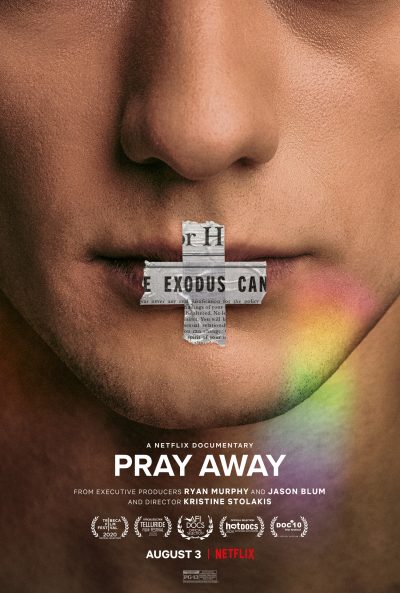

“Pray Away”(2021). Cast: Interviews: Julie Rodgers, Randy Thomas, Yvette Cantu Schneider, Michael Bussee, John Paulk, Jeffrey McCall, Diana E. Wright, Alan Chambers. Archive Footage: Joseph Nicolosi, Ricky Chelette, Anne Paulk, Jerry Falwell, James Dobson, Lesley Stahl, Jerry Springer, Lisa Ling, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Karl Rove, Newt Gingrich. Director: Kristine Stolakis. Web site. Trailer. Producers’ Discussion. Video Clip.

Attempting to be something that one is not is a perilous course in so many ways. It means fundamentally going against oneself, denying one’s true nature. The lack of authenticity and integrity in such scenarios is not only disillusioning, but it’s also potential damaging, again, in countless ways. So it was for thousands of individuals who underwent a controversial treatment program as depicted in the gripping new documentary, “Pray Away.”

The LGBTQ+ community has made remarkable strides over the past several decades. This once-disparaged constituency has come a long way thanks to legislation, court decisions and corporate initiatives that have led to broader legal protections and greater social acceptance.

But it wasn’t always that way; prejudice and discrimination were once rampant, and members of the community were often made to feel like second-class citizens. The oppression was so prevalent and intense, in fact, that it often led to individuals being disowned by their families, excommunicated by their religious organizations and fired by employers. Such measures wore heavily upon many of those affected, prompting them to detest themselves and their own sexuality. Some even went so far as to attempt or commit suicide. Many, however, chose another, seemingly less drastic path; they sought to rid themselves of what they saw as an unbearable scourge upon themselves, pursuing a controversial form of treatment known as “conversion” (or “reparative”) therapy, the subject of this documentary.

The idea behind this form of “treatment” was that one could use it to turn away from homosexual tendencies, leaving them behind to become full-fledged, card-carrying heterosexuals. Those who abhorred their feelings of same-sex attraction frequently saw this as a viable means to overcome drives and emotions that made them uncomfortable in their dealings with family, friends, co-workers and fellow religious congregants, not to mention with themselves. And, thanks to polished, compelling recruiting efforts, packaged with promises of happiness and an end to suffering, the proponents of this program successfully attracted many followers who sought to implement this fundamental change in their lives.

Conversion therapy got its start in the 1970s. One of its early proponents was Michael Bussee, a gay man distressed by what he believed were unnatural feelings. At the time, he saw that support groups were being established to help challenged individuals cope with a variety of conditions, such as alcoholism, drug addiction and domestic abuse. Bussee proposed that something similar could be launched for those experiencing the kind of anguish he was undergoing, and so he helped found a support group for would-be ex-gays through his church. Not long thereafter, he learned that similar groups were being established by Christian fellowships across the nation, and he proposed that they join forces. It was with that suggestion that a national umbrella organization known as Exodus was born in 1976.

Like the individual support groups that preceded it, Exodus was rooted in traditional Christian theology and principles. The conversion therapy program that subsequently emerged was designed to help would-be ex-gays identify how they developed their homosexual leanings, how they could overcome those feelings and how they could then move on to idealized heterosexual lives based on the nuclear family concept. Through a combination of counseling, group encounters and devout religious practice, it was believed that program participants could essentially “pray away” their supposedly errant views. The program sounded reasonably plausible to those who sought it out, especially when it received the scientific backing of professionals like clinical psychologist Joseph Nicolisi, whose support Exodus welcomed for the “legitimacy” it gave to their claims. There was just one problem with all this – it didn’t work. In fact, over time, in many cases, it actually ended up doing more harm than good.

Why didn’t it work? Basically it was an effort aimed at forcing individuals to become something they innately weren’t. To make matters worse, most of the program’s facilitators had no formal training in in psychology, counseling or human sexuality. Yet, because they had the apparent force of God behind them, they frequently came across as having all the answers, often with a heavy-handed attitude contending that they spoke for Jesus and that their “wisdom” was not to be questioned. Participants who had difficulty conforming were made to feel like failures, even shamed for the slightest “transgressions.”

Still, despite the fear and intimidation that frequently accompanied involvement in these programs, many individuals hoped they might somehow miraculously work and that their teachings would eventually enable better relations with those who ridiculed them. Indeed, the lure was strong enough to attract an estimated 700,000 participants to its ranks. Sadly, many participants were left worse off than before they started. This was particularly true for at-risk gay youth who were forced into treatment, often by their own families. According to statistics presented in the film, such individuals were twice as likely to attempt suicide as a consequence of their participation.

The film takes a close look this form of “therapy” over the years. It also follows the stories of a number of former participants, as well as one individual who is still actively involved. Director Kristine Stolakis details how and why these onetime advocates – known as “ex-ex-gays” – became engaged in this movement, what they did while active in it, what prompted them to leave and what they have done since then. In virtually every case, the film paints a picture of a woefully ineffective, if not outright dangerous, practice that has proved to be more harmful than beneficial.

The individual stories are perhaps the most gripping elements of the film. For instance, there’s the experience of John Paulk, an articulate, high-profile Exodus spokesperson who married a former lesbian and was hired to essentially be the organization’s poster child. He played the role for a number of years, often struggling against feelings he could not contain nor hide. When his wife, Anne, herself an ardent spokesperson for the cause, learned of this, she flatly asked him, “Why can’t you just obey?” Paulk eventually resigned after fleeing photographers as he exited a Washington, DC gay bar. He later said he had to figure himself out, because, if he didn’t, he would take his own life.

Other leaders in the movement experienced comparable issues. Yvette Cantu Schneider, for example, sought sanctuary through the ex-gay community after losing many friends in the early days of the AIDS crisis. What started out as a source of comfort turned into a dogmatic platform for her through her involvement in Exodus and as a policy analyst for the Family Research Council, a conservative Christian lobby. She eventually became a major proponent for the passage of California’s controversial Proposition 8 in 2008, a voter-approved initiative that strictly defined marriage as an institution between one man and one woman, a hedge aimed at slowing the momentum of the growing same-sex marriage movement. The passage of Prop 8 subsequently led to Cantu experiencing PTSD-like panic attacks, prompting her into counseling sessions with a psychologist and eventual resignation from the movement.

The rise of the ex-gay movement politically during the George W. Bush administration caused considerable anguish for other movement leaders, too. Like Cantu, Exodus Vice-president Randy Thomas campaigned for the passage of Proposition 8, an effort that left him overcome with guilt in its wake. He was troubled when he watched televised gay protests in the streets of San Francisco afterward, leading to soul-searching in which he tearfully had to ask himself, “How could you do that to your own people?”

That sense betrayal against one’s tribe also affected Julie Rodgers, who idealistically came out as a teen despite a strong, traditional Christian upbringing. It was a decision that did not sit well with her family. She was subsequently encouraged to seek loving support and protection from the influence of “those dangerous gays” she had been cautioned about in her youth. She joined Living Hope, an Exodus affiliate led by Pastor Ricky Chelette. As an organization that touted itself as having “the path to be good,” Rodgers found comfort in the organization, especially when Chelette groomed the charismatic advocate to be Living Hope’s “next big thing.” But, over time, her self-denial of her personal truth led her to start engaging in acts of self-mutilation and intentionally burning herself, especially when she realized that she was preaching a message that was psychologically and emotionally damaging others in the same way she was injuring herself. She, too, exited the movement when she understood the harm she was causing.

Despite the resignation of these onetime leaders, others continue to promote the conversion therapy movement’s agenda, such as Jeffrey McCall, founder of the Freedom March, a group committed to promoting and reinforcing the ex-gay message, especially to millennials. He claims it saved him from a life of sin that would someday prevent him from accessing the kingdom of heaven unless he changed his ways. He has managed to court a core of followers by taking his Christian message to the streets, even seeking the support of those officially unaffiliated with the ex-gay movement.

Over time, though, the ex-gay movement has seen much of its momentum dissipate, especially with the 2015 Supreme Court decision removing restrictions against same-sex marriage. But cracks in the movement were apparent long before that. Even Exodus co-founder Michael Bussee could see that as early as 1979, just three years after the organization’s founding, when he resigned because he could no longer abide by its core message. An even bigger blow came in 2013, when Exodus president Alan Chambers formally oversaw the dismantling of the organization. That decision came in the wake of an intense televised group encounter session, hosted by journalist Lisa Ling, that brought together conversion therapy survivors and leaders of the ex-gay movement, including Chambers. Survivors confronted their former peers and facilitators directly, gut-wrenchingly expressing the pain that conversion therapy caused them. It was the nail in the coffin for an organization that, in all good conscience, could not continue to carry on promoting ideas and a form of therapy that was fundamentally harmful.

While the tide appears to have turned where reparative therapy is concerned, this controversial treatment has wreaked considerable havoc and left a trail of destruction in its wake. The time for healing has indeed begun, and the work ahead is considerable. However, healing is possible, and new beginnings are attainable for those who endured this ordeal. To get there, though, survivors must understand the nature of their experience and why the proposed solution came up so short of expectations.

Conversion therapy’s failure to “work” can be attributed to a fundamental false assumption – that there was anything in need of “fixing” in the first place. Those who participated in the program, either voluntarily or by coercion, came to believe that their supposedly “sinful” behavior led them to be “damaged” in some way. And, ironically, through their participation in the program, damaged is exactly how they ended up, even if they weren’t that way when they started. Those individuals weren’t troubled by being gay; they were troubled by the ways others treated them for being gay, a state of mind they ultimately internalized and embraced, leading them to believe that they were inherently flawed and in need of help from those who claimed to know how to repair them.

These circumstances illustrate the power of beliefs, particularly when it comes to how they shape our existence. This is a product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these tools in manifesting what we experience. And, when it comes to this unfortunate scenario, countless unwitting participants fell prey to the claims of these peddlers of deception, who planted seeds of belief that sprouted in the mindsets of so many vulnerable individuals.

It’s sad that so many program participants were unable to see that there was nothing intrinsically wrong with them in the first place. But, by erroneously adopting beliefs to the contrary, they launched themselves into a sequence of events that only compounded their distress. Even though proponents of the treatment claimed to abide by the notion of “hate the sin, not the sinner,” their actions often contradicted that idea, laying the blame back on the “sinners” and causing them further pain and confusion through the embrace of faulty beliefs, constructs that took root and didn’t let go. Such persistence, which is often typical of beliefs in general, made the journeys of these individuals that much more difficult until they were able to come around and understand their personal truths in the first place. Until that happened, though, there was often considerable more anguish to be borne in the interim.

The bald-faced dishonesty involved in trying to convince participants of “the errors of their ways” was generally attributed to what appeared to be reasonable causes. Individuals were taught that they became gay because of various traumas that occurred in their youth – abuse, bullying, molestation, toxic parenting and so forth. And, even though many participants may have experienced such indignities, it’s unlikely that they were the cause of them becoming gay but were, in fact, the reactions of others toward them for being gay. Nevertheless, the arguments were made convincingly and routinely enough to persuade participants otherwise, and that persuasive repetition was enough to get them to capitulate to the dictates of program leaders.

As the experiences of Cantu and Rodgers point out, many who engaged in this undertaking were wounded souls who needed comfort, and they hoped they would find it through communities like Exodus and Living Hope. However, once involved, the hoped-for outcome didn’t pan out; in fact, it was just the opposite. The experience made them jaded, embittered and judgmental, albeit euphemistically, prompting them to turn against others who were fundamentally kindred spirits, not to mention themselves. Over time, the pain of embracing beliefs that went against themselves mounted, eventually becoming overwhelming and leading to side effects that ultimately pushed them over the edge to remove themselves from continued participation. The debilitating pain of physical effects – some deliberately self-inflicted – as well as the escalating emotional impact, were bad enough, but the activists’ subsequent resignation from the movement only made their circumstances worse when they realized that they also lost their community and support network, no matter how wrong-headed their ideology may have been.

Ironically, many survivors found hope through the embracing love of Christian congregations, fellowships of individuals who accepted them for who they were without judgment. Those lost souls finally redirected their beliefs to help them find what they were looking for in the first place. The genuine, heart-based feelings such involvement generated gave these recovering victims hope and sanctuaries for healing. This led to restored hope, faith and an awareness, at last, that they were fine as they were and in no need of being “fixed,” save for whatever damage they suffered through their experience with conversion therapy.

Those who still cling to the alleged virtues of this “treatment” view ex-ex-gays as pariahs, and they have gone on to establish new organizations, such as the Restored Hope Network, an outgrowth of Living Hope. But many of the survivors have gone on to become strong vocal opponents of reparative therapy, part of a growing and powerful support network for themselves and their peers. Those who were once leaders of this movement fully understand that they have blood on their hands for the tyranny of rationalization and denial they inflicted on their former followers, pain and anguish born out of the undeserved shame they were made to feel. These onetime advocates feel the crushing weight of the harm they caused, and they generally believe there’s no redemption for what they did in pushing an outright lie about how their followers could become whole and healthy by trying to be something they couldn’t possibly be. However, given the power of beliefs, there’s no telling what these former activists might be able to create for themselves. Perhaps the story of the Prodigal Son might give them some insight into what beliefs they should consider employing for themselves.

One of the most noble endeavors that documentary filmmaking can pursue is the exposure of reprehensible behavior. So it is in director Kristine Stolakis’s debut feature, a damning indictment of the practice of conversion therapy. The filmmaker holds little back in shining a bright light on this horrific and unenlightened way of looking at life. Watching this film should rightfully infuriate anyone – gay or straight – for the unspeakable emotional atrocities perpetrated by this movement, which is neither helpful nor effective nor even Christian. This offering premiered on the film festival circuit earlier this year and is now available for streaming on Netflix.

The challenges we face in life are often difficult enough in themselves that we don’t need to have them compounded by additional ancillary considerations. Regrettably, situations like this often arise when we’re unable or unwilling to accept ourselves for who we are, believing that we’re somehow inadequate or unworthy, especially in the eyes of others. But, as difficult as such scenarios can be, they can be made that much worse if we allow ourselves and our attention to be diverted in other directions that only complicate matters and try to push us to be who we’re fundamentally not. While the perils of conversion therapy are patently deplorable, we can only hope that those who endured it have provided others facing similar circumstances with the wisdom and insights necessary to take them down different paths – and to avoid the unspeakable suffering and torment that they underwent.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment