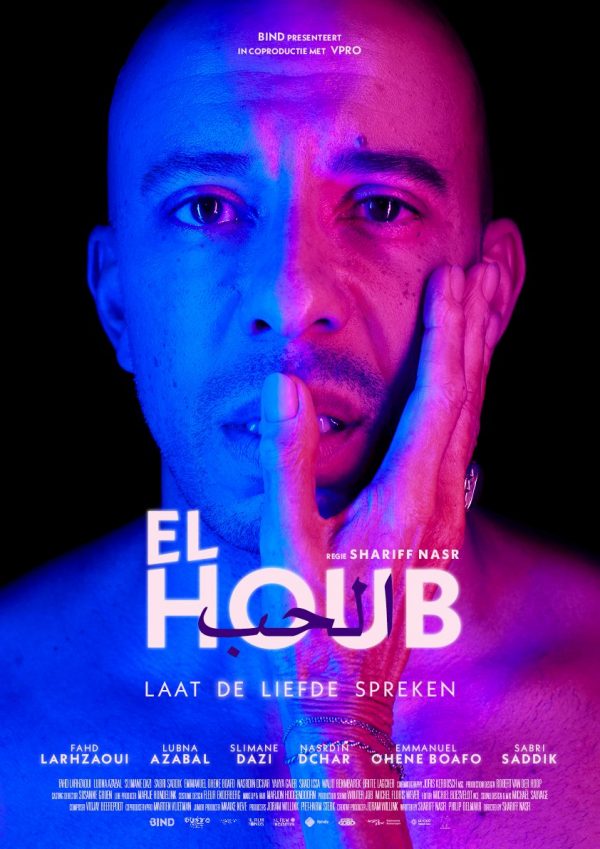

“El Houb” (“The Love,” “Laat de liefde spreken”). (2022). Cast: Fahd Larhzaoui, Lubna Azabal, Slimane Dazi, Sabri Saddik, Yahya Gaier, Emmanuel Ohene Boafa, Britte Lagcher, Nasrdin Dchar, Shad Issa Abdullah, Mahjoub Benmoussa, Walid Benmbarek, Esma Abouzahra, Rayan Berlhazi Alaoui. Director: Shariff Nasr. Screenplay: Shariff Nasr, Philip Delmaar, Fahd Larhzaoui, Tofik Dibi and Sahil Amar Aissa. Web site. Trailer.

As much as Karim loves his family, their conservative Muslim religious and cultural outlook flatly rejects anything that even hints at same-sex partnerships, which has forced Karim to keep silent about this part of his life. But that’s become increasingly difficult for him now that he’s become romantically involved with a loving boyfriend, Kofi (Emmanuel Ohene Boafa), an open Ghanaian immigrant who walked away from his family (and virtually anyone else he knew) who refused to accept him for who he is. The disparity in the duo’s outlooks on this matter has put a strain on their relationship, too, given that Kofi wishes Karim could be as free in being himself as he is, a disconnect that threatens their future together. Still, Kofi remains hopeful that Karim will come around to his way of thinking, though preferably sooner rather than later.

That question gets called a lot sooner than Karim was expecting. Early one morning, Abbas pays a surprise visit to his son’s apartment, where he finds Karim and Kofi together not long after they wake up. Abbas turns heels and departs as Karim anguishes about what to do next. Obviously he’s going to have to deal with this dilemma now. But how?

Shortly thereafter, Karim visits his childhood home, the modest apartment where he grew up after his family immigrated to the Netherlands. He’s met with a mix of emotions, from blissful ignorance to utter outrage. Fatima and Abbas initially engage in willful denial about this new revelation, but they soon turn angry when Karim openly raises the subject of his visit – to clear the air. They lament how he could possibly behave in what they see as such a dishonorable, heretical manner, one that they believe will bring disgrace upon the family, a classic “what will the neighbors think” reaction. They argue, and Karim makes a valiant effort to bring them around to his view, but the effort goes nowhere. And so, in a drastic attempt to get their attention and to force them hear him out, he resorts to a tactic that his younger self (Shad Issa Abdullah) often did during parent/child confrontations – locking himself in the utility closet, an ironic gesture but one that seriously gets their ear. And, before long, the ante gets further upped when he begins shutting off the utilities – first the water, then the cable television and finally the electricity. Forcing their hand, he hopes, will finally help to bring about resolution.

Through the closet door, they continue debating the issue. Karim struggles to get them to understand his viewpoint and to see that he’s just as deserving of acceptance as anyone else. He fights with Fatima. He fights with Abbas. And he has some especially scathing bouts with Redouan, whose spiteful tone seethes with unbridled hatred and blatantly homophobic barbs. It’s an ugly scene for all concerned, to be sure.

When arguing gets the parties nowhere, they begin resorting to other tactics. Abbas, for example, calls the local imam (Mahjoub Benmoussa) in hopes that he can suggest a solution to Karim’s “problem” (presumably some form of religious-based conversion therapy). When that doesn’t pan out, Fatima seeks to reason with Karim to reach a compromise, drawing upon her own experiences in which she was pushed into making sacrifices of her own (both romantic and professional) for the sake of preserving the peace in her family, decisions that she matter-of-factly chalks up to “that’s just how things are.” She hopes Karim will willingly follow suit, too, even if it means making life choices that don’t meet his needs.

In between arguments and these strained “negotiations,” Karim’s time in the closet provides him time to reflect on his circumstances, both in his recent past and in his youth, shown in flashbacks and dialogues with his younger self, as well as in memories of his early days with Kofi and in several surreal sequences. He especially ponders the turmoil experienced by his gay cousin, Soufian (Nasrdin Dchar), who endured torment at the hands of his family for being “different” even when he was younger (Rayan Berlhazi Alaoui) and who ended up trapped in an unhappy sham marriage just to please his relatives. The two were quite close, and Soufian often confided in his cousin, especially where orientation matters were concerned. Soufian desperately wanted to stop living a lie, though Karim repeatedly told him to stay silent to avoid undue disruption, a recommendation that he came to regret when tragedy struck.

Others express their regrets, too, especially Fatima. She laments some of the decisions she made about her own life, such as walking away from her relationship with a young man she adored but whom her parents disliked and “settling” for Abbas, a life partner who wasn’t her first choice but whom over time “she learned to love,” something she believes Karim is capable of, too. She even goes so far as to suggest that the family’s immigration to the Netherlands was a mistake, that perhaps things would have been better off for Karim if they had stayed in Morocco. But, as Karim observes, that wouldn’t have worked out either since his orientation would have been the same there as it has turned out to be in the family’s new homeland. What’s more, Karim tells his mother that she knows this, too, since he’s aware that she knew he was gay from the time he was a boy, even before he understood it (a common occurrence among gay men and their mothers), an acknowledgment she begrudgingly concedes.

As the arguments and discussions carry on, the situation grows increasingly tense, especially when it appears that no one is closer to any kind of a resolution after hours of heated, stressful back-and-forth. And, even after all that, much remains to be seen regarding how matters play out. Will Karim finally emerge from his closet, both literally and metaphorically? Will his relationship with Kofi survive? Can Karim’s family accept him for who he is, or will he continue to be subject to their unrelenting scorn? One hopes that matters will turn out well, though the road to reaching that point could readily become a rough and rocky path. And to think it all centers on simply receiving the recognition and just due that he believes he deserves just like anyone else, regardless of what his sexual orientation might be.

In essence, the persistence of increasingly outdated and outmoded notions such as these stems from the steadfast embrace of the beliefs that underlie them by their diehard proponents. That’s significant, too, given that our beliefs manifest the reality we experience thanks to the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains these intangible resources are responsible for generating that result. Some of us – and almost assuredly nearly all of those who hold on to these archaic ideas – may not have heard of this school of thought, which likely accounts for the endurance of these outlooks in certain segments of society, such as those depicted here.

Superficially speaking, these manifestations endure in part because of the specific beliefs directly supporting their materialization. But, as becomes apparent in the film, there are underlying beliefs supporting these notions. These thoughts and intents are arguably even more powerful, given that they provide backing and “justification” for the existence of these other beliefs that arise from them. These notions – often called “core beliefs” – act like the operating system of a computer on which all of the applications run. Because they function at a “foundational” level, they tend to be stronger in nature, with greater endurance capabilities, both of which make them more challenging to alter. And, consequently, they also tend to fuel the “applications” more intently, causing them to persist longer than other types of beliefs that are fundamentally easier to rewrite.

One need only look to many of the statements that Fatima and Abbas make in the film to understand this. For instance, consider their beliefs about what people would think if word about Karim’s gay orientation were to get out. But what is the real issue here? Is it because their son is leading an alternative, misunderstood lifestyle or because he’s simply doing something outside of widely accepted (and expected) conventional norms? And, as for the “shame” he’s allegedly bringing upon his family, isn’t that essentially attributable to the appearance that his family is tolerating (perhaps even sanctioning) something that goes against social and cultural conventions? (How dare they!) Consequently, the supposed disgrace associated with engaging in such “unacceptable” behavior is something that those seeking to fit in may find to be too high a price to pay for their actions; as they regrettably come to see things, such conduct must be squelched to avoid the inevitable shunning and scorn that would be sure to follow.

As much as Karim may dislike such conditions, he, too, has bought into it for a long time. He believes he must hide his sexuality at all costs to avoid the heartache it would cause him in relations with his family and their extended community. In fact, he abided by this thinking so thoroughly at one time that it provided the basis of the advice he gave his cousin. This thinking is even apparent in the unfolding of seemingly simple acts, such as Karim’s insistence that Kofi draw the curtains in his high-rise apartment building whenever he comes over for a visit, a demand made out of fear that someone on the outside may look in and see the two of them together. This could be seen as somewhat extreme, even paranoic, but it shows the lengths to which Karim is willing to go in order to safeguard his secret and to protect himself from those whom he believes would unduly ridicule him for it.

Karim’s actions in this regard reveal another deeply ingrained belief that may be hard to change yet carries significant consequences – his willingness to give away his personal power. To many of us, such a belief would be unthinkable. However, considering what he believes he could stand to lose, he sees it as an “acceptable” compromise. The problem with that, though, is that he runs the risk of potentially giving away so much just to assuage the views of others. Is that really worth it? Is abandoning one’s own happiness for the sake of appearances truly a beneficial trade-off? The limitations in that seem almost as confining as the size of the closet space he occupies, both physically and metaphorically.

Then there are also the beliefs based on the idea of “if we had to do it, then you should be willing to do it, too.” Consider the observations Fatima makes about giving up the romantic interest and career choices she wanted simply to please others, as well as her reconciliation to the idea “that’s just how things are.” This is another case of capitulation to the expectations of others and the relinquishing of one’s personal power. She believes those kinds of sacrifices are an accepted part of everyday life and that others – like Karim – should be just as willing to go along with them as she did. That may have been fine for her, but her son obviously can’t lay claim to the same notion. Indeed, why should he have to do it just because others rolled over and played dead? What kind of an expectation is that? And who decided that such acts were the “right” thing to do in the first place?

The presence of these core beliefs illustrates that the intentions behind our manifestation efforts can be more complicated than we might think. They carry the potential to drive many aspects of how we live our lives (and not always with the most desirable outcomes). Therefore, it behooves us to take a close look at exactly what beliefs underlie what we’re attempting to create for ourselves. Such an introspection could reveal some ugly little secrets that we don’t even recognize yet could be responsible for thwarting us in realizing what we hope to achieve. It’s important that we never lose sight of the fact that we each create our own reality, not the one that’s intended to satisfy the needs, wants and desires of others. They can do that for themselves, and we’d be best off letting them do just that – and not expect us to do it for them.

As this film so aptly illustrates, there comes a time for many of us when enough is enough. Such is the case with this film, based on the stage work of actor Fahd Larhzaoui and drawn from his own personal experiences. The ordeal the protagonist undergoes here may be a difficult one, but it also represents an opportunity to finally get things out in the open once and for all. The picture’s inventive storytelling approach, deftly punctuated with well-positioned comic relief, unearths an array of entrenched revelations that apply not only to the beleaguered son, but also to his other family members and his loving partner. Writer-director Shariff Nasr’s debut narrative feature makes an impressive, albeit controversial, statement about knowing when to hold on to, and when to let go of, tradition, culture and even ties to kindreds when toxic bonds to those connections no longer serve us. The sequence of events may come across as somewhat meandering at times, but, given the confusion and frustration in play here, who’s to say that one could remain completely rational when undergoing such as analysis, reflecting the conditions present in the mind of the protagonist at the time. Any deficiencies in this are skillfully concealed by the picture’s excellent cinematography and production design, as well as the superb performances of its fine ensemble cast. “El Houb” represents a noteworthy start for a filmmaker who obviously has much to offer, a career that I can’t wait to see develop and unfold. The picture initially played the film festival circuit but, thankfully, is now available for streaming on multiple online platforms.

If we truly hope to create a better world for ourselves, we have to begin with the concept of mutual respect, one whose underpinnings include recognition and acceptance, qualities that are, regrettably, still lacking in some quarters of this planet. Indeed, if we’re unable to afford one another something as basic and decent as this, we may be holding out false hope for circumstances ever meaningfully improving. However, if we’re able to open our minds just enough to allow these attributes in, we just might be able to turn things in the right direction. It would be to all of our benefit if we could bring enough love into this world to make it the kind of place it’s capable of being.

Copyright © 2022-2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment