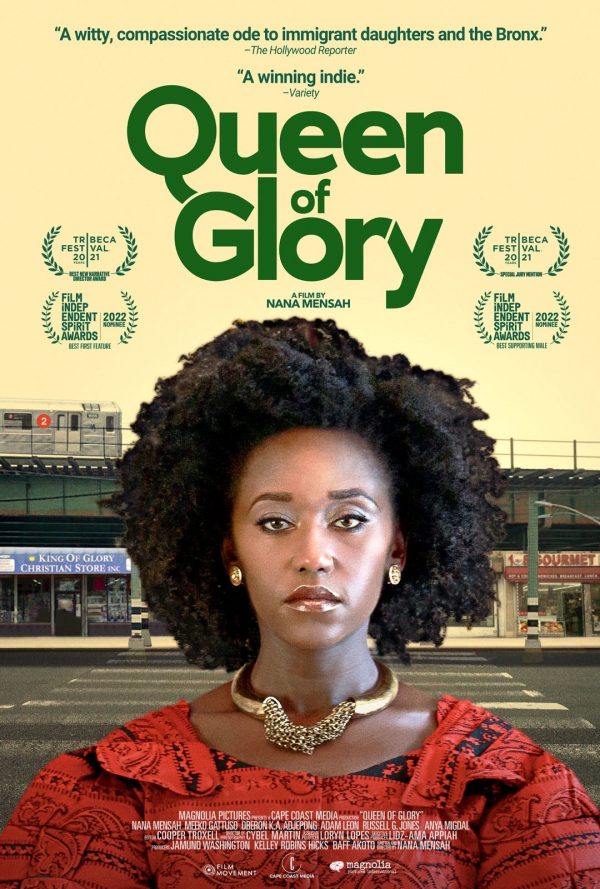

“Queen of Glory” (2021 production, 2022 release). Cast: Nana Mensah, Meeko Gattuso, Oberon K.A. Adjepong, Adam Leon, Russell G. Jones, Tanya Migdal, Anya Migdal, Alice Lebedev-Migdal, Ian Lassiter, Christie Mensah, Jennifer Mensah, Emma Kaye. Director: Nana Mensah. Screenplay: Nana Mensah. Web site. Trailer.

Life’s rough patches can be agonizing, frustrating and difficult, challenges that seemingly take us far afield from where we want to be. We often can’t help but wonder what’s behind such detours, especially when they appear to blatantly run counter to our hopes, wishes and dreams. What good purpose could they possibly serve? But, when we take the time and effort to explore them, we may find some hidden nuggets of wisdom and insight buried deeply within them. Such is the lot of a self-determined young woman struggling to sort out her life in a time of transition in the delightfully wacky new dark comedy-drama, “Queen of Glory.”

Sarah Obeng (Nana Mensah) is trying to outrun her past. As the US-born daughter of immigrants from Ghana, she’s spent her life trying to tactfully escape her background and become a modern American woman. She doesn’t openly disrespect her heritage, but she’s looking for something different for herself than what most of her family members want for themselves – or her. Still, despite her independent streak, Sarah is nevertheless routinely subjected to the loving but firm nudges of her relatives to steer her in the traditional direction that they genuinely believe is the only right course – and that she shouldn’t even be questioning.

In many regards, Sarah’s story is typical of what first generation American-born children of immigrant parents experience as they seek to find their way in life. Having grown up in the Pelham Parkway section of the Bronx, a predominantly middle class, blue collar neighborhood that serves as home to an array of immigrants of African, Latin and eastern European ancestry, she’s purposely distanced herself from her cultural background. This shift is apparent in her work, values and lifestyle. For example, she’s largely abandoned the fundamentalist African Christian religious beliefs of her upbringing in favor of a more contemporary perspective, a change that has prompted her to shed more conventional notions that she’s come to see as quaint, outmoded and out of step. That decidedly different approach to life is reflected in many regards, even her choice of career, having chosen to follow a science-oriented path as a neuro-oncology doctoral candidate at Columbia University.

But the differences don’t end there. In addition to moving out of her childhood neighborhood, Sarah’s quietly been dating one of her grad student colleagues, Lyle Cummins (Adam Leon). As a married Caucasian man, he’s probably not what her family would expect – or approve of – as marriage material for Sarah, but she’s committed to pursuing the relationship, especially when he assures her that he’s planning to divorce his wife and resettle in Ohio. Availing herself of that added distance has considerable appeal for Sarah, as it will physically remove her even further from her past and give her the freedom to become the individual she wants to be.

As events progress, it seems Sarah is moving ever closer to fulfilling her dream. But that all changes when her mother, Grace, unexpectedly passes away. Sarah is suddenly thrust into a new set of responsibilities. She needs to make funeral arrangements and settle her mother’s estate, which includes selling her home and figuring out what to do with her mom’s business, a Christian bookstore called King of Glory.

Even though these developments take Sarah back into her old neighborhood and culture, she feels out of place. She’s been removed from these circumstances for so long that they seem strange to her. What’s more, she’s suddenly being required to handle tasks she’s never done before – planning a funeral, selling a house, and operating a business whose merchandise and marketing are totally foreign to her and her sensibilities. And, on top of all that, her plans for the future have been seriously derailed, leaving her up in the air.

Under circumstances like this, one might think Sarah’s story would be utterly bleak and devastating. However, given that she now finds herself ensconced in a proverbial fish-out-of-water scenario, she’s beset by an array of outlandish – and genuinely funny – situations. Her attempts at coping might not make her laugh, but they’re guaranteed to do so for viewers, especially as matters become further complicated by additional new developments.

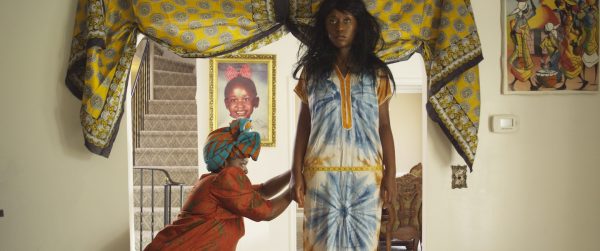

Sarah’s plans for tackling these tasks reflect what she sees as her rational contemporary sensibilities, actions that she assumes others should naturally agree with. For instance, when it comes to funeral arrangements, Sarah looks to arrange a simple wake in her mother’s home, one that resembles a subdued cocktail party more than anything of a funerary nature. However, her family members and mother’s friends see this as insufficient and insist on a more customary Ghanaian ceremony, an event characterized by elaborate rituals, extravagant “costuming,” and a massive spread of food, including many traditionally prepared dishes. It’s all new – and somewhat eye-opening – for Sarah, especially when she goes “grocery shopping” at a livestock market to buy “ingredients” that bring new meaning to the term “fresh.”

Then there’s the matter of selling Grace’s house, which Sarah goes about matter-of-factly, hoping that she can expedite the process to keep it from interfering with her moving plans to the Midwest. But that goes awry when her estranged father, Godwin (Oberon K.A. Adjepong), returns to New York from Ghana after a long absence. He sees the property as something that belongs in the family, even though his wife is no longer living there and the fact that he hasn’t done so in years. And, when Sarah protests, Godwin doesn’t hesitate to call upon his strong-arm patriarchal attitude to make his feelings indisputably known. Sarah sees this as yet another frustrating delay to keep her from moving on with her plans, not to mention the fact that it does nothing to smooth over relations with dad at a time when some parental support could probably do a world of good for her.

But perhaps the biggest challenge Sarah faces is deciding what to do about the business. She has no interest in holding on to it, given that it holds no appeal for her. She sees its merchandise and mission as simplistic and corny, clearly running afoul of her secular worldview. But what is she to do with it? She also must deal with her mother’s right-hand man, Pitt (Meeko Gattuso), an ex-con festooned in a plethora of tattoos who dabbles in making pastries laced with special ingredients and drops less-than-subtle hints that he’d like to take over the business. Sarah is somewhat puzzled by his interest in the bookstore, sensing that he doesn’t seem like the type to run an operation like this. But he recognizes the role it – and he – plays in fulfilling the needs of the neighborhood, whether it’s for religious greeting cards or specialty baked goods.

As all of these challenges unfold, Sarah tries to remain focused on her future with Lyle. But, as delays continually arise, she starts to receive mixed signals from him, both about relocating and following through on his divorce. It seems as though everything is collapsing around her, leaving her torn about the direction in which her life is headed.

Will Sarah be able to create the life she wants, or will she be unwittingly drawn back into circumstances that she quietly loathes? Can she evolve into a modern American woman, or will she be permanently saddled with the expectations of her immigrant family culture? And, if it ends up being the latter, does that represent an exercise in backsliding, or will it turn out to be something that’s not so bad after all? Moreover, isn’t there room for compromise, a hybrid solution that combines the best of both worlds? Is it indeed possible for Sarah to have her cake and eat it, too?

This is where Sarah needs to assess her beliefs about what she wants for herself. Perhaps she’s convinced herself that she’s pursuing goals that she thinks she wants but that, in reality, don’t fully align with the sentiments of her true self, what genuinely resides in the recesses of her heart. If she conducts such an examination, she might be surprised at what she finds, particularly in the area of her beliefs, the foundation of what gives rise to her existence. Such is the nature of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains these intangible resources manifest the world we experience – and that all begins with us.

It’s unclear whether Sarah has ever heard of this school of thought, but, if she truly wants to create the reality of her dreams, she needs to take the steps associated with it to realize that goal. And it may not be particularly easy, given that she’s obviously struggling to sort out everything she’s experiencing, including both what she expects to happen and what she doesn’t. Nevertheless, if our beliefs shape our existence, they’re behind both sets of manifestations. Some may find that hard to fathom, but, if beliefs underlie everything that emerges in our lives, that would include both what’s anticipated and what’s not. The trick is in figuring out why – and what we can do with tweaking our beliefs to bring us more of what we desire and less of what we don’t. The outcomes will reveal to us what beliefs we’re really holding on to, including both those that serve us and those that don’t. And, based on how things are transpiring in Sarah’s life, it’s obvious she’s got her work cut out for her.

There are several steps Sarah can take to make this process go more smoothly. For example, she could make a conscious effort to look for “clues” that would help guide her in her assessment. Such clues most readily take the form of synchronicities, those perfectly tailored “coincidences” that provide hints about where we are, what we’re doing and where we’re supposed to go. They’re so attuned to our circumstances, in fact, that they’re often accompanied by those “aha!” moments we find so uncanny. And, given their impact and personalized meaning, they’re not to be ignored. Of course, the reason for that is they’re essentially coming from us, fitting reminders and attention grabbers that arise as tangible manifestations of our own beliefs. Anyone who experiences such incidents and recognizes the highly personal nature of them should embrace them and try to understand them, not look on in mere blind wonder or seek to write them off as pure chance. Indeed, there is no “coincidence” in these “coincidences.”

Then there’s the effort to cut through the camouflage that may be obscuring our view of our circumstances. These outward façades hide the real truths we’re supposed to see, often leading us to the wrong conclusions and sending us down the wrong paths if we accept them without question and don’t recognize them for what they truly are. These manifestations are ultimately designed to help us sharpen our powers of discernment, to see the truth more clearly, frequently as a means to get a better handle on our own beliefs, as well as what we’re creating with them and why. Sarah could benefit tremendously from engaging in such an effort, especially since she’s being bombarded by so much of this as she seeks to sort out her life during this transition.

The foregoing practices are not only valuable in and of themselves, but they’re also important to something even bigger – the process of getting real with ourselves. If we’re truly to find happiness and contentment in our existence, we have to be honest with ourselves, examining, assessing and accepting our circumstances with personal integrity. To do otherwise could lead to serious bouts of self-deception that might take us a long time to overcome. To succeed at this, we must be willing to take a frank, unfettered look at things and use that as the basis for moving forward. This could involve such practices as being willing to accept hard truths. It also would likely help if we could learn to laugh at ourselves and our foibles, something for which Sarah has plenty of opportunities available to her in this story.

We should also be willing to accept the help that is available to us; we need not endure such scenarios by ourselves. And, fortunately for Sarah, there are a number of sources of assistance at her disposal. Most notably there’s Pitt, who genuinely seems to want to help her, even if his no-nonsense style sometimes comes across as a little brusque. Then there are Sarah’s neighbors, the Malinova-Thayer family, who often are willing to step in and help, even though they have more than their own share of comic challenges to resolve, many of which Sarah is able to assist them with. Indeed, one hand really does wash another.

Through these endeavors, Sarah comes to learn a great deal about herself, her life, what she wants and what she thought she wanted. She discovers how we don’t need to run away from our past to still be ourselves. Striking a balance between heritage and our hopes for the future need not be a mutually exclusionary process. Arriving at a happy medium can have a considerable impact in shaping our overall outlook, perspective and beliefs on life, making it possible for us to unearth the personal queen of glory that resides within each of us.

To paraphrase an old adage, you can take someone out of their native culture, but you can’t take the native culture out of that person. So it is here as Sarah as she struggles to assert her Americanized ways and distance herself from what she sees as her folksy, homespun roots and the discomforting uber-Christian, uber-chauvinistic values of her family members. But Sarah’s past is a big part of who she is, even as a self-determining adult, and reconciling it with her present and future is something many of us – but especially children of immigrants – must do. These are themes effectively brought to life in actor-writer-director Nana Mensah’s delightfully wry comedy, a delightful wacky exercise that effectively tickles the ribs of those of us who come from overbearing families. The deliciously wicked laughs served up here are reminiscent of those found in films like “Shiva Baby” (2020), “Home for the Holidays” (1995) and “The Forty-Year-Old Version” (2020). A few sequences feel a little drawn out, which is somewhat surprising given the picture’s comparatively short 78-minute runtime, but this is a film with its heart – and funny bone – in the right place, making for an agreeably amusing watch.

“Queen of Glory” has had what could probably be considered one of the longest roll-outs in movie history. Shot in 2014, the picture first started appearing at film festivals in 2021 and has been running at those events ever since. It recently earned a shot at a brief, limited theatrical run and, in all likelihood, should be available for streaming in the near future, but it’s an offering not to be missed. And, for its accomplishments, the film received two 2021 Independent Spirit Award nominations for best first feature and for Gattuso’s supporting actor performance, offering more evidence of this offering’s cinematic viability.

The frustrations we experience in life can be quite annoying, making us legitimately wonder why we’re enduring them. But maybe their presence is intentional, distractions designed to steer us away from life paths that might ultimately prove detrimental. It may take us some time to realize this, too, which could easily prolong the difficulties we undergo. However, if we look at them with a critical eye, we might just see that they occur to spare us greater grief down the road. And, considering that those “beneficial hindrances” ultimately arise from within us, we might come to see that these seemingly wayward developments are actually our own efforts to save ourselves. There’s much to be said for such forms of self-protection, proving that the greatest love coming our way truly comes from within us, and we should be ever thankful for that.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment