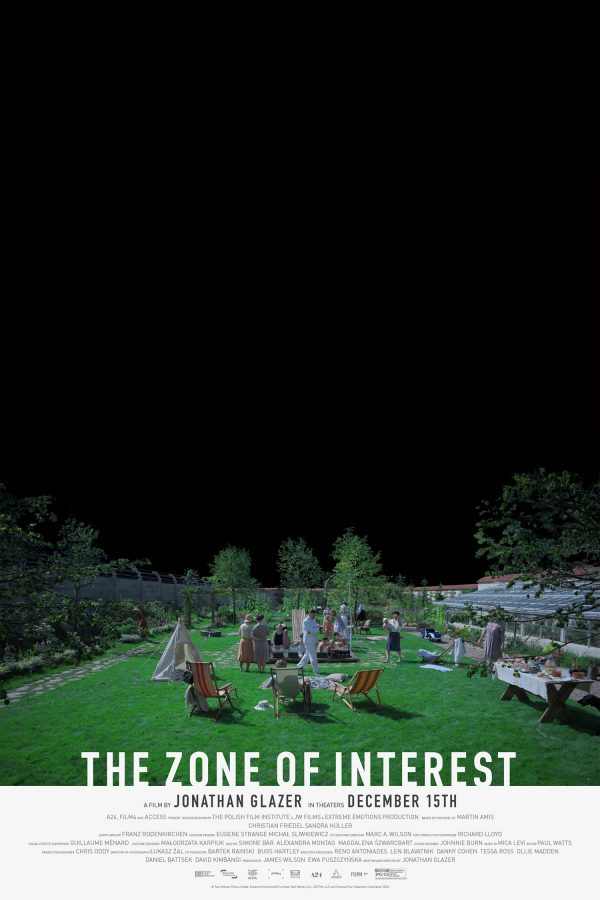

“The Zone of Interest” (2023). Cast: Christian Friedel, Sandra Hüller, Johann Karthaus, Luis Noah Witte, Nele Ahrensmeier, Lilli Falk, Anastazja Drobniak, Cecylia Pękala, Kalman Wilson, Imogen Kogge, Stephanie Petrowitz. Director: Jonathan Glazer. Screenplay: Jonathan Glazer. Book: Martin Amis, The Zone of Interest (2014). Web site. Trailer.

The most infamous of these concentration camps was located at Auschwitz in occupied Poland. With no offense intended here, the facility was run like a factory, where “efficiency” was considered an exalted objective. This was a goal overseen by the camp’s commandant, Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), who resided with his family in a compound immediately adjacent to the facility, separated by a dividing wall. There was a tremendously ironic dichotomy in this setup; while unrelenting death and revolting inhumanity characterized life in the camp, the residential compound was the seeming epitome of normality. In fact, the commandant’s wife, Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), saw the residence as the ideal place for the family, including the couple’s five children. Hedwig looked on it as the home she always wanted, her own version of paradise. She took pride in the garden she established, complete with flower beds, vegetable plantings and a greenhouse, along with a wading pool and play sets for the children.

In adopting this attitude, however, Rudolf and Hedwig were oblivious to what was transpiring just beyond the compound’s wall, despite the recurring sounds of gunshots and the incessant billowing smoke coming from the camp’s mass crematoriums. What’s more, they intentionally ignored smoking gun evidence of the camp’s atrocities that they encountered during their daily routines. In fact, Hedwig and the children matter-of-factly took pleasure in whatever valuable possessions they were able to acquire as a result of confiscations from camp victims, such as a full-length fur for mother and extracted gold teeth for the youngsters to play with.

Indeed, it’s astounding how the members of the Höss family could be so deliberately indifferent about what was going on around them. It’s truly mind boggling how they could so thoroughly compartmentalize their thinking and place their own needs, wants and desires before all else. Yet there they were, living their lives as if nothing untoward was unfolding in their midst.

In telling this story, the film is not focused so much on its narrative as it is on conveying the prevailing attitudes of its characters. In that sense, then, “The Zone of Interest” relies more on presenting a series of events reflective of those individuals’ perspectives, an approach that could be seen as somewhat episodic. Nevertheless, that tactic works, as those individual events collectively combine to paint a picture of the outlooks of its principals, one that’s quite chilling for viewers to witness. On top of that, the film never incorporates imagery that’s graphic or gratuitous of what’s unfolding in the camp; instead, the audience is shown preludes to, or evidence of the aftermath, of those events, a technique designed to further enhance the disturbing impact of what’s transpiring over the dividing wall.

Because of this, much of this release presents depictions of everyday events in the lives of the family. While some might see this as rather mundane, it’s nevertheless quite telling and keeps in line with the film’s central message. Certain incidents are particularly compelling, such as the reaction of Hedwig’s mother (Imogen Kogge) to what she witnesses when she comes for a visit, especially when the truth of what’s happening sinks in. Then there’s the indignance of Hedwig when she learns that her husband is about to be transferred to another Nazi facility in Oranienberg near Berlin, a move she strongly protests because she doesn’t want to leave the home she so dearly loves, even prompting her to defiantly stay behind despite her husband’s relocation. Again, one can’t help but wonder how people could behave in such an unfeeling manner.

Yet, the film’s unconventional approach notwithstanding, that’s precisely the point behind this picture. With so much brutality and barbarism taking place, it’s unfathomable that people could so easily look the other way and place their own interests ahead of those of the victims. That’s a powerful message that we should all take to heart, no matter what the circumstances and regardless of how great or small the consequences might be.

Of course, how we react to conditions like these depends greatly on what we think about them, specifically when it comes to our beliefs. And that’s crucial considering that our beliefs play a pivotal role in the manifestation of our existence, a result of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that governs how such materializations come into being. It’s not apparent how many of us are aware of this school of thought, but its impact can be substantial, for better or worse, particularly when viewed in light of the deliberately disregarded beliefs exhibited by the characters in this story.

Such shocking behavior and the beliefs that drive it reflect another significant consideration – an unwillingness to accept responsibility for what’s transpiring. In essence, by employing our thoughts, beliefs and intents in manifesting the reality we experience, we’re also inherently responsible for what emerges. However, given what unfolds here, it’s apparent that the characters have completely abrogated any accountability they might have in connection with such developments. In fact, there’s evidence of the exact opposite, such as when Rudolf meets with contractors on ways to make the functioning of Auschwitz more “efficient.” That speaks not only to an innate lack of responsibility, but also to a deliberate attempt at bringing about the despicable outcome that arises. How positively horrific. And that’s something we all need to bear in mind when we seek to create what our beliefs are aimed at manifesting.

One might wonder how individuals like Rudolf and Hedwig can simultaneously be so cruel and indifferent, on the one hand, and yet so lovingly and caringly devoted, as seen in their interaction with their family, on the other. It’s as if the various beliefs they hold are somehow deliberately walled off from one another in their consciousness, a means to bring about such incredibly divergent thoughts and manifestations at the same time. This kind of compartmentalization takes work to put into place, but they’ve managed to find ways to bring about such an outcome. It’s also difficult to imagine how they can manage to maintain such intentional separation of their various thoughts and beliefs. That takes tremendous energy and effort to pull off, sustaining a façade that even they must find difficult to support, especially in dealings with others, as evidenced by Hedwig’s interaction with her mother when she realizes the truth about what’s occurring next door. This is clearly a case of trying to play both sides of the fence – literally and metaphorically – and, in the end, it’s cowardly, ghastly and unconscionable.

Again, one can’t help but wonder how anyone could rationalize such thinking. The answer to that lies with the attitudes of many Nazi operatives during the war, who, after the conflict, attributed their behavior to the notion that “I was just doing my job,” as if that could somehow justify their actions. This concept perhaps became best known with the 1963 publication of the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by philosopher and political observer Hannah Arendt. The author drew upon and subsequently popularized the expression “banality of evil” to describe how Third Reich authorities like Adolf Eichmann – one of the architects of the Holocaust – explained their role in this atrocity. When Eichmann was put on trial for war crimes in Jerusalem in 1961, his defense was primarily based on the foregoing assertion, the same kind that many of his colleagues – like the characters in the film – would use to justify their actions, a contention that prompted Arendt to use her now-famous phrase for encapsulating its nature.

In her book, Arendt observed that Eichmann (and individuals with his mindset) weren’t fanatics or sociopaths. Rather, they were average individuals who fell back on this “banal” reasoning to describe the nature of their intrinsically evil actions. Incredibly, that’s what viewers witness in this film when it comes to the perspectives of individuals like the commandant and his wife, among others. And “The Zone of Interest” provides a poignant and chilling illustration of the beliefs and thinking behind the banality of evil at work, an observation that has been widely noted in many discussions about this film. Most of us would undoubtedly consider this attitude a feeble excuse for rationalizing such despicable behavior, yet these actions nevertheless arose out of the beliefs that these characters held – beliefs that ultimately became all too real for all concerned, especially the victims.

Despite the horrendous nature of what was manifested here, these unspeakable materializations nevertheless illustrate the sheer power of our beliefs and what they can be employed to do. One would hope that we would put such power to use in far more benevolent endeavors, such as the acts of compassion described earlier. But, for whatever reason, there may still be some among us who must see for themselves just how horrifically our beliefs can be employed just to see how powerful they truly are. It’s heartbreaking that such incidents have – and, in some cases, continue to be – brought into being for such unaware individuals to witness that notion in practice. We can only hope that we collectively learn that lesson sooner rather than later so that we can finally and genuinely proclaim “Never again.”

Some movies just have to be seen, even if they make for a difficult watch, and writer-director Jonathan Glazer’s latest is one of those pictures. While this offering is at times a bit uneven, when it’s on, it’s on, leaving a powerfully indelible mark on viewers, one that you feel in your gut and your heart and can’t get out of your mind. Mercifully, Glazer doesn’t resort to unwarranted grotesque imagery to make his point here, yet the subtly depicted outcomes of such savagery are just as quietly disturbing, a profound implementation of “Hitchcock’s rule” in which the filmmaker allows the audience’s imagination to take over and leave an impression more haunting than anything that can be captured on celluloid, a tactic widely employed in the films of the famed auteur. As troubling as this is, however, it’s the kind of imagery that has to be seen for its full impact to sink in. “The Zone of Interest” richly deserves the attention it has garnered, even if it’s an inherently disturbing watch (sensitive viewers take note), in many ways eerily on par with other films about the Holocaust, such as “Sophie’s Choice” (1982) and “Schindler’s List” (1993). To be sure, there are some pacing issues that could stand to be rectified, and a few story threads could use better clarity, but the picture’s superb cinematography, production design, original score and performances by its excellent ensemble cast (especially Hüller, who deserves greater awards season recognition for her portrayal in this film than in her more widely nominated role in “Anatomy of a Fall” (“Anatomie d’une chute”)) are undeniably noteworthy. This might be a film that no one wants to screen – but that everybody nevertheless should.

As unsettling as this film may be, though, its cinematic achievements are extensive and have been lavished with praise during the current awards season. For starters, it’s the recipient of five Oscar nominations for best picture, international feature, sound, director and adapted screenplay. Likewise, it has garnered nine BAFTA Award nods for best British film, international film, director, adapted screenplay, supporting actress (Hüller), cinematography, editing, production design and sound. This release also captured accolades from the National Board of Review (Top 5 International Films), the Critics Choice Awards (best international film nominee), the Independent Spirit Awards (best international film nominee) and the Golden Globe Awards (nominations for best dramatic picture, international film and original score). Perhaps its greatest recognition, however, came at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, where it earned a nomination for the Palme d’Or (the event’s highest honor) and won four awards (Grand Prize of the Festival, the FIPRESCI Prize, the CST Artist – Technician Prize and honors for best soundtrack). That’s quite an impressive resume for a film with such a difficult but affecting message. “The Zone of Interest” is currently playing theatrically.

It may be impossible to undo the past, but that doesn’t mean it should dismissed, either, and events like the Holocaust are among those that we must not forget. Films like this make that possible, but, perhaps most importantly, they shed valuable light on how and why they may have occurred, particularly when it comes to the attitudes that helped sanction them. And, when we examine the outlooks depicted here, it reminds us of our need to remain cognizant of what they were and how they arose. Diligence in the face of indifference is critical to prevent such horrors from recurring and sparing mankind from what should never have happened in the first place – and that certainly should never happen again.

Copyright © 2024, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment