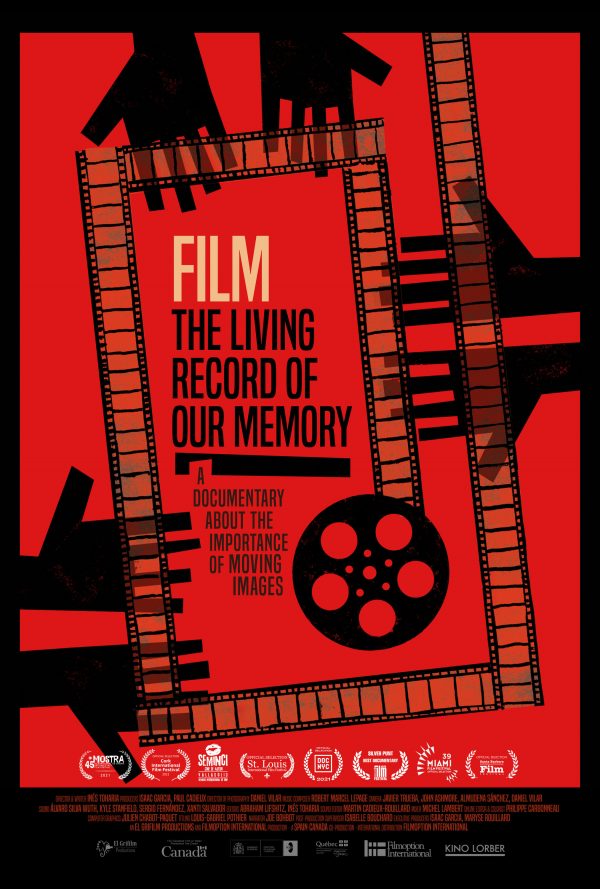

“Film, the Living Record of Our Memory” (2021 production, 2023 release). Cast: Interviews: Ken Loach, Costa-Gavras, Wim Wenders, Ridley Scott, Jonas Mekas, Patricio Guzmán, Margaret Bodde, Joseph Bohbat (narrator). Archive Footage: Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Sydney Pollack, George Romero, Ben Mankiewicz. Director: Inés Toharia Terán. Writer: Inés Toharia Terán. Web site. Trailer.

Imagine if there were no “Casablanca” (1942). No “Jaws” (1975). No “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), no “Avatar” (2009), no “Wizard of Oz” (1939). The prospect is unthinkable, even to the most casual moviegoer (imagine what that would mean for an avid cinephile). That’s what we’d face if no concerted effort were made to preserve these films for posterity. Surprisingly enough, however, this is a practice that, until recently, received far too little attention – and with devastating consequences. Fortunately, this subject has been garnering wider consideration, but it’s one about which we need to remain vigilant. That’s the message to come out of an impressive new documentary about this topic, “Film, the Living Record of Our Memory.”

Film has become so ubiquitous that we take it for granted. From big screen epics to intimate arthouse dramas to revealing documentaries to home movies, we see these cinematic records of us and our world virtually everywhere we look. It’s a phenomenon that’s present globally, too, one that spans all seven continents. And, because these images have been committed to what’s perceived to be a fixed medium, we tend to assume that these records will be with us permanently. But will they?

As writer-director Inés Toharia Terán’s compelling new documentary reveals, that’s not an assumption we should make – indeed, far from it. This excellent examination of film preservation efforts is an eye-opening revelation, showing us just how much of movie history has been lost – an estimated 80% of all silent films ever made and roughly 50% of those created since the invention of talkies. The documentary explores the reasons behind these tragedies, as well as the efforts that have been made to save and/or restore pictures that could have easily – or still might possibly – become lost without concerted initiatives to protect them.

Without being alarmist in tone, this film makes an impassioned case for the need for preservation. But that plea nonetheless raises the question of how and why these movies have become lost in the first place. And, as this documentary pointedly shows, there are a variety of reasons behind this.

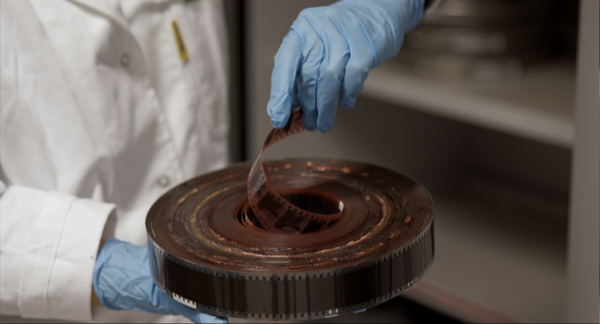

To understand this, it’s crucial to know something about how many early films were made and looked upon. In most instances, the images of these pictures were committed to something called nitrate film. It provided good image quality, but there a few important catches that came with it. For starters, nitrate film had a high silver content, and, given that, the minerals contained within it were considered more valuable than the finished works it captured. In large part, that’s because movies were seen as a novelty (and an easily disposable one at that), not as the legitimate art form they’re considered today. Many pioneering filmmakers and distributors believed that their movies had little residual value beyond the revenue they generated from their initial release. After all, they assumed, who would want to watch something they’ve already seen?

Because of that, many reels of nitrate film were recycled after the movies they contained had had their premiere runs at neighborhood nickelodeons. The silver in the film was retrieved and employed in what were considered better, more practical uses. The reclamation of this precious metal thus became a lucrative incentive for filmmakers and distributors strapped for cash.

To complicate matters, nitrate film was highly flammable. Screenings of pictures created with this technology were potentially dangerous to projectionists and, possibly, theater patrons and employees when the devices used to show them generated too much heat. This inherent pitfall led to the destruction of many films (especially during the silent era), sometimes even when simply in storage and not being run through projectors. Warehouse fires containing huge stockpiles of nitrate-based films proved devastating, both in terms of their financial and artistic losses.

When avid movie enthusiasts saw what was happening, they became concerned. But they had little initial success in generating interest in film preservation. To begin with, they had difficulty convincing potential backers for this effort that movies were a legitimate art form and not just some inconsequential passing distraction. At the same time, they also needed to convince studios and distributors that the archives they proposed to create for this purpose weren’t in competition with them. They needed to allay any fears that their intention was designed to siphon off revenue from those organizations. And, because of those roadblocks, progress at promoting preservation was slow for a very long time.

In addition to these issues, preservationists had to contend with other challenges. In many cases, the methods used for storing movies – both on nitrate film and on safer alternatives developed later – were often inadequate, leaving the materials subject to decay from ambient environmental conditions. Heat and humidity did in many offerings, especially among those stored in locations where these climatic conditions prevailed. Tropical locations often proved fatal to saving many pictures.

But deterioration was not the only culprit behind film loss. In some cases, censorship by authority figures led to the intentional destruction of movies considered subversive, as was the case in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, for example. In fact, many of the pictures that managed to survive those eras did so only because they were smuggled out of the country and placed in the hands of capable caretakers. Careless management in studio archives also led to the loss or destruction of many pictures whose curating was haphazard. Poor storage conditions and record-keeping led to considerable harm, issues that were often compounded when many smaller studios and distributors were sold or consolidated. And, of course, there were the aforementioned recycling programs that resulted in the willful destruction of films for their silver content.

Despite the establishment of a number of pioneering archive facilities in the US and Europe, preservation efforts made little progress until some of the movie industry’s most noteworthy productions began to be placed in jeopardy. That raised some significant red flags for industry leaders, particularly directors, who saw what the viewing public and future generations could lose if steps weren’t taken to curtail this decline. Leading the way in this effort was filmmaker Martin Scorsese, a diehard movie lover who couldn’t bear to see these works disappear. He led an aggressive campaign to promote this cause, backed by peers like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas and Sydney Pollack, along with directors from outside the US, as well as an array of technical experts and producers who wished to see their works (and their investments) preserved. This effort has since led to stepped-up efforts to further the cause before more works are irretrievably lost.

It should be noted that this is an initiative that’s not limited to the annals of Hollywood. It’s global in scope, including initiatives that have been launched in Latin America, the Caribbean, Europe, Africa and Asia. What’s more, it’s not restricted to theatrical releases. Preservation activists have also strongly encouraged the protection of personal projects, such as home movies – not by seeking to necessarily include them in formal archives but by educating amateur camera operators to consider employing some of the same protective techniques for their materials as those used to save big screen classics. These films may not be important to everyone, but they’re certainly cherished items to those who made them for themselves and their families.

This film examines some of the efforts and technology used to save these films, both from a preservation standpoint and from a restoration perspective. In many cases, these restorative programs have made it possible for contemporary viewers to see how these pictures were originally intended to be shown but were hampered by technical limitations that have since been overcome, efforts profiled through several specific cinematic case studies. Such efforts have not only kept these movies alive, but they have actually brought them to life in ways that were once thought unimaginable – and that would almost assuredly delight those who first created them.

As noted above, there are those who have erroneously assumed that commitment of images to a fixed medium guarantees their permanence, a notion that carries potentially dangerous consequences for uninformed movie lovers. And, as the film also astutely observes, this is a caution that needs to be borne in mind even when it comes to the use of more contemporary (and supposedly superior) image storage technologies. Digital preservation, for example, may offer an opportunity to forestall the inevitable decay of conventional celluloid, but are the effects ever-lasting? There’s no airtight guarantee that these new technologies ensure permanence any more than film itself. In light of that, director Terán and her interview subjects make clear that preservation is an ongoing effort, one about which we need to be vigilant if we hope to preserve these materials, lest we fall prey to the same kind of apathy and disinterest that allowed so many movies to become lost in the first place. If we truly wish to maintain these films, we have to remain diligent to see that the intent behind this effort carries through to fulfill its goal.

There are a number of good reasons for this, but one of the most basic is that making movies is a demonstrative act of creation, one whose fulfillment is the end result of a dream, a belief that these conceptual works of art can truly materialize in physical form. Such are the outcomes of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest our reality and everything within it through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents. That notion is present in the nature of film itself – when those flickering individual images are played in sequence and exposed to a light source as they’re projected onto some kind of screen, they magically tell stories, bringing ideas that were once inherently intangible into tangible existence. Not all such stories are equally compelling to everyone, but they all have their origins in the consciousness of their creators, and their fully fledged realization means something to those who brought them into being, even if they mean little or nothing to anyone else. In short, they’re each bona fide acts of creation and deserve to be respected and preserved as valid artistic materializations.

But there’s more to it than that (even if the foregoing consideration is sufficient enough in itself). For starters, movies are rarely the creations of a single individual; they’re intricate collaborations, frequently involving many participants from the directors to the producers to the performers to all of the technical and support staff who work on the finished products. In that regard, they are truly acts of co-creation, all driven by the thoughts, beliefs and intents of those who contributed their input into these manifestations. And everyone who participates in these endeavors deserves to have his or her contributions respected and preserved, no matter what others may think about the end results.

Then there’s the nature of the content and the value it contains. This is particularly important where films of a documentary nature are concerned. Consider what might have been lost if the preserved footage of a number of historic events had been allowed to disappear. What record would there have been of the first moon walk? Likewise, what would we have known about man’s first recorded visit to Antarctica, such as the explorers’ whimsical reaction to their first awareness of the existence of penguins? Then there are events whose recordings poignantly remind us of how to keep history from repeating itself, as seen in documentary footage of the persecution of Jews in pre-World War II Europe. Even the sentimental value of family events in home movies could be lost if these materials are allowed to disintegrate; film of mom and dad’s silver wedding anniversary may not carry much weight in the history of humanity, but it certainly would mean a lot to their descendants if the footage were to vanish. Beliefs associated with the need to protect the images of events big and small should be enough in themselves to promote their preservation.

And that brings us to a significant reason for the foregoing – the emotional impact that films carry, especially when it comes to forging meaningful connections between the art and those interacting with it. As famed director Ingmar Bergman observed in a 1991 edition of Sight & Sound, “No art passes our conscience in the way film does, [going] directly to our feelings, deep down into the dark rooms of our souls.” That statement alone is perhaps one of the most insightful assessments of what movies can do for us individually and collectively, a profound capability that surpasses virtually any other art form. Indeed, when one embraces that belief and witnesses its impact in action, there’s arguably no viable contention that can otherwise counter it.

When movies are looked upon in that sense, their impact can be substantial. They serve as valuable teachers. They inspire us to conceive new ideas and explore previously uncharted territory. And they serve as a mirror of our world, showing what’s right with it and what could use improvement. But none of that might be possible if these visual records were not suitably protected and preserved.

Drawing attention to the meaningful effects that movies can have on us has been my mission for more than 15 years, as demonstrated through my three books and countless website blogs. I passionately believe in their value to inspire us in helping to write the scripts of our lives. And that’s why I also so fervently support efforts aimed at film preservation.

The loss of so many films over the years demonstrates just how delicate and precious an art form movies are. What we see as a powerful and impressive creation today could easily become a crumbling pile of rubble in short order if we don’t take steps to ensure its viability and continued existence. Thankfully, there are a growing number of curators out there who zealously believe in the value of preserving these works and the ability to come up with the means to make this possible. We all owe them a debt of gratitude for their efforts and what they’re enabling for us and for those who succeed us.

Film preservation is such a huge, multifaceted subject that it may be difficult to get one’s hands around it. However, writer-director Inés Toharia Terán has done just that in this compelling new documentary. It effectively covers a tremendous amount of ground without becoming scattered, presenting its material in a highly intelligent, well-organized manner. Terán’s work is particularly impressive from the standpoint of comprehensiveness, showing the impact that this effort has had on film collections from around the world, from all ages past and from all genres, not an easy feat given the breadth of content involved. Through interviews with leading directors, archivists, restoration professionals and photographic industry experts, viewers gain an insightful new appreciation for why these celluloid records matter to us and why it’s important to make the effort to save them from neglect before they’re gone forever. Admittedly, some may find this offering a little overlong, but, in my view, better more than less when it comes to a showcase aimed at purposely illustrating the need to preserve these precious and otherwise-irretrievable materials. And, to its credit, the film does a fine job of keeping its narrative from becoming too technical, a noteworthy accomplishment for a subject that could easily become overly burdened by indecipherable jargon. This work is must-see viewing for anyone who loves movies and passionately desires to see as many of them curated as possible, making their continued existence available to posterity as a genuine living record of our memory. The film is available for streaming online.

To ardent cinephiles, losing a movie forever is almost akin to the death of a loved one. The loss is felt personally, but, given the intimate connection this art form often forges between subject and viewer, that’s entirely understandable. We’ve made great strides in furthering this cause, but there’s always room for improvement, a vital consideration in the face of a ticking clock. This should thus serve as a powerful reminder to take action before it’s too late. But, as long as we believe in such a possibility, there’s no reason we can’t make that happen. The magic of the movies proves that virtually anything conceivable is indeed attainable. So let’s get busy and do that while we still have the chance.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment