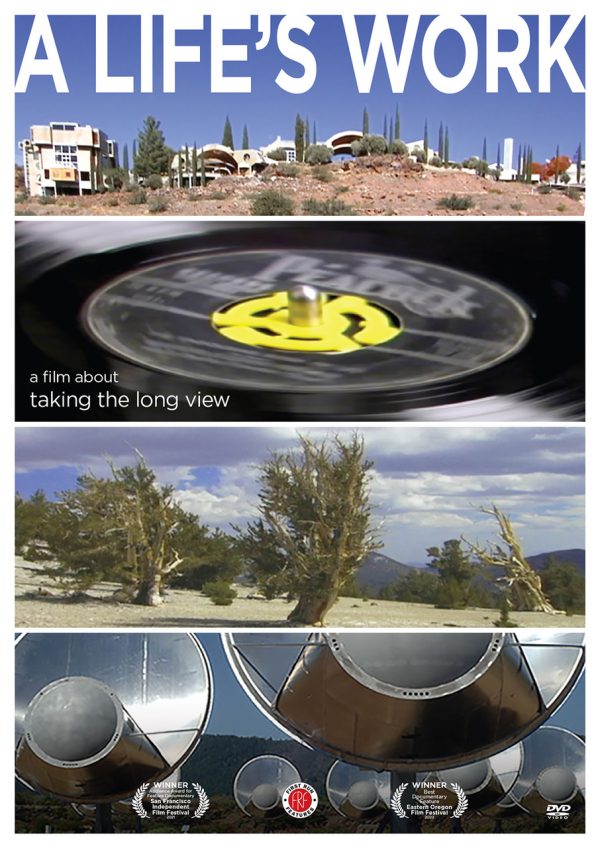

“A Life’s Work” (2020 production, 2023 release). Cast: Jill Tarter, Robert Darden, David Milarch, Jared Milarch, Paolo Soleri, Jeff Stein. Archive Footage: Frank Lloyd Wright. Director: David Licata. Web site. Trailer.

Many of us have trouble seeing into the future, sometimes no more than just a week or so in advance. That lack inherently leaves us wondering what’s next and how to plan for it. As a result, we often tend to go from moment to moment, unaware of what awaits us around the corner until we actually find ourselves in the midst of it. But not everyone operates that way; some of us have the foresight to imagine our world far down the road with elements that reflect our vision for what could lie ahead. This is particularly true when it comes to what we want to accomplish in our lives. The goals in these instances can be quite ambitious, too, frequently involving undertakings that will take a long time to fulfill, sometimes even extending beyond the lengths of our lifetimes. And it’s ventures like these that provide the focus for the inspiring new documentary, “A Life’s Work.”

What do searching for evidence of extraterrestrial life, an African-American gospel music preservation program, a revolutionary architecture project and an organized effort to clone legacy trees have in common? They’re the undertakings profiled in director David Licata’s impressive, uplifting new film. All four of them were launched and managed by individuals who were willing to take a long-term view toward their execution and fulfillment, perhaps for a duration that would likely exceed their own natural lives. They represent projects that many of us would probably look on as unduly daunting and perhaps even hopelessly impractical, especially given that we might never be able to see them completed. However, considering the importance that these innovators attached to these endeavors, they couldn’t bring themselves to step away from them, even if there was a chance that they’d never see them reach their hoped-for conclusions.

Such dedicated efforts thus genuinely represent the chosen life’s work of the visionaries who initiated them. It should go without saying that the commitment required for these undertakings was undeniably substantial, often involving many considerations that went beyond the immediate needs of achieving the desired outcomes. Documenting these endeavors also required a comparable commitment from the filmmaker, who spent 15 years recording the work that went into these enterprises. But, when one considers that the life’s work of these individuals is involved, it should come as no surprise that it would take such a protracted time to bring the record of their efforts into being. And, even with that kind of commitment, it’s not outside the realm of believability to say that the cinematic recounting of these stories itself remains fundamentally incomplete, even after all that time.

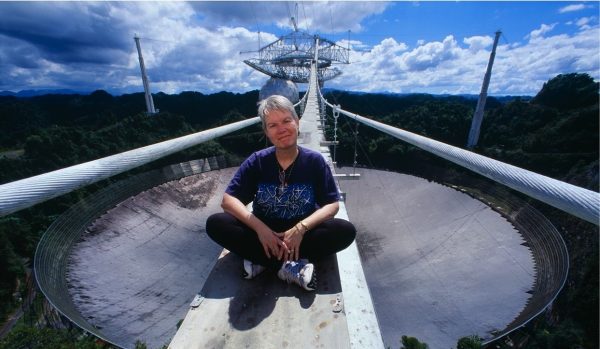

The range of ventures examined in the film is quite diverse, not to mention truly impressive in scope. For starters there’s the work of Jill Tarter, longtime (and now-former) head of SETI, the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence project. This former government-funded program (now supported by private financing) searches the heavens for evidence of life beyond our planet by recording and interpreting radio telescope signals, all in hopes that they might provide clues about what – or who – may be out there. Admittedly, this could represent a long shot attempt at making contact, but, as Tarter maintains, is that any reason not to look? Should this effort pay off, it could open the door to one of the greatest scientific discoveries of all time. That seems to be a worthwhile outcome, no matter how heavily the deck may seem to be stacked against us.

Closer to home but no less important, there’s the effort of Robert Darden to save a portion of our artistic heritage that’s in danger of being lost forever. As the founder of the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project, Darden has earnestly sought to preserve the rapidly disappearing recordings of African-American gospel musicians from years past. According to Darden, an estimated 75% of these recordings has already vanished, never to be recovered. Because of this, he has made it his mission to scour private collections, vinyl record store inventories and other sources to find these works before they’re gone and to secure their transfer to electronic versions so that they may be preserved for posterity.

Preservation is also the theme behind the work of David Milarch and his son, Jared, who, through the Champion Tree Project, have worked tirelessly to collect the DNA of endangered legacy species, such as the American elm and the California redwood, so that it can be replicated to produce viable new saplings. Their hope is to restore the populations of these vanishing species so that future generations may enjoy them. And, given the ecological and potential medicinal applications of these trees, the Milarchs also hope that the preservation of these species can benefit mankind in ways that extend beyond their sheer horticultural beauty.

Just as the Milarchs’ legacy tree preservation efforts are aimed at benefitting our future well-being, so, too, does the ongoing work of architect Paolo Soleri, who spent years constructing his innovative designs prior to his death in 2013. Soleri, a onetime protégé of iconic architect Frank Lloyd Wright, is credited with founding the “arcology” movement, a discipline aimed at fusing the principles of architecture and ecology. Given what he saw as the squandering of resources and land associated with suburban sprawl, Soleri focused his efforts at creating ecologically friendly architectural designs characterized more by “building up” rather than “building out.” He subsequently created a number of designed communities to reflect these notions. Over the past five decades, Soleri and his followers have worked on constructing the first of these communities, the experimental town of Arcosanti, AZ, about 70 miles north of Phoenix. Progress has been slow but steady over the years, with Soleri’s work taken over by protégés like Jeff Stein and his colleagues in the time since the creator’s passing. It’s hard to say whether the work on this community will ever be finished, but, as Stein observes in the film, when is any community ever truly finished? It’s a work in progress, one that reflects the life’s work of not only its originator, but also of those who share his vision and seek to carry on with it.

That last statement essentially embodies the mindset of those who initiated and have continued projects like these and others. Those charged with carrying out these efforts unquestionably see them as their life’s work, and they make no apologies for it, regardless of how critically others might view them. Were it not for individuals like this, however, we might not have realized many of the accomplishments that have been achieved in many fields of endeavor. Perseverance, it would seem, does win in the long run.

Considering the immense scope behind these projects, one might legitimately wonder why anyone would be willing to take them on. But, in these cases (and virtually any others like them), the answer is likely to be the same in each instance – because those embracing them believe that they can be accomplished. It doesn’t matter to them how long it would take, even if they don’t live long enough to see their completion. They believe in the value and viability of these ventures, no matter what, even if some might see them as pursuing Quixotic causes. Rather, these dedicated innovators simply look upon their work as big tasks that need to be tackled for the betterment of humanity.

The beliefs driving these pursuits are quite potent, to be sure. But, as anyone who incisively understands the nature of beliefs knows, they’re powerful and persistent resources. And, when backed by sufficient resolve and faith, they’re tremendous tools that can enable us to accomplish almost anything. Such are the end products of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we can employ these resources to create the reality we experience, including all of the elements within it. This is not to suggest that such materializations can spontaneously manifest into existence with the snap of one’s fingers, but they can plant the seeds that lead to the sprouting of what they’re ultimately intended to create. The driving forces behind the projects examined in this film may not have heard of this school of thought, but it’s obvious they have conviction behind their beliefs and have mastered the principles that make this philosophy work.

Regardless of how quickly or thoroughly these creations manifest, those seeking to bring them into being nevertheless are convinced they’re achievable. That’s apparent by how long they have allowed themselves to remain committed to their fulfillment. Paolo Soleri, for example, believed in the veracity of the Arcosanti community and continued to work on its development even when faced with severe funding issues. To keep his dream alive, he developed workarounds, such as recruiting volunteer crews to construct the buildings that eventually materialized, despite the obstacles that slowed their progress. He also devised a unique way to raise money by crafting wind bells that were sold in galleries and gift shops to generate much-needed cash. These measures may not have been solutions that immediately sprang to mind to keep the project going, but they worked nonetheless, and belief in their viability ultimately proved correct.

That kind of thinking has also been driving the SETI project, even though it has yet to produce the definitive proof of its core mission. According to Jill Tarter, the program has experienced issues not unlike what Soleri confronted with the Arcosanti project, namely, maintaining a steady flow of funding. To that end, Tarter has said that one of her chief roles in SETI was to serve as its “head cheerleader,” enthusiastically drawing attention to the cause, the value of its purpose and the need to raise money to keep it going. In many ways, her efforts echoed those of Dr. Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster) in the 1997 sci-fi offering “Contact” in which a plucky astronomer passionately endeavors to keep her extraterrestrial search program alive at a time when many others were convinced it was foolhardy nonsense, an outcome disproved by the results it ultimately achieved. One could say that Tarter forged ahead with that same kind of optimism and commitment when she headed the real-world version of that program. And her belief in it just may prove correct someday as well.

While the Arcosanti and SETI programs are seeking to chart new ground, the Black Gospel Music Restoration Project and the Champion Tree Project are aimed at preserving creations that are in danger of becoming lost. Because of what could occur to these commodities without adequate attention, the value of preservation-based programs like these is just as great as that behind the aforementioned groundbreaking endeavors. However, even though these projects are not exploring new territory, that’s not to say that the effort required to fulfill them is any less great, which means that the power of the beliefs driving them must also be just as significant.

Robert Darden and David and Jared Milarch understand this, and they employ this thinking in their respective undertakings. They also have a realistic sense about what may or may not be attainable. through their efforts Darden, for example, understands that not every legacy recording can be saved, as evidenced by the loss of 75% of such works that has already occurred. Likewise, the Milarchs appreciate the fact that a number of the legacy trees they pursue no longer possess viable DNA that can be used for cloning, despite the continued existence of specimens of these species. But, then, Darden and the Milarchs don’t let these potential shortcomings deter them in their efforts. As Darden observes in one of his interview segments, the gospel music restoration project may not be able to save everything, but he can take satisfaction from every one of the recordings that it is able to preserve. That’s an accomplishment in itself, even if it doesn’t represent the totality of what had been created at one time. It’s a principle that anyone seeking to preserve any kind of commodity from becoming lost can take pride in, regardless of what’s at stake.

No matter how much progress is made on projects like these, the fact that they continue, with beliefs underlying and supporting such perseverance, deserves meritorious recognition, particularly for the dedication of those carrying them out. These efforts, in fact, serve to validate the very essence of the power and persistence of our beliefs, and this film celebrates that notion. Let’s hope we never lose sight of that, no matter what projects we may choose to undertake.

How inspiring it is to see committed individuals embark on Herculean tasks like these, even if just for the sheer passion they engender and what they can ultimately contribute to the well-being of mankind. Filmmaker David Licata, who spent 15 years following four such ventures, provides an insightful look at these projects and the implications behind their execution. In telling these stories and assessing the efforts of their progenitors, the director examines not only the particulars behind these endeavors, but also the motivations and commitments driving their creators, as well as the challenges associated with carrying out these undertakings. The film presents a balanced view of each of these projects, told economically and on point, without extraneous padding or irrelevant material, a refreshingly welcome relief considering how many less-than-satisfying recent documentaries have been put together. What’s most significant about this offering, though, is the inspiration that it prompts among viewers. Audience members are treated to a variety of illustrations that truly depict what constitutes “a life’s work” in every sense of the expression. It’s quite uplifting to see what our visions and beliefs can yield, and this film brings that notion front and center for all to see.

Taking the long-term view toward a project can indeed be overwhelming, especially since there’s no definitive guarantee of seeing any reward coming from it. But is that the only reason behind tackling such pursuits? If we were to adopt such a view, it’s likely that much of what mankind has accomplished may have never been realized. Rewards are truly satisfying outcomes to emerge from such efforts, but they shouldn’t be viewed as the starting point for taking on such challenges. If a venture has true value, the rewards will likely result anyway. It’s the work itself that matters, and, when it’s backed by the power of the right mix of beliefs, tremendous outcomes are possible. And that should be the most rewarding aspect to come out of all this.

Copyright © 2023, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment