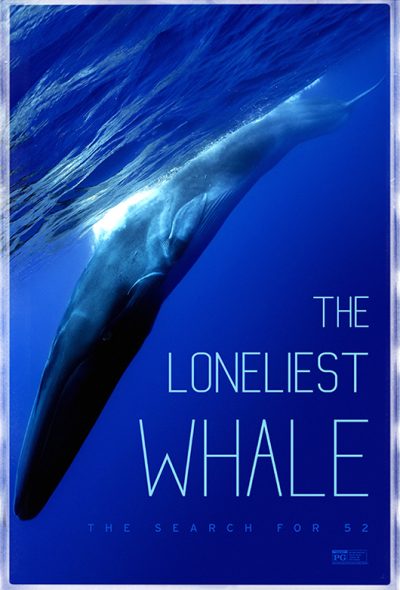

“The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52”(2020 production, 2021 release). Cast: Joseph George, David Rothenberg, Christopher W. Clark, Bruce Mate, Daniel Palacius, Robert Dziak, Sara Heimlich, Christina Connett, John Hildebrand, John Calambokidis, Ann Sirovic, David Cade, Roger Payne, Graham Burnett, Ann Allen, Kate Micucci, Michael J. Novacek, Vint Virga, Patrick R. Hof, Joshua Zeman (narrator), Bill Watkins (archive footage). Director: Joshua Zeman. Screenplay: Lisa Schiller and Joshua Zeman. Web site. Trailer.

Imagine having something to say, but no one is able to understand you. With no active dialogue or meaningful feedback involved, the “conversation” soon turns one-sided. And, if no responses are forthcoming any time soon, loneliness and sadness are bound to set in. The feeling of isolation this creates could easily become overwhelming. It’s a truly disheartening situation. But, in this case, this scenario isn’t describing something that one of us is experiencing; it’s an account of what might very well be happening to one of our fellows in the animal kingdom, as seen in the touching new documentary, “The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52.”

During the Cold War, the US Navy established an undersea tracking system to listen for the presence of Soviet subs, the Sound Surveillance System US (SOSUS). According to Joseph George, Retired Chief, US Navy, Integrated Undersea Surveillance System, in the process of listening for these vessels, the system began picking up the sounds of whale songs. These whale sounds were differentiated from those emanated by submarines based on variations in their signal frequencies, specifically their Herz levels. And, over time, with more listening, researchers were able to decipher differences in the frequencies produced by various whale species.

According to Dr. Christopher W. Clark, senior scientist at Cornell University, blue whales sing at a frequency of 100 Herz. Fin whales, by contrast, croon in a rhythmic pattern. And humpback whales, whose elaborate and prolonged songs are perhaps best known, have their own characteristic signature. But, in 1989, a signal was discovered that didn’t fit any of the established patterns, and it appeared to be coming from a single source. As this signal was seemingly the only source of any sounds on this unique 52 Herz frequency, researchers weren’t exactly sure what they had found. It was presumed to be coming from a whale, but it was unlike anything that had ever been discovered before, perhaps even a previously unknown species. In any event, this incident thus marked the beginning of the legacy of “52,” an apparently solitary whale that was somehow singing on its own frequency.

Several years later, oceanographer Bill Watkins isolated the 52 whale and tracked it for 12 years, plotting its migration pattern. But he never undertook a search for it prior to his death, given the unlikelihood of finding a single whale in such a vast expanse of ocean whose believed territory stretched from southern California to Alaska. And, considering that some whale species can cover as much ground as 2,500 miles in a single day, the search would be akin to looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack. Nevertheless, the discovery in itself was considered significant, and the creature was subsequently nicknamed “the Watkins Whale” in honor of the man who found it.

So what exactly was this Watkins whale? Could it be a hybrid, perhaps of a blue whale and a fin whale? Was it a new, previously unknown species? Or was it some other kind of oceanic anomaly altogether? Researchers over the years were curious to find out, but, realistically speaking, they understood the challenges involved, many of which recalled the sentiments expressed by Watkins himself. What’s more, since no one had been tracking 52 for many years, there was also a question about whether the creature was still alive. Even though a number of whale species can live as long as 70 years, there was no indication of how old 52 was when its vocal footprint was first spotted in 1989 and whether it could still be within its hypothetically projected life span. Yet researchers also conceded that perhaps alternative investigative practices could be employed to find 52; after all, they said, with whales, what we hear can often be more revealing than what we see.

As the foregoing illustrates, sound can be quite a telling indicator when it comes to whales. Those curious about looking for 52, notably filmmaker Joshua Zeman and a team of researchers, believed that the classified SOSUS information collected since 52 was last tracked could prove quite helpful to see if its signal had been spotted in the interim. However, for national security reasons, permission to access the data was initially denied. But assistance in obtaining this information soon came from an unlikely source. Robert Dziak, PMEL Acoustics Program Manager for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who studies underwater volcanoes using SOSUS data, was able to secure it to aid a new effort to find the Watkins whale.

After a review of the SOSUS data, NOAA scientist Sara Heimlich came across a pattern on the 52 Herz frequency where a signal appeared to be repeatedly emitted in 10-segment bursts. However, even though this may have been a calling card from the whale, the data was determined not to be specific enough. So, if researchers truly wanted to find it, they would have to go look for it.

An effort was thus launched to put together an investigative team. Since it was believed that 52 could be a hybrid of a blue whale and a fin whale (and that it could be travelling in pods made up of either or both of these species), the team sought out experts who were well-versed in their knowledge of these creatures. The investigative crew tapped the expertise of a number of scientists and oceanic specialists, including John Hildebrand, bioacoustics professor at the Scripps Institute for Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, and John Calambokidis of the Cascadia Research Collaborative. Calambokidis studied blue whales for 35 years and believed he once may have found evidence of a possible hybrid whale that might have been 52, though no sound data was collected at the time to definitively verify this conclusion.

A seven-day search was organized, conducted off the coast of Santa Barbara, California, a chief feeding/migratory path for blue whales, fin whales and humpbacks, 52’s most likely “relatives.” Investigators listened for these species with sonobuoys formerly used by the US Navy, and groups of blue, fin and humpback whales were tagged to see if they could lead the researchers to 52. It was believed that 52 could well have been alone in a whale community. It was also believed that other whales could hear it but couldn’t understand it because of its unique frequency, a circumstance that made 52 “the ultimate outsider.”

All of the interest in 52 naturally raised the question, why were researchers so curious about it? In many ways, this became a story where myth meets science. Many wondered, is the whale itself truly lonely? The question itself even began to be celebrated in story and song, a fable that somehow struck a chord with people, including those outside the scientific community. Many found themselves becoming sympathetic to the whale’s plight. How lonely it must be for that creature. But, then, given troubling developments in human society in recent years related to breakdowns in our own communication, listening and interaction practices, this sentiment somehow resonated with us. We could appreciate what 52 might be going through, because we had been going through it ourselves to greater and more disturbing degrees.

Cetacean researchers have found in their studies of whales and dolphins that these animals are highly intelligent. Neuroscience professor Patrick R. Hof, for example, says that whales have cellular structure in their brain physiology supporting this idea, as well as a sense of sentience and self-awareness. What’s more, animal psychologist Vint Virga observes that whales are also highly social beings as evidenced, for example, by the existence and structure of their communities. And, when one puts all of these ideas together, could that indeed make the case that 52 might genuinely be lonely? If we can sense that, and if we know firsthand what those conditions might be like, then perhaps there’s a viable basis for believing it to be true where the Watkins whale is concerned.

Obviously there’s more to this story than just a search for a scientific curiosity, even if the exact nature of the investigation is difficult to pinpoint. Perhaps it’s the search itself that’s what matters most. Maybe our quest to find 52 is a metaphor to find ourselves, especially when it comes to locating the parts of ourselves that are missing, filling voids that are desperately in need of being filled. Indeed, what we’re looking for and what 52 may be looking for could be the same thing, and that’s a concept we can relate to and identify with. If we can find 52, then maybe there’s a way we can help one another to give us and it what’s needed – and to overcome the oppressing loneliness.

The story of 52 is a touching one in many ways. It’s truly astounding how a film – particularly a documentary – can evoke such a genuine emotional response for a being that’s not a fellow human. But the parallels in our respective circumstances cry out for our attention, for the insights we glean from the whale’s story have benefits for us as well. And, when we come to believe that, we begin to realize that the creature’s experience could indeed be a cautionary tale for the rest of us.

Such beliefs, in turn, are important for the impact they have in shaping the nature of our reality, the outcome of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting our existence. If we can relate to the qualities that characterize 52’s situation, we can’t help but ask ourselves, do we really want to end up the same way? Do we truly want to live in a world where we’re unable to connect and communicate with others, especially when we seem to be unwittingly yet intentionally creating circumstances that bring about such a result? Indeed, perhaps we’re so drawn to this saga because we don’t want to end up living under the same conditions, and 52’s experience can help to make us aware of that possibility before it’s too late. It’s one thing to assert our individuality, but it’s something else entirely to do so by becoming loners.

There are a number of stories involving whales over the years that have helped or could be helping us to come to comparable realizations, several of which are addressed in the film. For instance, at one time, man hunted whales indiscriminately, bringing a number of species to the brink of endangerment or even possible extinction. But, as Roger Payne of the Ocean Alliance points out, once humanity was made aware of the intelligence of these creatures (thanks to the popularization of recordings of whale songs in the 1970s), we had a drastic change of heart. How could we possibly think about callously killing these beings? In fact, how could we realistically think about doing that to any of the other species that occupy this planet with us? Whales helped teach us that lesson, enabling us to change our beliefs and their associated outcomes, and we have them to thank for it. Indeed, as Payne put it, “When people care, they can change the world.”

Even if the foregoing enabled us to drastically change the course of history, that’s not to say we don’t still have work to do, and whales are again showing us what needs to be done. Oceanic sound pollution, for example, could be inhibiting 52’s ability to communicate with its kindreds, but researchers have come to discover that this is actually a growing issue for all whales. Sound distortions created by freighters, submarines and underwater explosions conducted to search for new oil reserves all lead to confusion for the whales, especially those whose feeding territories overlap with the areas from which these sounds emanate. This can cause such problems as whales being mutilated and killed when they become entangled with the propellers of boats they’re unable to avoid in time. This issue is thus depriving whales of their native habitats and their natural ability to communicate, and we’re responsible. These incidents could be aimed at helping to make us aware of the problem and enabling us once again to change our beliefs while we still have the chance, not only for the whales’ sake, but also a means to help preserve and protect our own environment.

As director Zeman observes, the relationship between man and whales hasn’t always been an easy one. This is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in Herman Melville’s famous novel Moby Dick, in which the obsessed Captain Ahab was determined to defeat his allegedly demonic nemesis, the great white whale, at any cost. But, as science has shown since the penning of that work, the notion that whales could be looked upon in that light is a huge fallacy, one of mankind’s greatest follies driven by ignorance and the beliefs that back it up. Now that we know more, however, we can drop those erroneous convictions and enable ourselves to embrace more enlightened principles like respect, tolerance and keeping an open mind until we know all the facts. In fact, Ahab’s experience illustrates the potential danger in falling prey to obsessions of any kind, not just those associated with recklessly killing whales. Yet this is another case where it’s taken a whale’s tale to help us come to that realization. (Who says these undersea creatures don’t know a thing or two?)

As the whales continue their work with us as teachers, there are other areas in which they can help us. For instance, 52’s tale is a key example when addressing our collective connection and communication issues, helping us mend the needlessly severed ties with our human tribe. But they can also work with us individually, helping us to learn personal lessons of great importance, depending on our particular interaction with them. In that regard, they can thus become mentors for us, enlightening us to heartfelt individual insights that can help us with our own personal growth and development, not unlike what the “kindly” tiny mollusk did for filmmaker Craig Foster in the Oscar-winning documentary “My Octopus Teacher” (2020). Perhaps 52, in its own way, is doing the same for us, both individually and en masse.

Perhaps the greatest takeaway for us from this film is that, in line with conscious creation philosophy, the world around us is a reflection of our inner selves. That includes all the creatures that share this reality with us, and our cetacean cousins’ presence is to help remind us of that. They reinforce the idea of connecting with one another, both among fellow humans and across species lines. They make clear that we must be responsible, accountable stewards of our environment (indeed, of the entirety of our reality as creators of it). And they show us, by way of the examples they set within their own pod communities, that we must all get along with one another if any of us hope to survive. Let’s hope we’re listening to more than just their enchanting melodies.

The search for connection is something that we all understand, not only as a social practice, but also as a personal and collective need, and this film effectively conveys that message. The mythology that has emerged about this enigmatic creature is thus more than just a sweet and sentimental tale, with insights that are clearly presented and shared in a thoughtful and straightforward, but by no means dogmatic, manner. The film also provides a detailed, captivating and beautifully filmed, though not excessively technical, account of the seven-day expedition to search for the cetacean social outcast. The picture’s sidebar stories are fascinating, too, even if often introduced somewhat awkwardly. The insertion of a number of somewhat self-aggrandizing observations from the director admittedly impedes the flow of the narrative at times, but the picture’s other strengths make up for this, especially its metaphorical parables that we had all better heed if we hope to save the whales – and ourselves.

After a brief theatrical run in early summer, “The Loneliest Whale” has since become available for streaming online. Viewers should be cautioned, however, not to confuse this offering with “Fathom,” another documentary about whales available for streaming that was also released over the summer – and did a far less successful job in telling its story. If it’s whales you’re looking for, 52’s story is the one to watch.

As much as humans like to think of themselves as the most advanced species occupying this world, it’s undeniable we still have much to learn, and the fellow residents of this place we call Earth obviously have much to teach us, as 52’s experience illustrates. We should be grateful for their presence – and their companionship – for joining us on this journey. Not only do they make it more enjoyable, but they also enlighten us, helping to make the world a better place for all of us.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment