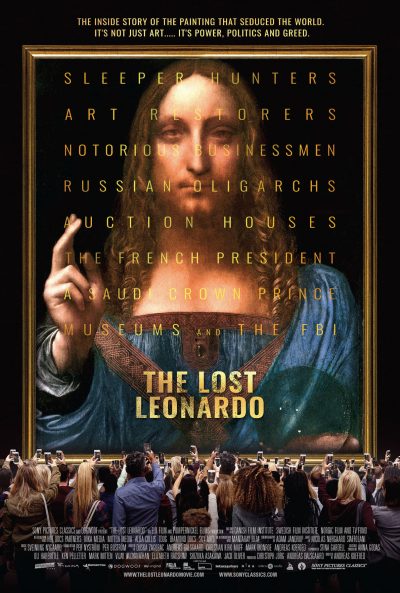

“The Lost Leonardo” (2021). Cast: Interviews: Dianne Modestini, Robert Simon, Alexander Parish, Warren Adelson, Yves Bouvier, Luke Syson, Martin Kemp, Maria Teresa Fiorio, Frank Zöllner, Jacques Franck, Evan Beard, Georgina Adam, Bradley Hope, Alexander Bregman, Kenny Schachter, Jerry Saltz, Stéphane Lacroix, Alison Cole, Antoine Harari, David Kirkpatrick, Robert King Wittman, Doug Patteson, Bruce Lamarche, Didier Rykner, Bernd Lindemann. Archive Footage: Mohammed bin Salman, Mario Modestini. Director: Andreas Koefoed. Screenplay: Andreas Dalsgaard, Christian Kirk Muff, Andreas Koefoed, Mark Monroe and Duska Zagorac. Web site. Trailer.

Art is one of the unique aspects of our existence that distinguish us as singularly human. It inspires us in myriad ways and helps give our lives meaning. In fact, it occupies such an esteemed place of importance in our reality that we often go to great lengths to ensure that its significance and value are sufficiently respected and venerated. But, when questions of legitimacy enter the picture, this process can turn dark, mysterious and even nasty, despite whatever good intentions and notoriety may be associated with it. Such was the case with establishing the authenticity of a high-profile, unexpected artistic find as explored in the engaging and entertaining new documentary, “The Lost Leonardo.”

Who would have thought that a painting could be capable of thoroughly captivating public attention? Nevertheless, such was the case with a work believed to be attributable to artist Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), the Italian Renaissance master considered by many to be the greatest painter of all time. And the story associated with this surprising find was itself a spellbinding tale, a mystery capable of challenging even the most astute sleuths.

The painting in question was da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi (Saviour of the World), a portrait of Jesus believed lost to time. Given the relative rarity of surviving works attributed to da Vinci, any painting believed created by the master has become a magnet for attention virtually by default. And, because no new finds have been made in ages, this unexpected discovery followed suit, especially since it is likely to be the last of its kind.

In 2005, art dealer Robert Simon and “sleeper hunter” Alexander Parish purchased the painting at an auction in New Orleans for $1,175. The mysterious portrait was in need of some restoration work, but suspicions were strong that there might be something of importance behind this find. But how legitimate were the claims?

Restoration work began shortly thereafter, with the task falling to art conservation professional Dianne Modestini. As she painstakingly undertook this daunting project, she grew ever more convinced that the attribution to da Vinci was legitimate. However, the more she worked on the portrait, the more restoration was required. At this point, the question began to be raised, “Was this a da Vinci or a Modestini?”

In the years that followed, the painting came up for considerable debate. Its legitimacy was hotly questioned by art critics, dealers, museums, auction houses and would-be buyers. Some were convinced it was authentic, while others said it a copy of a lost original. Others still believed it was a creation that came out of da Vinci’s studio, with work done by apprentices under the master’s supervision. Skeptics contended that, due to Modestini’s extensive touch-up work, verifying the picture’s authenticity was virtually impossible. And then there were those who vehemently claimed that it was an outright fake.

Nonetheless, despite this lack of consensus, interest in the Salvator Mundi remained strong, and it became the subject of a remarkable odyssey. It appeared in a 2011 blockbuster da Vinci exhibition at London’s National Gallery. It spent some time locked up in a freeport vault. And then it went through a series of attempted and completed sales. The Dallas Museum of Art sought to acquire the painting but was unable to raise sufficient funds. Next it was sold in a brokered private sale to Swiss businessman Yves Bouvier, who, in turn, sold it to Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev for a handsome profit, an exchange that led to high-priced ongoing litigation. But perhaps the most significant development in this chain of events was the 2017 sale of the portrait by Christie’s in New York, fetching a whopping $450 million, the highest price ever paid for a painting at auction. The buyer was officially listed as Saudi Arabian Prince Badr bin Abdullah, believed to be an intermediary for controversial Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

So where is the painting now? That’s unclear. A planned exhibition at the Louvre Abu Dhabi was indefinitely postponed in 2018. The painting’s inclusion at a 2019 da Vinci exhibition at the Louvre Paris also failed to materialize. These cancellations have thus raised questions about the portrait’s whereabouts and its security. Some reports have speculated it is in storage in Switzerland, while others have contended it’s aboard bin Salman’s luxury yacht in the Red Sea. Still other reports claim that the painting’s debut is pending, awaiting completion of the Al-’Ula cultural center in western Saudi Arabia.

In the course of its incredible journey, the painting has been at the center of mystery, intrigue and controversy, as well as an array of related ancillary considerations. It’s curious to see how a portrait of a religious figure has become tied up with such concerns as money, politics, litigation and personal credibility, as well as the integrity of the art world. It’s also ironic to see a painting of a Christian icon now in the ownership of Muslim royalty. It will be intriguing to see where events go from here, but, no matter what happens, they’re almost assuredly to be affected by considerations beyond the tangible – just as they have been all along, regardless of how apparent or unclear that may have been.

Those who embrace the notion of a Higher Power place their faith in that idea, often with all their heart. They unquestioningly believe in said being, phenomenon and/or concept for varying reasons. For some, it provides comfort. For others, it gives them some kind of context or a frame of existential reference into which they can place themselves. And, for others still, it affirms a sense of being, a kind of confirmation of oneself.

In all of these instances, that faith in a Higher Power relates to matters of a spiritual or metaphysical nature. However, not all notions of a Higher Power are restricted to these contexts. They can also apply to particular areas of life, imbuing them with an equivalent meaning and degree of power and importance. For sports fans, for example, one could look upon storied coaches as icons of their vocation. Likewise, car enthusiasts may view high-end automobiles as pinnacles of technology and craftsmanship to be admired and emulated. And, in the art world, the same could be said of great masters and their revered works.

Which is what brings us to da Vinci. To many, he’s an icon beyond compare, and the limited number of his surviving paintings makes their value – both artistically and monetarily – that much more compelling. So, naturally, when a suspected new find by the artist suddenly appears, interest in the work soars. And, for those who idolize da Vinci for who he is and what he created, there’s a hunger to want to verify the authenticity of a new piece, to find out if it can legitimately be added to a family of masterpieces that has achieved legendary status and whose very existence can be canonized, elevating it to the level of artistic sainthood. One could argue that such validation becomes even more significant when the subject matter of the work in question represents an esteemed religious figure like Jesus, one who not only personifies a spiritual apex, but whose depiction metaphorically symbolizes a comparably lauded embodiment in a secular milieu. So it is for Salvator Mundi.

However, for all of those who want – indeed, need – the painting to attain such veneration, there are those who have different agendas. Hard-core skeptics, for instance, demand concrete proof of authenticity before they’ll accept definitive attribution. Similarly, devil’s advocates are willing to play both sides of the fence and weigh the evidence before coming to a conclusion. Then there are the artistic agnostics, who are committed to remaining ever doubtful. And, in each of those cases, the respective proponents are firmly rooted in their convictions, believing what they know and feel in their hearts.

This, of course, raises the question, who’s right? Strange as it may seem, though, the answer is all of them.

And why is that? It comes down to a matter of beliefs, for they form the foundation of the faith we each place in our convictions. Beliefs are also significant in that they shape the nature of our existence through the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw on the power of these tools in manifesting the reality we experience. That includes the various components of our existence and what we each need them to be and/or represent. In the case of the painting, it’s an icon for those who need it to be one. For the diehard skeptics who assume it has it be a fake, it’s a fake. And so it goes for those who need it to take on other attributes and meaning.

In that vein, the painting thus serves as a metaphysical metaphor. While its physical qualities may be virtually identical for all concerned, the portrait’s nature and character vary from individual to individual. Each of those embodiments is equally valid, for they legitimately take their “forms” in the minds of those who’ve created them. It may seem paradoxical that “one” item can stand for so many different viewpoints, yet that’s what each proponent has manifested based on his or her individual beliefs, and they’re each “right” in their regard, no matter how implausible that may seem.

Understanding this is important not only for grasping the meaning of the painting, but also because of the example it provides in enlightening us to the nature of how the totality of our reality unfolds in all of its particular components. If one can grasp the idea behind this example, one should be able to appreciate how it applies to everything we create and all that we encounter in our respective realities. It thus sheds light on a fundamental principle of how existence operates. It’s also intriguing that it has taken a portrait of Jesus to enlighten us to this, but, then, that’s another set of beliefs entirely.

The fact that the painting has been part of such a remarkable odyssey suggests that its journey has involved more than just making the world aware of a brilliant piece of art. It’s almost as if it has been involved in helping to spread the word of these principles to a world in need of hearing them. Whether or not the message has gotten through is a different matter, but, if nothing else, it represents an undertaking to get these ideas out to those hungry for answers. This film furthers that cause by telling a captivating mystery tale, one that, hopefully, attracts sufficient attention. Indeed, we can only hope that, in the end, the underlying message doesn’t become lost – or fall on deaf ears.

Traversing the landscape of mystery and intrigue associated with this painting no doubt had to be a confounding experience, yet director Andreas Koefoed has pulled off quite a feat of sleuthing and filmmaking in creating this captivating offering. The carefully crafted screenplay tells its story clearly and concisely, but it does so by showing its hand sparingly, preserving the sense of playful inscrutability as the narrative unfolds. The panel of experts assembled for the film presents viewers with an array of insights, from the devoutly reverent to the unabashedly incredulous, all the while spinning a yarn filled with financial and geopolitical gamesmanship, art world skullduggery, and even hints of tongue-in-cheek whimsy. The film has been playing in limited theatrical release, with wider distribution pending.

In an age when it’s become increasingly difficult to tell the difference between what’s true and what’s not, the discovery of an alleged missing masterpiece takes on new relevance, in many ways coming to serve as a prime example of this baffling conundrum. And, because of that, when “facts” fail us, all we have left to fall back on is our beliefs. But, as this documentary so poetically illustrates, they’re arguably more important in light of the role they play in shaping our reality. It’s a message that we need to embrace at a time when we need something to help ground us, as well to uplift us, especially given the subject matter of the painting. Perhaps we each need to find our own Salvator Mundi, and the ideal place to start is within us, searching our beliefs to find ourselves, our reality and our own source of salvation.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment