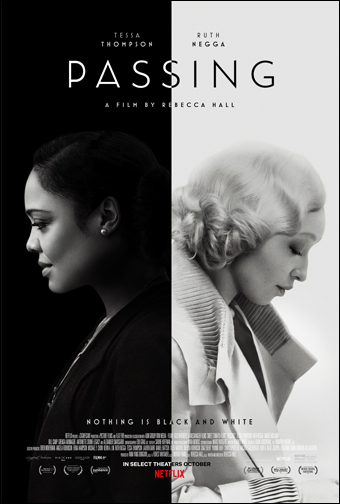

“Passing” (2021). Cast: Tessa Thompson, Ruth Negga, André Holland, Bill Camp, Alexander Skarsgård, Gbenga Akinnagbe, Antoinette Crowe-Legacy, Ashley Ware Jenkins, Justus Davis Graham, Ethan Barrett. Director: Rebecca Hall. Screenplay: Rebecca Hall. Book: Nella Larsen, Passing. Web site. Trailer.

How far would you go to get what you want? In particular, how determined would you to be to fulfill your objectives if you felt you were being intentionally excluded from doing so? The temptation to succeed at any cost under such circumstances might be quite strong, and, if a path were to open up to make things happen seemingly easily, one could be seen as foolish for ignoring such an opportunity. But is that really true? That’s one of many thought-provoking questions raised in the new period piece drama, “Passing.”

In 1920s New York, many have benefitted from the economic boom of the era, but there’s a definite divide along racial lines in terms of how readily that bounty is enjoyed. There are both well-to-do Whites and Blacks, but African-Americans are restricted in terms of how they’re able to participate in celebrating such prosperity. For example, when it comes to living arrangements, Blacks are generally confined to certain designated neighborhoods, such as Harlem. Socially, they’re largely isolated, unable to go many of the places that Caucasians visit freely, limited to their own nightclubs, stores and dining establishments. And interaction between races is virtually unheard of except in extremely constrained, clandestine circumstances.

However, for many African-Americans, those conditions are unacceptable. They want to be able to share in the same pleasures and freedoms as their White counterparts. Some seek to achieve this through activism, often with the support of notable Caucasian backers. But others take a different path, especially those who are light-skinned or of mixed race. By carefully crafting their appearance and mannerisms, they seek to mimic those of the White world, seeking to “pass” for Caucasian, despite the nature of their true ethnic backgrounds. Some become quite good at it, too, so much so that they often blend into White society and no one notices. Obviously, this is not an option for all African-Americans, particularly those with darker skin, but, for those who manage to successfully pull off the deception, they’re able to engage in activities and relationships that many of their peers are unable to do. That is, unless they get caught.

Irene Redfield (Tessa Thompson) is one of those African-American New Yorkers who could “pass” if she chose to do so (and, on occasion, she does so when it suits her, despite the fact that it makes her uncomfortable). Generally, though, Irene prefers to be herself, working with activist organizations to further the causes of her people. Besides, it would be difficult for her to try to pass in most social situations, given that she’s married to a dark-skinned husband, Brian (André Holland), a successful physician, whose ethnicity is more than apparent.

On a hot summer day, while out shopping for her son’s birthday, she stops at the garden tea room of a popular hotel to cool off and refresh herself. While there, Irene has a chance encounter with a childhood friend from the days of their upbringing in Chicago, Clare Bellew (nee Kendry) (Ruth Negga). Irene barely recognizes Clare initially, given how different she looks from when she knew her so many years ago. Her clothes, mannerisms and hairstyle have all changed, but they’ve also been carefully coordinated to allow the light-skinned Clare to successfully pass. In fact, as they talk, Irene learns that Clare has become so adept at passing that she has somehow managed to conceal her true ethnic identity from her wealthy banker husband, John (Alexander Skarsgård), with whom she has given birth to a daughter.

As the conversation progresses, it’s apparent the old friends have much to get caught up on, so Clare invites Irene up to her hotel room to chat further. As it turns out, Clare and John still live in Chicago but are in New York on business, though, given the success of her husband’s career, there is a good possibility the couple may be moving to the Big Apple. Ironically, Clare also shares that John is extremely prejudiced against Blacks, a revelation Irene finds shocking. She wonders how her friend could get away with something so audacious as that. It also makes Irene nervous about being in Clare’s hotel room; after all, what would happen to her and Clare if he were to show up unexpectedly while she was still there?

Which is precisely what happens.

Because of her skin tone, wardrobe and mannerisms, however, Irene is able to successfully pass for John the same way that Clare does. Admittedly, she doesn’t stay much longer, anxious to remove herself from what could potentially become a tense and awkward situation. But, before departing, Clare confides that she would like to see Irene again while she is still in New York.

Once home in Harlem, Irene feels relieved to be back in her element, but she was clearly unnerved by the incident – not only because of the circumstances in which her friend is living, but also because she allowed herself to engage in what she sees as questionable behavior to make the best out of a difficult situation. She keeps the incident to herself and goes about her typical activities, like making arrangements for an upcoming activist function and spending time with Brian and her two sons (Justus Davis Graham, Ethan Barrett). But clearly she has been affected by what happened and tries to figure out how to react to it.

Some time later, Irene receives a letter from Clare, but she ignores it – until one day when she shows up on Irene’s doorstep. Irene reluctantly invites her in, and Clare angrily unloads on her for not responding. As the situation settles down, however, Clare confesses that she’s extremely lonely. Passing may have made it possible for her to avail herself of things that would be otherwise inaccessible, but that practice also fundamentally cut her off from the African-American community, and, now that she no longer has any kindreds of color in her life, she bemoans their absence. She thus saw her chance encounter with Irene as an opportunity to reconnect to her roots. Irene admits that it was good seeing her again, too, but she still has quiet misgivings about how it unfolded.

In the wake of this, Clare begins seeing Irene on a regular basis, though it’s rarely as a result of Irene initiating their meetings. Once Clare meets Brian, for example, he begins extending invitations (not to mention somewhat flirtatious glances), despite his initial decidedly cool reaction to his wife’s friend. Clare also takes a liking to one of Irene’s activist colleagues, famed novelist Hugh Wentworth (Bill Camp), an ardent Caucasian supporter of minority civil rights. She even befriends Irene’s housekeeper, Zulena (Ashley Ware Jenkins), whose polite, deferential demeanor goes through a noticeable change afterward. It’s almost as if Clare is invading Irene’s life and taking it over, but to what end? Is this just the fulfillment of restoring contact with those whom Clare has lost touch? Or is there something more going on? And where is John in all this? He seems to have virtually disappeared, prompting one to wonder how Clare is able to explain all of her mysterious absences without his company.

Through all of these encounters, Irene remains politely reticent despite the fact that her interactions with Clare obviously strike some uncomfortable nerves – and on multiple fronts – personally, socially, ethnically and even where her family is concerned. Tension quietly builds in virtually all of Irene’s relationships, not just with Clare. But what is it leading up to? And what role will passing play in all this? That remains to be seen.

An old adage maintains “It’s possible to fool some of the people all of the time and all of the people some of the time, but you can’t fool all of the people all of the time.” However, given the potential backlash that can come from this practice, is it really wise to attempt to fool anyone at all, even if the perceived benefits that come from it would seem to offer suitable justification? That’s what “Passing” asks us to seriously consider, and not just in a racial context, but in any undertaking. And that’s crucial to remember when we set about making plans for our lives, particularly what we seek to bring into being. Such is at the heart of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents in manifesting the reality we experience.

At its heart, the practice of passing – no matter how it’s applied – calls for creating a deliberate deception, conditions that are intentionally false and designed to purposely mislead others. The nature of this is based on compromised beliefs loaded with potential consequences that could easily outweigh the benefits such an undertaking might afford. And, as a result, those who attempt it could easily be left with bigger problems to solve than those this practice was originally aimed at allegedly overcoming.

In light of this, those who actively engage in passing are pursuing the fulfillment of an objective at all costs without due consideration for the fallout that might accompany it. This is otherwise known as the practice of un-conscious creation or creation by default. What’s worse, though, is that it’s a practice undertaken with deliberate false intent, which could potentially amplify the impact of harmful side effects. It can also result in significant damage to one’s personal integrity, an outcome that could, at the very least, undermine one’s credibility, while also leading to possibly greater harm on so many other additional levels. Given that, one can’t help but ask, “Is it really worth it?”

As the film so poignantly shows, this truly has tremendous ramifications when it comes to matters of ethnic identity. But there are other ways in which it can manifest, too. For example, how “harmless” are Brian’s coy exchanges with Clare? Is he trying to pass off his behavior as being playfully polite, or is there something more to his actions? Likewise, is Clare merely seeking the friendship of racial kindreds through her interactions with Irene and the members of her household, or is there another agenda behind this, one that she’s seeking to pass off for something that it’s inherently not? Indeed, what are the real beliefs behind these initiatives, and what are they ultimately being implemented for? These efforts potentially speak volumes about the true selves of the creators involved here, but are others able to see them for who they are? There’s much at stake in circumstances like these, and not all of it may unfold as hoped for.

This, of course, raises an important core question when it comes to our materialization efforts: When we seek to fulfill a particular goal, what is the best approach? Should we rely on directed, untainted, forthright actions, or is it better to pursue carefully crafted courses that essentially amount to forms of passive deception? For most of us, the preferred answer should be obvious, but, if that truly is the case, why would anyone want to follow a different path?

In an age of improved social conditions and race relations, one could easily argue that courses different from passing should be followed. Yet, as we’re all aware, hindsight truly is 20/20, and those who succeeded at overcoming their difficulties through shrewd actions as this would likely argue that their efforts were worth it in the end. It’s quite a gamble, however, one in which coming up with the precise mix of manifesting beliefs needed to achieve the desired result is absolutely crucial, a challenging undertaking that may prove exceedingly difficult to get right – and all too easy to get wrong.

The practice of passing also places a burden on those who are the target of the intentional deception. That’s especially true here where John is concerned. One might wonder how he could get things as wrong as he does. However, when we embrace beliefs that allow us to see what we want to see, it’s easy to perceive our reality as something different from how others see it. Indeed, in light of what transpires here, as the film’s tag line – “Nothing is black and white” – so eloquently illustrates, this discrepancy takes on greater relevance than John realizes, both literally and figuratively. His obvious love for Clare is so strong that he willfully ignores what should be obvious, allowing the camouflage of his ignorance and her deception to take over. This raises questions involving matters of discernment and the need to practice it in order to see things as they truly are – and to avoid the potential for grave disappointment.

In the end, trying to be something we’re not carries implications that can go far beyond anything we can see when we launch into such endeavors, and they can emerge in a heartbeat, often without warning. Given that, then, the time-honored notion “To thine own self be true” takes on added meaning. We should remember that the next time we attempt to pass ourselves off as something other than what we truly are.

Eloquently and poetically shot in black and white, writer-director Rebecca Hall’s debut feature gives viewers much to ponder where ethnicity, tolerance and integrity are concerned. This is all brought to life by the fine performances of Thompson, Negga, Holland and Camp, backed by superb period piece production values and a fittingly complementary musical score. Several story threads feel a bit underdeveloped, but, on balance, this intriguing look at a challenging subject is sensitively handled, thought provoking and an excellent premiere effort from an aspiring filmmaker. The film has been playing at film festivals and in limited theatrical release, but it will be coming to Netflix for streaming in the near future.

How we handle the circumstances of our lives says a lot about who we are. Do we want to be known as someone who’s genuine, authentic and governed by principles of personal integrity? Or are we willing to engage in deceptive practices if they will seemingly get us what we want with an apparent minimum of effort? Think about the difference in those options and how others would view us depending on which one we choose. Indeed, what would it take to “pass” a test like this? And are we up to making the right choice? Ultimately we must each look to ourselves for answers, but we must also be willing to accept the consequences of what we decide, a determination best governed by two simple words: Choose wisely.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment