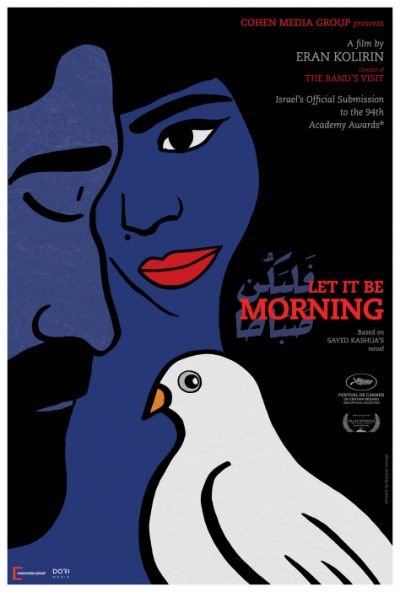

“Let It Be Morning” (“Vayehi Boker”) (2021 production, 2023 release). Cast: Alex Bakri, Juna Suleiman, Maruan Hamdau, Samer Bisharat, Yara Elhan Jarrar, Arin Saba, Doraid Liddawi, Salim Daw, Izabel Ramadan, Ehab Elias Salami, Nadib Spadi, Costa Kaplan. Director: Eran Kolirin. Screenplay: Eran Kolirin. Book: Sayed Kashua, Let It Be Morning (2004). Web site. Trailer.

These circumstances quietly loom large in this film, which opens with a traditional Arabic wedding celebration in a small rural community populated almost exclusively by Israeli Palestinians. Sami (Alex Bakri), a successful, upwardly mobile family man living in Jerusalem, reluctantly attends the ceremony, which takes place in the town where he grew up, a place he left behind long ago. He sees it as somewhat homespun and quaint, the embodiment of values from which he’s moved on in favor of a more urban, cosmopolitan way of life.

Sami also has reservations about spending time with extended family members with whom he believes he has little in common anymore. There’s Sami’s brother, Aziz (Samer Bisharat), the groom, and his demure bride, Lina (Yara Elhan Jarrar), both of whom he sees as timid and not especially adventurous or ambitious. Then there’s his reserved sister, Rola (Arin Saba), and her political aspirant husband, Nabil (Doraid Liddawi), who self-righteously seeks to advance his career by aggressively exposing and condemning the practices of the illegal workers crossing into Israel from the territories. Sami also has to deal with his father, Tarek (Salim Daw), a proud Palestinian who’s convinced his son will soon leave Jerusalem and cheerfully move back to his hometown, a belief that appears to be colored somewhat by the onset of an emerging form of dementia. In fact, about the only family member Sami can tolerate is his mother, Zahara (Izabel Ramadan). She’s not especially happy with her lot in life but puts up with it out of obligation. Sami understands her plight, and she appreciates his desire to distance himself from where he grew up. These conditions provide a basis for a bond between them; indeed, they’re about the only family members who truly have a connection and understand one another.

The trip also means that Sami must spend time with his immediate family, something he appears to have been doing less of in recent months. Sami’s wife, Mira (Juna Suleiman), has tired of the widening chasm that has been opening up between them. She suspects – and correctly so – that Sami is having an affair back home (and with a Jewish woman at that). In fact, about the only thing that’s keeping them together is their young son, Adam (Maruan Hamdau), whom they both appear to adore. Still, the relationship between Sami and Mira seems mostly obligatory at this point, and the tension between them serves as a frequent source of intensifying conflict.

So, with this backdrop, Sami, Mira and Adam attend the wedding, with Sami hoping to get it over with as quickly as possible, an unlikely objective given the length of typical Arabic marriage celebrations. But, by late evening, the festivities wind down, at last making it possible for Sami to begin the drive back to Jerusalem. However, upon reaching the outskirts of town, he and his family are met by a contingent of Israeli troops. They inform Sami that the road ahead is closed for an unspecified period of time, forcing him, Mira and Adam to return to his parents’ house. They go there under the impression that it will be just to stay the night. But, as they find out the following morning, it’s about to be for a duration far longer than anticipated.

Sami soon learns from a doe-eyed Israeli soldier (Costa Kaplan) that the reason for the road closure is being kept secret, which is part of the reason why the length of the shutdown is also unknown. Sami is upset at being stuck, partly because he no longer wants to be there, but also because he’s worried that his delayed departure will place his much-coveted job in jeopardy. And that concern is further complicated when he discovers that cell phone service to the village has been cut off, making it impossible to even notify his employer about what is transpiring.

Not long thereafter, Sami and the residents of the village learn that more than just the phone service has been curtailed. The electricity goes next, followed by the water supply. And, as the lockdown continues, the town begins running out of food and other basic supplies, all without explanation. What’s going on here?

As supplies dwindle and tensions rise, tempers soon begin to flare. Too many people with too much time on their hands and no answers in sight begin engaging in conflict and various forms of antisocial behavior. These conditions also open doors for opportunists, such as Ashraf (Nadib Spadi), a local bully who assumes the role of an alpha strongman. Ashraf is particularly abusive toward Abed (Ehab Elias Salami), one of Sami’s childhood friends. Sami was initially reluctant to spend any time with Abed when attending the wedding; he looked down on his longtime acquaintance, seeing him as yet another reason for why he fled his hometown for life in Jerusalem. But, now that Abed is having the screws put to him under these trying conditions, Sami feels for him and wants to try and help him out, especially when he learns that Ashraf and his goon squad appear to be quietly cooperating with Israeli authorities during the lockdown in exchange for preferential treatment.

In fact, as time passes, Sami begins to have a change of heart about many of the issues for which he previously lacked tolerance. Why? Well, having time on one’s hands can be put to use in a number of ways. Some, like Ashraf, use it for personal gain. But, for others, like Sami, it affords a much-needed opportunity for reflection. As the matters that previously occupied much of Sami’s attention begin to take a back seat, his priorities gradually change. For example, he tries to help Abed, both in his dealings with the neighborhood thug, as well as in helping him get over the draining frustration he’s experiencing with trying to reconcile with his ex-wife, a reunion that Sami knows will never happen and that would never do his friend any good.

Then there are Sami’s relations with his family. He seeks to patch up things with Mira. He becomes more tolerant of his dad. And he tries to inspire Aziz to grow a backbone, especially in helping him overcome the quietly embarrassing “performance anxiety” he struggles with when it comes to handling his apparently unconsummated marital relations. Slowly but surely, others around Sami begin following suit in their own personal endeavors, the net effect of which is a town full of residents who have chosen to knock down the walls surrounding them. If they can accomplish such changes in their own everyday dealings, there’s no telling what else they might accomplish by applying those principles to the larger issues that they all face collectively. Indeed, it’s amazing what’s possible when we concertedly put our minds to something.

Of course, even as these personal walls begin to collapse, there remains the biggest obstacle of all, the unexplained roadblock that’s keeping the village residents confined and cut off from life’s basic necessities. What will it take, if anything, to eliminate this last-remaining barricade? That remains to be seen, but, if nothing else, it will undoubtedly require a joint effort to make it happen, not to mention a combination of the correct actions and intents. Are Sami and the residents up to it? And, if so, when and how will it finally take place?

To begin with, the residents of the village come to understand that their enclosures are creations of their own making based on the beliefs that they hold. That’s a crucial realization since that understanding prompts them into recognizing that those beliefs are responsible for manifesting the reality they experience, a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that makes such outcomes possible. At the same time, such an awareness of the mechanics of this process is essential to grasping how it fundamentally works. Without it, those seeking to alter their lives are essentially unable to do so, at least to the degree they hope to achieve that goal.

At bottom, the characters in this story must come to understand that the materialization of the existence they experience is as much an internal process as it is an external one. Since our beliefs emerge from within us, they’re responsible for what springs forth from them physically. And, because beliefs are innately changeable, it’s possible for what they produce to be changeable as well. Of course, that won’t happen until they (and we) intrinsically understand that.

If Sami and the village residents want something different from the limitations they’re seemingly saddled with, they must be able to envision alternate existences free of them, prospects that originate from their underlying beliefs. This involves grasping a broader perspective about how reality functions, one that’s akin to the experience of the prisoners trapped in the allegory of Plato’s Cave, in which those individuals base their understanding of existence only on the incomplete knowledge they derive about it from shadows that appear on a wall before them. Were they to turn around and see how those shadows are created, it would open a broad new perspective for them, not unlike what the characters in this film would experience by expanding their view of how reality operates.

Interestingly, as frustrating as it may seem, the lockdown helps to make this new understanding possible. By giving them the time needed to reflect on their circumstances – free of the distractions that had previously prevented the village residents from doing so – this community-wide confinement provides them with the means to appraise what’s transpiring around them. It also makes possible the chance to change it, based on what they want.

In many ways, given the despair they’re each experiencing, this scenario could be seen as a form of undergoing “the dark night of the soul.” The harsh conditions of their current existence push them toward looking for better options, alternatives that they come to understand must begin with them if they’re ever to be realized. So, if they now grasp that, then why are they staying put in realities characterized by inherently unsatisfying limitations? It’s indeed time for a change. They yearn for the dawn of a new day, one that encourages the manifestation of their passionate plea “let it be morning.”

And that’s precisely what unfolds here, on both individual and collective stages. Sami is obviously the one most impacted, considering how many enclosures he’s erected around himself. He at last sees the self-imposed prison he’s built regarding his views about what kind of life he wants for himself. It’s kept him from appreciating what his family (both immediate and extended) might have to offer him. It’s kept him from seeing that his life in Jerusalem may not be all it’s cracked up to be. And it’s kept him from grasping the irony that his supposedly “freeing” romantic affair could be just as much a trap as he thinks his marriage is. Liberating himself from all of these confines opens up a new range of possibilities for him, lines of existence that could well prove far more fulfilling for him than what he has been experiencing – and enduring – for some time.

The same is true for those around him, too. Mira realizes that Sami may not be the louse she’s come to believe he is. Aziz realizes he just might be able to satisfy his wife after all. Abed understands that he doesn’t need his ex-wife to be happy. And, at the same time, others, like Ashraf and Nabil, get wake-up calls that poignantly drive home what can happen when they employ their beliefs for self-serving purposes, especially those that inflict harm and ill will upon others. These are all important revelations, and they’re all driven simply by changing the beliefs that manifest them.

The foregoing illustrations examine what can happen in our existence on an individual level, but the effects of this process can be felt more widely, on a collective level, as well. For starters, given the widespread displeasure that everyone was experiencing in his or her personal lives, they all realized to some degree that they needed to make changes, and the collectively induced materialization of the lockdown helped to make those alterations possible. By pooling their belief resources in a mutual undertaking – creating the community-wide confinement – the residents gave each other the time and space needed to reflect on what they each wanted to change in their lives. They may not have been conscious that they were doing so – or even be aware of the very school of thought behind this process – but the outcomes they produced yielded results that they could all benefit from. That’s quite a collaboration, one that works wonders for everyone, despite the seeming inconveniences that might have been caused along the way.

However, as effective as the foregoing co-creation may have been in addressing everyone’s individual issues, the collective matters – those affecting everybody – remain. This, of course, relates to the roadblock – why it exists and how it’s affecting everyone in the village, whether they’re permanent residents or merely visiting from elsewhere. It’s also important to recognize what it symbolizes, given that it’s a physical metaphor for issues affecting the Palestinian population throughout Israel.

In essence, the film is suggesting that the purpose behind the roadblock reflects a view widely held among much of Israel’s non-Palestinian population. Cordoning off Palestinians in this manner, keeping them separate and even denying them the basic necessities of life, could almost be looked upon as a modern-day form of apartheid. It’s an outlook shared by many Palestinians who have experienced treatment like this firsthand. And it’s a policy that they’ve grown to resent, seeing it, as director Eran Kolirin has observed, as living under a state of siege.

The roadblock thus serves as a symbol of the foregoing, and the community’s reaction to it in the film reflects the growing resentment that Palestinians living across Israel have come to feel about such policies and practices. It mirrors an emerging movement, an act of defiance and resistance toward treatment that’s becoming less tolerated, a collective prison that those impacted by it increasingly wish to see torn down. The time for overt activism in this regard may not have arrived as yet, but the imagery included in this picture illustrates a development that could well be on its way now that those opposing it see the purpose behind its implementation. And, if such confinement is unacceptable on a personal level, what would make anyone believe that it could or should be tolerated on a collective level either?

Everyone may not agree with these views. But, then, how could anyone approve of the continued persistence of limitations and restrictions like these, whether employed on either an individual or collective basis? Overcoming fears and limitations is one of the chief intentions behind this philosophy, and it deserves its proper due, something this film seeks to encourage. It’s good advice, no matter where anyone lives and under what conditions they’re experiencing – or looking to escape.

Prisons come in a variety of forms – some imposed on us, others self-created – but, regardless of how they materialize, they all have the same impact: a means for keeping us locked in place. The myriad permutations they embody and the ways in which they affect the members of a family and their community provide the focus for this gentle comedy-drama. As troubling as the narrative in this offering may appear, though, events unfurl in unexpected ways, often laced with humor, satire and heartfelt emotion. The developments in this story tend to evolve somewhat slowly, but the payoffs are definitely worth it in a film that’s beautifully told and photographed, backed by a gorgeous original score. Admittedly, the picture tends to be somewhat episodic at times, but it manages to cover all its bases and leaves no plot threads unresolved.

In addition to its designations as Israel’s official selection to the 94th Academy Awards in 2022 and as an Un Certain Regard Award nominee at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, “Let It Be Morning” seems to have taken an inordinately long time to make it into general release, but the wait was definitely worthwhile. This touching, sincerely realized work is a genuinely heartrending cinematic gem, one of the finest films to come out of Israel in quite a while. After a brief theatrical run earlier this year, the picture has since become available for streaming online and on home media.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment