If it’s March, it wouldn’t be complete without the Gene Siskel Film Center Chicago European Union Film Festival. After several years of adjustment, abbreviation and cancellation due to COVID-19 concerns, the festival finally returned to normal form this year for its 26th annual edition. I managed to screen 10 of the event’s 24 offerings, which are summarized below. Check out what’s new in cinema across the pond!

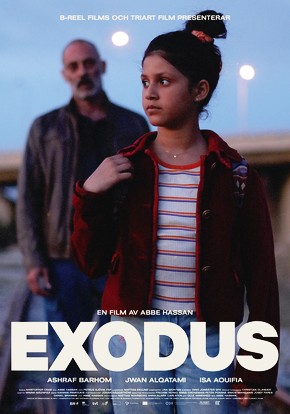

“Exodus” (Sweden) (4.5/5); Imdb.com (9/10) Web site Trailer

The refugee crisis (especially those escaping from Syria) is an issue that is finally getting its due cinematically, first with the Netflix fact-based offering “The Swimmers” (2022) and now with this impressive debut feature from writer-director Abbe Hassan. The film follows the odyssey of a young Syrian girl (Jwan Alqatami), travelling alone, who flees to Turkey from her homeland on her way to Sweden for a reunion with her sisters and parents. But, upon exiting the crowded shipping container that transported her on the first leg of her journey, she’s met with a raid by Turkish immigration authorities, barely escaping in the unexpected company of one of the exploitive smugglers who organized her flight to freedom (Ashrof Barhom). Thus begins a trek through Europe as this seemingly mismatched duo makes its way to Sweden, a perilous trip that embroils the protagonists in an engaging array of challenges and revelations, especially the uncovering of the many different sides of these complex characters, superbly portrayed by Alqatami and Barhom. As this story plays out, the filmmaker effectively weaves together elements from a variety of genres, including action-adventure tales, thrillers, emotionally touching dramas and road trip/buddy movies, successfully depicting the refugee saga for it truly is – a bittersweet experience filled with joys, triumphs, disappointments and tragedies. It draws much-needed attention to the plight of these downtrodden souls seeking safety from an insane conflict that’s needlessly displacing so many innocents caught in the crossfire, just one of many such clashes currently occurring around the world. “Exodus” is a genuinely compelling watch, one that truly deserves a mainstream theatrical distribution, as well as recognition for the attention it so absorbingly draws to this urgently heartbreaking crisis.

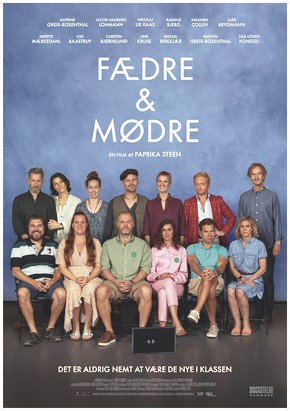

“Fathers and Mothers” (“Fædre og mødre”) (Denmark) (4/5); Letterboxd (4/5), Imdb.com (8/10) Web site Trailer

Ah, parents these days. They’re not what they used to be, which is unfortunate, as this scathing Danish comedy-drama aptly illustrates. Director Paprika Steen’s latest serves up a wickedly funny take on a group of upscale parents who have enrolled their children in an elite private school designed to help kids maximize their potential. Despite their seemingly good intentions, however, the parents in this story unwittingly compete with one another to be the best über-moms and dads possible, particularly when it comes to showing off their degrees of social consciousness and political correctness. In the process, they ostensibly engage in polite but toxic games of one-upsmanship with each other, a form of posing that eventually transforms supposedly enlightened discussions into bitter arguments that violate their so-called principles, accompanied by bad behavior that makes anything their kids do look tame by comparison. Much of this plays out at a getaway country weekend for the parents and their children, where a type of unconscious role reversal takes place in which the grownups show their true colors on a variety of fronts as their more mature kids look on in shock, disbelief and contempt. Some may view all this as a mean-spirited exercise, but it’s actually spot-on when it comes to poignantly portraying the hypocrisy of those who believe that their you-know-what doesn’t stink. Given the multiple characters and story threads at work here, the film can be somewhat episodic at times, and a few of the narrative tracks don’t feel fleshed out as fully as they might have been. Nevertheless, this offering paints an authentic picture with its share of incisive dramatic moments, as well as ample biting humor that’s depicted directly, by implication and even in deftly placed nonverbal visuals. When viewed in this context, it’s apparent that there’s a lot more going on here than may initially and superficially meet the eye. There’s a great deal of insightful material tightly packed into this package, but it mostly involves things that need to be said – and, ultimately, in ways that are very much in your face. Let’s hope that those who need to get the film’s message indeed do considering what’s at stake.

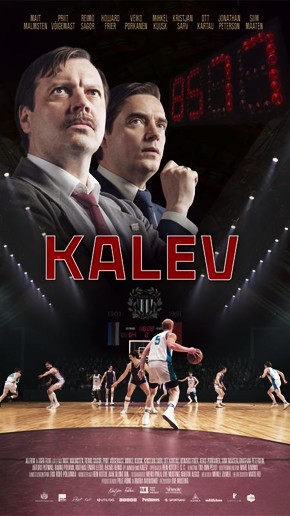

“Kalev” (Estonia) (3.5/5); Letterboxd (3.5/5), Imdb.com (7/10) Web site Trailer

Sports dramas – especially those where the athletes are competing under trying conditions – have become a staple in the movie industry over the past few decades. They all tend to follow a fairly standard formula in which underdog competitors aspire to greatness while wrestling with ancillary challenges that threaten to derail their efforts, divert their focus and force them into difficult choices. These pictures also feature common themes like inspiration, tenacity and the virtues of teamwork. And we all know the outcomes of these pictures going in, so their conclusions rarely, if ever, come as a surprise; the suspense is in watching how our heroes overcome their ordeals and reach their destinations. Such is the stuff of the latest offering in this genre, “Kalev,” the fact-based story of the Estonian national basketball team in its 1990-91 bid to win what would be the final USSR Basketball Championship before Estonia declared independence from a Soviet Union that would collapse not long thereafter. Writer-director Ove Musting successfully hits all the right (i.e., expected) notes and throws in a few delicious unanticipated twists in this feature film debut, an economically told and edited offering that moves along at a refreshingly brisk pace, punctuated with stirring re-created game sequences that make viewers feel like they’re right in the middle of the action. While the narrative and screenplay might have benefitted from a little more originality, that’s a minor concern in the overall scheme of things given how many aspects it gets right. Die-hard sports fans (particularly basketball lovers) will surely enjoy this one while learning a little more about the inner workings of Soviet politics and the fates of the courageous Baltic republics (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) that led the charge in breaking free from the oppressive rule they were forced to live under for decades. Here’s to the winners!

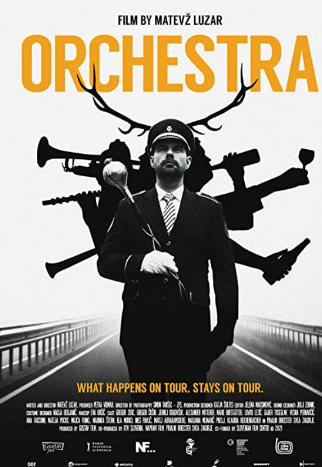

“Orchestra” (“Orkester”) (Slovenia) (3.5/5); Letterboxd (3.5/5), Imdb.com (7/10) Web site Trailer

They say that “What happens in Vegas, stays on Vegas.” And, based on this second offering from writer-director Matevž Luzar, the same could be said for the members of a Slovenian brass band on tour in rural Austria. Told in a series of interlaced vignettes, this monochrome comedy-drama follows the exploits of these hard-partying musicians who seem more preoccupied with having a good time than with the performance they’re about to give. The story threads involve both those on tour, as well as their families left behind at home, all of whom engage in their share of comparably fun-loving but often-questionable behavior. Through the various segments, an array of revelations emerge, many of them humorous though karma-laden and not especially honorable, essentially engaging in actions that could best be summed up as adults behaving badly. The strands of this tale don’t exactly send complimentary messages or present examples of conduct particularly worth emulating, though they do spotlight the perils and consequences of comeuppance, often with hearty laughs. Not all of the sequences work equally well, but those that hit the mark do so with a clever mix of both subdued, rapier wit and raucously outrageous sight gags, along with poignant dramatic and emotional moments that give viewers pause to think. “Orchestra” may not be especially memorable cinema, though it is a modestly amusing guilty pleasure that’s a fun way of spending a few hours at the movies.

“The Quiet Girl” (“An Cailín Ciúin”) (Ireland) (3.5/5); Metacritic (7/10), Letterboxd (3.5/5), Imdb.com (7/10) Web site Trailer

Truly affecting domestic dramas are among my favorite types of films, and writer-director Colm Bairéad’s debut narrative feature takes a noble stab at the genre, one that’s tender and moving but that doesn’t quite land itself in masterpiece territory. Set in rural Ireland in 1981, this film, whose dialogue is mostly in Irish Gaelic, tells the story of a misunderstood young girl, Cáit (Catherine Clinch), whose dysfunctional family can’t be bothered with her, so she’s sent to live with her mother’s relatives for the summer until Mam delivers yet another child who’s likely to be just as unwanted as she is. While separated from her parents and siblings, however, she discovers a whole new way of living – and loving – with people whom she’s never met. And her presence in their household does much to rejuvenate their lives as well, a relationship that benefits all concerned – that is, until it’s time for Cáit to return home. The emotions stirred here are indeed palpable, but, given the picture’s novella source material, the narrative is a tad thin, requiring the picture to be embellished with plenty of gorgeous nature shots, emotive closeups and a heart-tugging background score to shore up the lean aspects of this offering. There’s certainly nothing wrong with any of that; in fact, it provides viewers with more than most other comparable releases supply. However, as an offering that earned best foreign language/international film nominations at both the BAFTA Awards and the Oscars, I expected more, a film that would truly have me more engaged and potentially on the verge of tears at any time, goals that came up a little short. It certainly raises important issues related to child neglect and emotional abuse, and it shows that change is possible where such circumstances prevail, but it just didn’t grab me that way I would anticipate a picture like this should. Enjoy it, but don’t be disappointed if it doesn’t live up to your expectations as well.

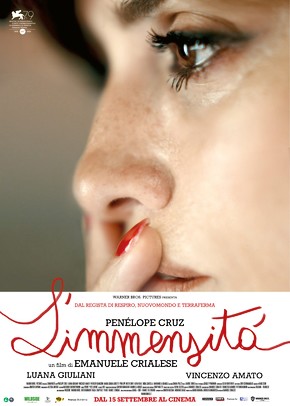

“L’Immensità” (“The Immensity”) (Italy/France) (3/5); Letterboxd (3/5), Imdb.com (6/10) Web site Trailer

How frustrating it can be when you watch a movie that has a lot of tremendous moments but doesn’t hang together well as a complete whole. Such is the case with this latest offering from writer-director Emanuele Crialese, which tells the story of a family in the midst of multiple domestic crises. Set in Rome in the 1970s, the picture follows the life of Clara (Penélope Cruz), the depressed wife and mother of three who’s married to an abusive, philandering, often-disconnected husband (Vincenzo Amato), and her attempts to cope with her circumstances. Clara loves her children dearly, but the young ones all have challenges of their own, especially her eldest, Adriana (Luana Giuliani), a teen who’s struggling with gender identity issues. Clara and Adriana seek various forms of escape, as depicted in several fantasy sequences and regular forms of play (all captured with a terrific sense of humor), but are those diversions enough to take away their heartache? The film also seeks to address a number of Italian cultural matters, such as the privileged role of men and the expected subservient place of women, dynamics that unfold in the principal narrative as well as in ancillary story threads. Sadly, while these are all noteworthy elements of the story, there’s a little too much going on for the picture to hold everything together cohesively, especially when crammed into is relatively brief 1:37:00 runtime. Also, a number of the story’s aspects are presented a little too vaguely for my taste, leaving them open more to ambiguous, unfocused interpretation than nuance or even bona fide clarity. To its credit, however, when the sequences work, they do so quite effectively, in large part thanks to the fine performances of Giuliani and, particularly, Cruz, whose ravishing elegance recalls a young Sophia Loren. It’s unfortunate that this offering isn’t better fleshed out; it could have stood to either have some elements cut out completely or to expand and elaborate on others, improving the overall narrative. As it stands now, however, this release feels choppy, underdeveloped and incomplete, despite the strength of those aforementioned moments. Those are the sequences that make this offering work; it’s just a shame that there weren’t more of them and that they were better tied together.

“Talking About the Weather” (“Alle reden übers Wetter”) (Germany) (3/5); Letterboxd (3/5), Imdb.com (6/10) Web site Trailer

What truly makes us happy in life? Is it our ability to impress others with our accomplishments and an impressive body of knowledge? Or is it the simple things, like family, friendly conversation and spending time in the company of those we love? Those are the questions posed in writer-director Annika Pinske’s debut feature. The film tells the story of Clara (Anne Schäfer), a middle-aged college lecturer and doctoral candidate living in Berlin who seems confused and uncomfortable with her existence. That gets called into question when she pays a weekend visit to her hometown in rural eastern Germany, a community that was once part of Communist East Germany and has had trouble adjusting to Western economic and social ways. The contrasts between these two locales couldn’t be more extreme – an academic ivory tower enclave in a cosmopolitan city and a folksy, economically challenged village where life is comparatively simple. The differences in atmosphere and attitudes are also palpable; Clara’s life in Berlin is filled with toxic psudointellectual toadies deeply engaged in mental masturbation and professional one-upsmanship, while the country folk – who are often looked down upon as homespun rubes – converse about things like the weather, the arrangement of items on platters of food and the people around them. The question for Clara then becomes, which of these options is more fulfilling? This sentiment may not be especially original, though it’s good for us as social beings to be reminded of it now and then, and that’s what this film seeks to achieve. Regrettably, it doesn’t pull off that accomplishment as well as it might have. The opening segment, before Clara embarks on her trip, goes on far too long and really runs the stilted intellectual discussions between her and her peers into the ground, making viewers wonder what exactly are they watching. It’s only when we see her out of her collegiate element that the purpose behind much of what preceded it becomes clear, and that subsequent segment, unfortunately, tends to get short shrift and is often presented in a fashion whose message and character are a little too obvious. Better balance in the writing, editing and directing would have helped immeasurably and made the film and its meaning more effective. But, then, for a first-time feature, I suppose it takes a new director some time to get these kinds of things sorted out a little better, and that’s apparent in the final product here. It represents a nice try for a filmmaker who appears to have some potential but who needs to get the kinks worked out of her material going forward.

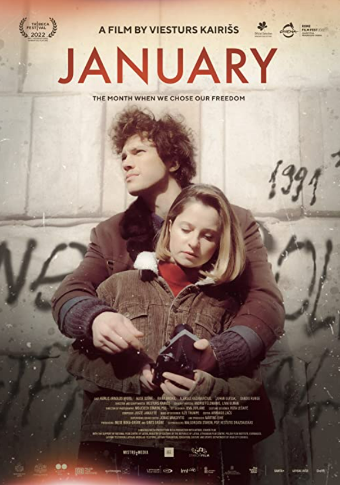

“January” (“Janvāris”) (Latvia/Lithuania/Poland) (2/5); Letterboxd (2/5), Imdb.com (4/10) Web site Trailer

The 1991 independence movement led by the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia in the days preceding the collapse of the Soviet Union was a dynamic but dangerous time in the re-emergence of those nations as sovereign states, a subject that has provided the basis for a growing number of recent cinematic releases. Because of these conditions, it was also a time when the citizens of those republics had no clear indication of what the future would hold. Could they successfully break away, or would they come under the harsh retribution of their superpower occupiers? And what did those residents think about these possibilities – should they support revolution or remain ostensibly loyal to those who could potentially crush them with little effort? When these circumstances are added to the personal uncertainty associated with someone who’s in the throes of coming of age, these questions loom even more profoundly. Such is the case in this historical drama about an aspiring young Latvian filmmaker (Karlis Arnolds Avots) looking to find himself amidst all of the surrounding chaos, both in his homeland and in neighboring Lithuania, either as an experimental auteur or a documentarian of what was transpiring around him. The protagonist also wrestles with an on-again/off-again romance involving a cinematic colleague (Alise Danovska), as well as his decision of whether or not to honor his Soviet conscription obligation. On the surface, all of this would appear to offer the makings of a powerful, compelling, first-class drama, but the unbalanced execution of writer-director Viesturs Kairiss’s narrative keeps the film from living up to that potential. The principal issue here is a story that takes far too long to get off the ground, incorporating a wealth of easily excluded extraneous material that adds little to capturing the character of the time and the merits of its associated scenario. And, when things finally do get on track, there’s a good chance viewer interest may have been lost long by that point (I know it was with me). It’s baffling that this offering was considered worthy enough to win the best international narrative feature at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival, along other comparably dubious accolades. In short, this should have been a terrific picture, but, unfortunately, it represents a lost opportunity for telling an engaging story about a tense time and how a lost soul tries to find his place in it.

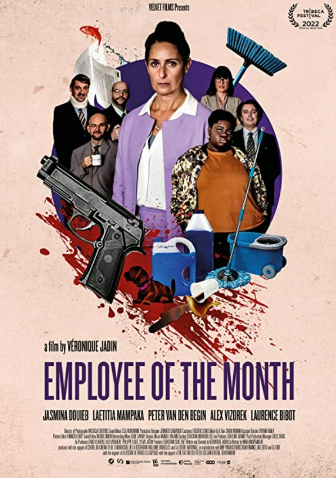

“L’employée du mois” (“Employee of the Month”) (Belgium) (0.5/5); Letterboxd (0.5/5), Imdb.com (1/10) Web site Trailer

It’s hard to convey my level of disappointment (and disgust) when it comes to this perfectly dreadful movie. As one of the pictures I was most looking forward to seeing at the festival, I walked out thoroughly appalled by what I had just watched. What should have been a screwball dark comedy, with a premise loosely based on elements from the classic workplace farce “9 to 5” (1980) and the long-running hit TV sitcom The Office, somehow managed to find ways to completely miss the mark from start to finish. To begin with, as a picture that’s supposed to be a comedy, it simply wasn’t funny, with virtually every bit failing to land. Then there was the pacing, which was far too laborious for a story that should have moved by at breakneck speed. But, perhaps most importantly, writer-director Véronique Jadin doesn’t appear to have a handle on what distinguishes macabre humor from nasty, mean-spirited poor taste. I can’t believe how many times during the picture I caught myself saying “There’s absolutely nothing funny about that.” And, even if this production were meant to be a goofy, gory tale a la movies like “Raw” (2016) or “The Columnist” (“De kuthoer”) (2019), it’s not nearly campy, creative or playfully over the top enough to be able to pull off that feat. What’s more, the film’s attempts at making statements about equal pay, toxic masculinity and sexual harassment in the workplace are far too obvious and heavy-handed, expressing sentiments that virtually anyone save for those who’ve spent years living in a cave should readily be able to recognize without being beaten over the head. Thankfully, the only saving grace here is the picture’s mercilessly short 1:18:00 runtime, but even that feels eons longer than it actually is. I suppose the most troubling thing I find about this offering, however, is that I actually heard audience members laughing during this travesty. It made me wonder about people these days and how they could possibly see the humor in any of this. There’s a big difference between a deft touch and a sledgehammer approach, even in dark comedies, but the filmmaker apparently doesn’t recognize it, and that shows in her work.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment