“Straight Off the Canvas”(2020). Cast: Elizabeth Castellano, Jessica Jones, Sarah Valeri, Elizabeth Axel, Nicole Flores, Francis Rivera, Katherine Gelchinsky, the art students of the Lavelle School for the Blind. Director: Anthony Saldana. Screenplay: Jason Figueira and Anthony Saldana. Web site.

It’s easy to dismiss certain possibilities as being wholly impossible. But, as life has often shown us, that’s patently lazy, unimaginative thinking. The seemingly implausible can indeed occur with a little adjustment in outlook (and, of course, the accompanying logistics). So it is for a challenged but inspired group of creatives as explored in the uplifting documentary, “Straight Off the Canvas.”

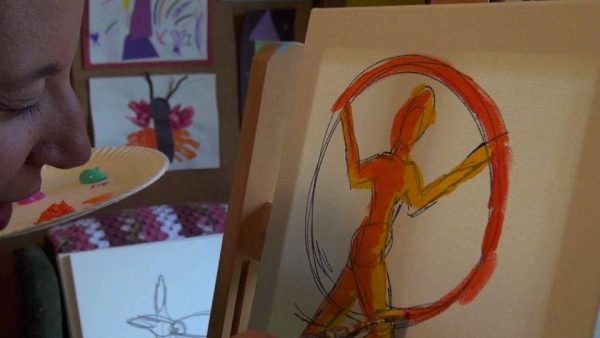

How many of us have given thought to the notion that blind or visually impaired individuals can become artists? How can they possibly “visualize” a finished product that they can’t see or possibly even envision it in the same way that the sighted do? It may seem completely unlikely, but, as director Anthony Saldana’s film illustrates, it’s not only possible but has indeed happened.

“Straight Off the Canvas” profiles a number of blind artists and art teachers who have succeeded in their odds-defying efforts. This material is supplemented by interviews with professionals and advocates who work with these creatives to help inspire them or to develop workarounds for issues that might present logistical problems. And the results are nothing short of amazing.

Elizabeth Castellano, for instance, is a painter and former art teacher who was born blind. She gained some sight with a corneal transplant as a teen, but her visual capabilities were still far less than a typical sighted person. Nevertheless, she was inspired by the drawings of her childhood friend Katherine Gelchinsky and was determined to follow suit, becoming something that most everyone thought she could never do. As she experimented with painting styles over the years, she learned after a time that her visual impairment could actually influence and even characterize her own form of artistic expression, one that’s more emotive than realistic. In fact, she admits, becoming too realistic in her work would expose the impairment and undermine her style’s inherent singular validity.

Jessica Jones is a teacher at New York’s Lavelle School for the Blind who majored in the arts in college, but she went blind as a result of diabetic retinopathy in adulthood. She carries on, though, showing other aspiring blind artists how to fulfill their potential. She says she gets the greatest joy out of art when she’s making items to be given as gifts or when she’s teaching others (especially visually impaired kids) to become artists in their own right.

As these artists and art therapist Sarah Valeri have discovered, though, some adjustments are needed to help aspiring painters live up to their potential. For example, when it comes to the concept of “color,” how does one express it only verbally? How does one who’s unsighted understand the difference between orange and purple? And how does one relate the idea to someone who can’t differentiate and/or perceive color in the same way as someone sighted? Valeri says it needs to be expressed as a feeling, not as a visual (or purely verbal) description. Comparing yellow to warmth or red to passion, for example, helps to convey these notions without ever seeing these hues firsthand. Similarly, creating a sample board of swatches of different materials helps to convey an awareness of different types of textures and the feelings they invoke, notions that can then be translated into artistic expressions.

According to Elizabeth Axel, creative director of Art Beyond Sight, bridging the gap between aspiring blind artists and a sighted world that takes its visual capabilities for granted is crucial to help these individuals fulfill their dreams. She stresses the need to overcome the limitations that the sighted community has set for what constitutes “visual art.” These assumptions need to be supplemented with notions that are more inclusive, making it possible for art to be understood and appreciated in additional ways. For example, “accessible” museums – those that encourage a more tactile experience of art – are an effective way of accomplishing this, offering tremendous therapeutic value for those who are blind and still want to be able to appreciate the qualities of art that the sighted enjoy.

As the film clearly points out, the foregoing illustrates some of the widely held misconceptions about what the blind are capable of. Drawing on a scene from D.W. Griffiths’s film “Orphans of the Storm” (1921), for instance, director Saldana shows how attitudes about blindness became rooted, established and reinforced in the thinking of the sighted world. Blindness, the Griffith film asserts, renders someone helpless, a condition equivalent to the powerlessness, vulnerability and dependence of a newborn baby. In addition to robbing the blind of their sense of personal empowerment, this outlook proved to be a damaging, close-minded notion for art, because it made art into something considered in visual terms only. And the visually impaired and their advocates have been battling that stigma ever since.

Would-be blind artists need to be reassured that there is no right or wrong when it comes to creating, assessing or appreciating art. Helping the visually impaired understand this draws attention to the importance of art therapy, a practice that connects the mental, emotional and physical aspects of art, creating a wholeness built on these traits and providing a safe milieu for expressing oneself. And, with suitable modifications and adaptations, limitations to achieving these goals can easily be overcome.

This also illustrates the importance of making adept teachers available to instruct artistic aspirants, a sentiment summed up in the film by a quote from visionary Albert Einstein: “It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge.” Good teachers are crucial to helping would-be artists becoming actual artists, a blessing that truly inspired Castellano to launch her artistic vocation and to become a teacher in her own right. This is especially true where blind art teachers are concerned, for they have the ability to inspire blind students, giving them someone to identify with. These teachers can draw from their own experience in telling their kids “You can do this.” What’s more, blind teachers aren’t limited to instructing blind students; those who are talented enough can effectively instruct the sighted as well.

In addition to these timeless themes, the film includes a segment rooted in contemporary conditions – the practice of art under quarantine. COVID-19 has impacted all of us in numerous ways, and it has imposed additional challenges upon those with special needs, like the visually impaired. When those conditions are added to the already-challenging circumstances that blind artists (and particularly blind child artists) must face, the importance of providing further adaptations to their artistic and teaching practices surfaces. As the artists in the film explain, art helps people cope with the conditions of the pandemic, especially during confinement. That’s especially true for students who are separated from their teachers and from one another under these conditions. Thus it has become critical to be able to adjust tactics as needed. But, then, as the film shows, that’s nothing new for the visually impaired.

The importance of art in our lives can’t be underestimated. Indeed, the need to create is essential to our existence – and that’s true for all of us. The personal value and self-worth that come from our individual artistic expression gives our lives meaning as contributors to the human condition – and as a calling card to let others know we’re here.

The very notion of a visually impaired individual becoming an artist may seem outlandish, even foolhardy. Yet here are examples of people who have said no to the naysayers. The fact that they have succeeded in their quests suggests that they’ve had visionary experiences in which they have overcome their handicaps to become practitioners of their art. Some would likely even go so far as to say that they don’t possess handicaps at all but that they’ve been imbued with special gifts to further distinguish their craft in their own singular ways.

Such is what happens when one believes in the possibility, the product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents. It’s unclear whether any of them, including the individuals profiled in this film, have ever heard of this school of thought, but it’s apparent from their output that they have become proficient in managing and mastering a number of its key principles.

For starters, they have been able to envision outcomes that would seem to defy most expectations. That’s a crucial starting point, for if they’re able to picture the destinations they’re seeking, it’s only a matter of time before the beliefs follow to make those outcomes happen. Indeed, if one can dream it, one can create it; all it takes is filling in some of the blanks that fall in between, backed by beliefs that suit those needs.

Perhaps the biggest challenge individuals in these circumstances must face is coming up with beliefs that overcome the limitations standing in their way. This will likely call for making necessary adaptations, which, in turn, may require regular thinking outside the box. However, since creatives often tend to deal with the unconventional, that shouldn’t be particularly difficult in most cases. The inventiveness and innovation that they employ in coming up with their finished pieces are often the same qualities that they can draw upon in solving the logistical problems that arise along the way. All they need do is tap into that mindset, and the necessary beliefs are once again sure to follow.

What’s perhaps most crucial for these artists is the example they’re able to set, not only for other blind individuals, but also for anyone seeking to become an artist. They inspire and motivate other aspirants, and they add beauty and creativity to a world very much in need of it (especially these days). That’s quite a contribution in itself. And, when we see what they can do, we might well forget that they’re starting from a position that’s more challenging than most of us would ever face.

“Straight Off the Canvas” is indeed an inspiring and educational offering, one that will surprise many viewers every step of the way. And, for that accomplishment, the film has won 13 awards in film festival and other competitions, taking home the prize every time it has been nominated. Director Anthony Saldana has compiled a fine film, one that he looks to promote as an instructional tool to help advance the cause of blind artists through screening licenses and DVD sales targeted at educational institutions, including universities, schools, museums and nonprofit organizations. It’s always heartening to see a picture that does more than just entertain, and this release does just that.

To find out more about “Straight Off the Canvas,” tune in to the September 16 edition of The Good Media Network’s Mission Unstoppable video podcast with host Frankie Picasso and yours truly. We’ll interview director Anthony Saldana to learn how the documentary came together and where he takes it from here. Catch us on Facebook Live at 1 pm ET by clicking here, followed by a recorded rebroadcast on YouTube.

It’s been said that “A thing of beauty is a joy to behold.” Considering how the works of these artists were created, that goes double here. And, thanks to this film, we have the opportunity to discover that for ourselves.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment