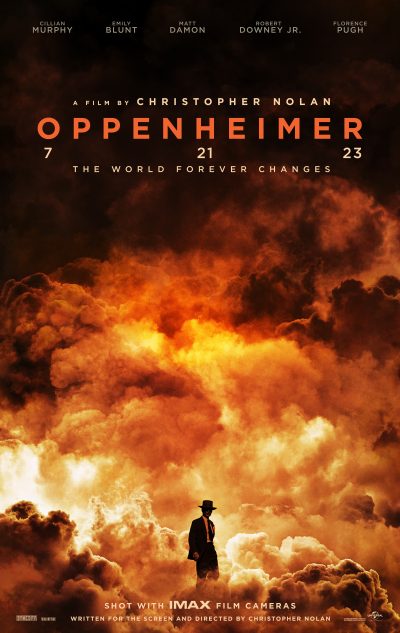

“Oppenheimer” (2023). Cast: Cillian Murphy, Robert Downey Jr., Emily Blunt, Matt Damon, Florence Pugh, Kenneth Branagh, Rami Malek, Gary Oldman, Tom Conti, Benny Safdie, Josh Hartnett, Casey Affleck, Matthew Modine, Jason Clarke, Alden Ehrenreich, James D’Arcy, David Krumholtz, Macon Blair, Josh Zuckerman, Jefferson Hall, Dane DeHaan, Dylan Arnold, David Dastmalchian, Emma Dumont, Matthias Schweighöfer, James Remar, Christopher Denham, Danny Deferrari. Director: Christopher Nolan. Screenplay: Christopher Nolan. Book: Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus. Web site. Trailer.

While writer-director Christopher Nolan’s biographical opus chronicles the events that were part of this epic venture, it goes much deeper, exploring the complex character of the man who led it. The film not only details the work of a brilliant scientist, but it also examines the complicated views of the man who was seriously torn about what he was doing. Oppenheimer understood the need to develop the bomb, given that Nazi Germany was already doing the same and that he couldn’t bear the thought of what might happen if an enemy as perversely evil as the Third Reich got its hands on such a weapon first (feelings no doubt stirred by his own Jewish heritage). At the same time, though, he was also cognizant of the massive destructive power that could be unleashed on humanity if the device were to be used as part of an active combat engagement, raining death and devastation down upon both military forces and innocent civilians. That left him with a profound quandary: How do I resolve these feelings for myself?

To understand where these sentiments came from, the film opens by exploring Oppenheimer’s background, revealing him to be a multifaceted thoughtful humanitarian. His interest in science was undeniable, having extensively studied the work of celebrated peers like Albert Einstein (Tom Conti), Niels Bohr (Kennth Branagh) and Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), particularly with regard to such cutting-edge subjects as quantum theory and the nature of black holes. But Oppenheimer also had a significant philosophical side, especially when it came to using one’s talents to make things better for mankind, an initiative he believed was not limited to technological advances and the use of scientific principles and practices. This inclination inspired a strong interest in what he saw as progressive politics and social movements, such as the work of labor unions and the American Communist Party. He was also an unapologetic donor to the left-wing rebel forces who fought in the Spanish Civil War.

Because of these somewhat unconventional and contradictory leanings (for the time), Oppenheimer was often seen as an enigma, a wild card who officialdom didn’t feel it could completely trust. This suspicion was fueled not only by his political and social views, but also by the fact that he studied overseas in the 1920s, earning his doctorate at Germany’s University of Göttingen, and by his circle of associates, including Communist Party member Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), with whom he was having an indiscreet affair while still married to his wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt).

Nevertheless, despite the doubts that swirled around him, Oppenheimer developed quite a reputation for his expertise, especially at the University of California, Berkeley, where his theoretical physics work attracted considerable widespread attention and a full professorship in 1936. This pedigree made him the leading candidate to head the Manhattan Project when it was launched in 1942. But, given his background, he was placed on a short leash by the military under the auspices of Gen. Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), a no-nonsense commander who was responsible for the construction of the Pentagon. Groves was seen as someone who could keep Oppenheimer on track and under surveillance, fully aware of the physicist’s questionable background.

As Oppenheimer launched into this venture, he surrounded himself with many of the brightest minds in the physics community, such as Ernest Lawrence (Josh Hartnett), Isidor Rabi (David Krumholtz) and Edward Teller (Benny Safdie). He was given relatively free reign to explore various possibilities at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, the principal research and development facility for the Manhattan Project. But, as work proceeded, he began to have doubts about the implications of his efforts. He was also skeptical about certain areas of research, such as Teller’s advocacy for the development of the hydrogen bomb, a weapon believed to be many times more powerful than the uranium- and plutonium-based devices that were being built at the time.

Needless to say, Oppenheimer’s mixed feelings caught the attention of government and military officials, prompting Groves to crack down on the project leader. In turn, Oppenheimer made his feelings known to the General, suggesting alternative proposals, such as conducting a demonstration of the weapon’s power on a neutral target, one specifically aimed at sparing the lives of military figures and civilians. And, later, as the war in Europe began drawing to a close, he even suggested not using the bomb at all, given that there would no longer be a need for it. But Oppenheimer’s reservations fell on deaf ears; after all of the money that had been spent on the bomb’s development and the desire of the US to become the world’s leading military force in the post-war era, the powers that be wanted to proceed as planned, using the weapon to end the war in the Pacific by dropping it on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Oppenheimer was particularly troubled by this decision, given that Japan had no nuclear ambitions or corresponding weapons programs in place, making the use of the bomb there little more than a case of military-based premeditated murder, regardless of the fact that such a move would assuredly bring an end to the war.

Despite being hailed as a hero for his accomplishment, Oppenheimer was uneasy with the emergence of the new nuclear age. He actively advocated for international cooperation in the regulation of this new technology, especially in military applications, hoping that such mutual efforts would help to curtail nuclear proliferation and the beginning of an arms race, especially with the Soviet Union. But those hopes were dashed as the USSR developed its own weapon and the US proceeded with its plans for building the hydrogen bomb. He hoped to counter these developments by becoming director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University and by being named to the General Advisory Committee of the newly created Atomic Energy Commission.

Through these new positions, Oppenheimer became acquainted with Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), a relationship that started out well but became strained in the early 1950s. Because his views about nuclear technology ran afoul of official sentiments during the rise of the Cold War, combined with his past associations with “radical” political and social movements, Oppenheimer came under increasing scrutiny, even raising questions about his patriotic loyalty and whether he was entitled to retain his government security clearance. He was subjected to intense interrogation by an investigatory committee, enduring hours of unceremonious grilling by “prosecutor” Roger Robb (Jason Clarke) while desperately being defended by attorney Lloyd Garrison (Macon Blair).

The hero celebrated for bringing an end to World War II thus suffered a devastating fall from grace. And, as this process was playing out, Oppenheimer’s colleague Strauss was undergoing a Congressional confirmation hearing with respect to his proposed Cabinet posting as Secretary of Commerce in the new Eisenhower Administration. Ironically enough, these two proceedings soon collided with one another, revealing an array of dirty little secrets about how that fall from grace came about – and how one man’s conscience was distorted all out of proportion simply because he adhered to views that were publicly out of favor at the time.

Despite all of the foregoing, in the end, Oppenheimer still had to wrestle with his ghosts, thoughts that were never far removed from his everyday life. They lingered like a haze that would never lift, no matter how his fortunes ebbed and flowed for better or worse. He had significantly changed the course of history, forever haunted by the chilling words of a passage from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Those words have echoed in the global consciousness since 1945, when the bombs were dropped on Japan. And, with the nuclear genie now out of the bottle, threats to the safety and security of the globe escalated, leaving us all on the precipice of annihilation at any given time. Oppenheimer felt responsible for this, and it was a concern that he could never shake. Like Prometheus giving mankind the gift of fire, Oppenheimer, too, was comparably tortured for the deed he carried out, tormented every day for the rest of his life – only this time, the punishment doled out to him was not that of a divine being but by that of his own hand.

Like virtually every American at the time, Oppenheimer wanted to see an end to the war. Simultaneously, though, he also had to ask himself, “At what cost?” Use of the weapon would undoubtedly bring the conflict to a close, but what consequences would that carry? How many would die? In particular, how many innocents would be killed? And what about afterward – would the bomb’s deployment set off a chain reaction prompting further use of nuclear weapons by the US and the development of comparable devices by other nations, both friends and foes? There were also chilling doubts that lingered during the prototype’s development, such as the possibility that some theoretical calculations showed a nuclear explosion might lead to an unending, uncontrollable reaction capable of burning off the earth’s atmosphere, leaving the world with a cure more deadly than the disease it was meant to treat.

To resolve this conundrum, Oppenheimer had to engage in some profound soul searching, examining his heartfelt beliefs to devise a solution. That’s crucial given that our thoughts, beliefs and intents play a crucial role in the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in the manifestation of our existence. It’s not clear whether or not Oppenheimer was aware of this school of thought, but, considering his in-depth knowledge of related scientific subjects like quantum physics and his familiarity with analogous metaphysical studies like those found in ancient Hinduism, there’s a good chance he might have been cognizant of this discipline’s principles and their implications.

If that were the case, then why did he struggle so much with his conflicted feelings? There are several possibilities that come to mind. To begin with, Oppenheimer was genuinely attempting to reconcile contradictory beliefs, and that’s important to remember, given that such paradoxes are one of most significant impediments to our creations materializing as desired. Contradiction can cause our desired manifestations from being realized in their hoped-for forms (frequently tainted by unexpected and often-devastating side effects), or it can even prevent those creations from appearing at all.

On top of that, Oppenheimer had to contend with the fact that this undertaking was a joint effort, an act of co-creation in which all of the participants had a stake in how things turned out, each of them seeking the fulfillment of their own respective agendas. Even though Oppenheimer headed the Manhattan Project, there were thousands of collaborators working under him, most of whom were unaware of what their peers were doing, a product of the rigid compartmentalization that had been implemented to maintain the secrecy of the endeavor. Then there were the “outsiders” who had a vested stake in the project – those who made up the emerging US military industrial complex, most of whom already had their sights set on how they could benefit from the development of nuclear technology after the war, even before the current conflict was over.

Despite Oppenheimer’s considerable influence, he was only one voice in this chorus. What’s more, he had his past clinging to him like a millstone, something that those with agendas could use as a weapon against him if necessary. He thus often found himself manipulated into making compromises – despite what his conscience was telling him – in order to stay in the game in hopes that he could make his views known and, in turn, a difference.

But, as Oppenheimer’s story played out, as this film shows, he continually had to wrestle with the many challenges that arose out of this scenario, often manifesting in ways that went against his fundamental humanitarian views, especially during the Red Scare and Cold War of the 1950s and ’60s. It was an unenviable position, to be sure, one that truly mirrored the story of Prometheus (and, in some ways, that of Sisyphus, too). His odyssey could thus be seen as simultaneously heroic and tragic. He gave the world his own version of the gift of fire, but this one was – as the Irish rock band U2 once wrote – truly unforgettable.

Telling the story of a larger-than-life individual truly calls for a larger-than-life film, and that’s precisely what writer-director Christopher Nolan has come up with in his latest feature outing, handily the best work of his career. Nolan’s three-hour opus provides viewers with a comprehensive biography of this brilliant and thoughtful yet often-inscrutable and surprisingly naïve physicist who took on a patently dangerous venture that left him morally conflicted about the nature of his creation. The story, which spans several decades of the scientist’s life, chronicles his development of “the gadget” (as it was called) and the fallout he suffered as a consequence of his left-wing pacifist political leanings and his efforts to keep the released nuclear genie from getting out of control. The film is admittedly a little overlong and probably could have used some editing in the opening and final hour, but, in the interest of telling the whole story of Oppenheimer’s journey, its length is understandable (and, consequently, justifiable).

The picture’s production values are all top shelf, especially its brilliant cinematography, stirring original score and superb sound quality, an element that truly leaves audiences with a bona fide visceral experience. Moreover, the narrative is skillfully and eloquently brought to life by this offering’s outstanding ensemble cast, including Murphy, Damon, Conti, Safdie, Blunt, Pugh, and, especially, Downey, who delivers a stellar, award-worthy supporting performance showing acting chops that I never knew he possessed. “Oppenheimer” is easily the best film of the summer movie season, if not all of 2023 thus far. It packs a potent punch and delivers a message that we can all never hear too often, poignantly reminding us all of the importance of not falling prey to the same Promethean burden that Oppenheimer was forced to shoulder.

Oppenheimer’s circumstances could readily be looked upon as intolerable, a task that virtually all of us might have been unwilling to take on, and it certainly took a toll on him, especially when his voice was effectively drowned out. However, despite these difficulties, perhaps his efforts were meant to get the ball rolling on a larger, long-term discussion that has carried on to this day – the dangers of mankind’s reckless inclination toward wanting to destroy itself. Throughout history, we as a species have often blindly allowed ourselves to head down a variety of self-destructive paths, all of which we’ve managed to successfully stave off thus far. But how many times must we continue doing this? When are we ever going to stop? And what will it take for us to come to that realization? Perhaps the potency of the nuclear threat may finally end up being the last straw in this regard. But, to reach that conclusion, we must first be collectively convinced of the deadly ramifications of pursuing this possibility so that we can at last dispense with the prospect of self-annihilation as a viable path to follow. For his efforts, it could be argued that Oppenheimer got that ball rolling, even if it came at a terrible cost to himself. But, if it eventually achieves the sought-after result, then perhaps it can viewed as worth it in the end. Let’s just hope it’s the end we need and not the one we’re trying to avoid.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment