNP can be seen both during its days of active operation and years in the future, results made possible through the overt and covert power amassed by onetime members like Inés and, despite his long absence, Gerardo. Meanwhile, on a personal level, similar ramifications can be seen in the lives of the three former colleagues, most notably their unresolved romantic issues. Indeed, even when we would like to believe that such matters are over and done with, nothing could be further from the truth (there’s that word again).

Under conditions like this, one must often scramble to address undesired outcomes when they arise. The elder Inés, for example, must aggressively call in favors to protect her reputation and personal well-being when she learns that Gerardo may have walked back into her life. Similarly, the elder Justo attempts to deal with his past, both politically and romantically, by escaping into a perpetually inebriated existence to deaden the pain and keep denial at bay. And Gerardo, who no longer has familiar targets to pursue, must come up with new ones to stalk and hunt down to satisfy the drives that have become so ingrained in his beliefs and in the reality he seeks to manifest.