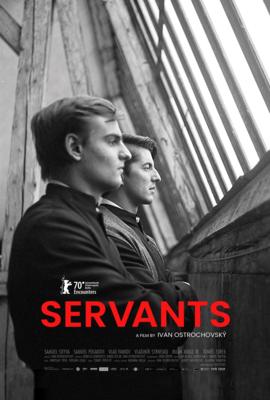

“Servants” (“Sluzobnici”) (2020 production, 2022 release). Cast: Samuel Skyva, Samuel Polakovic, Milan Mikulčík, Vladimír Strnisko, Vladimír Obsil, Vlad Ivanov. Director: Ivan Ostrochovský. Screenplay: Rebecca Lenkiewicz, Marek Lescák and Ivan Ostrochovský. Web site. Trailer.

In a world where it’s become all too easy to make compromises for the sake of personal considerations to the detriment of people, practices and principles, it’s become almost unfathomable that there are still individuals out there who are ready and willing to stick to their guns. Their intentions, methods and actions may not always be obvious, but the underlying beliefs and motivations are nevertheless solidly and undeniably in place. Implementing initiatives based on those values might not always be easy, especially when under extreme pressure from those who have conflicting agendas and who wield the power to prevent those efforts from bearing fruit, but it doesn’t stop those committed souls from trying. Such are the dynamics in place in what is supposed to be a sacrosanct environment that’s being threatened by the dictates of a repressive authoritarian state in the new historical drama, “Servants” (“Sluzobnici”).

Life behind the Iron Curtain in 1980 was a stunningly bleak existence. Finding ways to be at peace, let alone happy and fulfilled, under the authoritarian governments of the day was indeed challenging – and often dangerous, what with the constant scrutiny citizens were subjected to by menacing secret police organizations. Even ostensibly innocent activities, like the ability to practice one’s own religion, were under perpetual threat. That was especially true for those at the top of these institutions, those who spread the word of their faith to their flocks of eager followers. Their very ability to carry out this mission was itself challenging enough in light of the dim view the state held about religion generally. And anyone who preached spiritual concepts perceived as flying in the face of secular state dogma were censured or removed from their posts, of not worse.

Such are the strict circumstances under which a Roman Catholic seminary operates in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. In the wake of the country’s political uprising of 1968, when attempted liberalization efforts were flaunted in the face of Soviet overseers who later brutally squelched the initiative, authorities have severely cracked down on any alleged seditious activities or the spread of subversive ideas, a policy applied across the board in Czechoslovakian society, even in the churches. In fact, the seminary’s ability to stay open and functioning has even been looked upon by the institution’s leadership as a tremendous privilege, one that high-ranking staff members have diligently sought to protect, even if that sometimes means making deals with the devil.

But can the power of ideas truly be contained? It’s an ongoing struggle for officialdom, one that continually forces government authorities to employ drastic measures to keep under wraps. However, it’s even more of a challenge in a place like the seminary, where thoughts, beliefs and principles are the essence of what its teachers and students deal in – and that are difficult to suppress through what they share with one another and their congregations. Indeed, how can the empowering message of Christ be diluted to avoid being in opposition of the dictates of the state and still ring true? In fact, wasn’t that at the core of what Jesus sought to convey through His teachings? How can His present-day disciples be expected to do any different and remain true to their callings and those notions?

That’s the challenge now being put to the leadership of the seminary. The head of the facility, Dean Tiber (Vladimír Strnisko), walks a tightrope as he seeks to be true to the faith while keeping authorities from shuttering the institution. He frequently meets with Dr. Ivan (Vlad Ivanov), a ruthless secret police interrogator who scrupulously investigates any suspicious activity and never hesitates to employ whatever tactics are needed to obtain information, seek atonement from transgressors or silence those unwilling to comply with government policies. It’s troubling for the head cleric, but he begrudgingly does what he has to do keep the seminary open.

Try as he might, however, the dean is up against mounting pressure from both sides. There’s a quietly growing sentiment among seminarians to resist the will of the government, and it gains strength with every new arrival, including two new students, longtime friends Juraj (Samuel Skyva) and Michal (Samuel Polakovic). In addition, one of the faculty, Fr. Coufar (Vladimír Obsil), has been holding meetings with students to discuss religious teachings that have not been sanctioned by authorities, as well as “secretly” performing unauthorized ordinations. To help counteract these developments, seminary administrators have appointed confessors to work with the students, such as the kindly yet often-exasperated priest (Milan Mikulčík) assigned to Juraj and Michal. All of which has attracted the increased scrutiny of Dr. Ivan and his minions, raising the tension within the institution to a discreet but palpable level.

The strain mounts on everyone as the story plays out. It seems as though nobody is doing (or able to do) what he wants. They have all become “servants” to ideologies and/or institutions with which they have issues. Do they truly believe in what they’re doing, or are they just going through the motions to save their hides? And at what costs does all this come? Their futures are in question. Their integrity, reputation and personal karma are all on the line. Even their psychological well-being and physical health are in jeopardy, as evidenced, for example, by the worsening and uncomfortable dermatological issues Dr. Ivan faces over time. Is this indeed service in support of a noble cause? These are the many questions that those caught up in this toxic scenario must sort out for themselves.

When one pursues a calling in a philosophical discipline like the priesthood, it’s incumbent upon those who do so to follow the teachings, traditions and messages of said vocation. After all, the dissemination of ideas – especially uplifting and empowering ones – is at the heart of what this undertaking is all about. This is particularly important in a repressed society, where the people need hope and comfort when under the thumb of totalitarian rule. Indeed, why would one pursue such an innately virtuous venture only to end up shortchanging one’s principles, essentially lying to oneself and engaging in compromised practices that are in service to an institution whose existence and purpose fly in the face of what one initially sought to accomplish?

That’s what the seminary faculty and students are being asked to do here. Telling parishioners what the government wants them to hear is the mission they’ve been tasked with, a trade-off to allow the institution to remain open. But is such a practice realistic? Can the seminarians live with themselves under such coercive conditions?

This is where looking to one’s heart comes into play, especially the beliefs that govern our conscience and actions. Understanding this essential, because it’s crucial to how our reality will unfold, thanks to the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains these resources dictate the nature and direction of our existence. And this consideration is integral to situations where intentionally seeking the desired manifestation of one’s mindset is fundamentally at the heart of the undertaking.

In a context like religion, for instance, this premise is central for being honest with oneself, to live life with a sense of integrity and personal truth. Those who minister to their parishioners are meant to set an example for them in hopes that they will follow suit. But that’s far from easy when these spiritual practitioners are being forced into doing so with their hands tied. How can they deliver inspirational messages of empowerment when authorities specifically tell them that they can’t because such notions conflict with official government dictates? The “service” the seminarians were meant to provide is essentially co-opted, replaced by dogma that blatantly contradicts the teachings they were meant to impart.

As a result, the seminarians are effectively being asked to seriously compromise their beliefs. The moral dilemma in this thus places a heavy burden on their shoulders. It again raises the question of how can they live with themselves? And, in turn, what are they supposed to do about it?

Of course, if we use our beliefs to create our reality, then one might legitimately ask, why would anyone want to create dicey circumstances like these in the first place? That’s a good question. But, if we look to the conditions under which Jesus lived His life, there are some uncanny parallels. Maybe the Czechoslovakian seminarians are having to relive Christ’s experience as a means to drive home His teachings in a society where the prevailing conditions are not all that different from those under which the prophet himself lived. Circumstances sometimes have a tendency to remain unchanged over time, and often the only way to bring about reform is to challenge them directly, as the seminarians do here. This is not to suggest that it will necessarily be easy, but making such an effort may be the best means for implementing transformation. One could say that this may be the most earnest way of being a servant to the cause to help bring about the implementation of these notions, challenging though the process may be.

Ironically, those seeking to impose their will upon the seminarians are themselves slaving away as servants in their own right and not necessarily in the furthering of a just cause. Individuals like Dr. Ivan, for example, dutifully carry out their missions, but at what cost? Are they truly fulfilled in what they do, spending their days propping up a brutal and corrupt regime? And in exchange for what – a better apartment or a few perks denied to the average citizen? Is that worth it, especially when one sees what it’s doing to them? One need only look to Dr. Ivan’s health issues to see what his brand of servitude is doing to him. One can’t help but wonder how long he’ll be able to keep doing what he does until the effects overtake him, especially if he knows deep down that what he’s doing is fundamentally wrong.

In the end, the only way to effectively resolve these conundrums is to get honest with ourselves – and that applies across the board in this scenario. The question, of course, is, can those in the seminary and officialdom bring themselves to do so? Can they take a good, hard look at their beliefs, see where they’re in need of alteration, and then implement measures to change them to correct these circumstances? It depends on how adept they are at following their hearts and how ready they are to be their true selves and live their lives with integrity. It may well be an ambitious undertaking, but it’s one truly worth considering, given that their souls might be at stake.

Chilling and thoughtful, director Ivan Ostrochovský’s second narrative feature spins an edge-of-your-seat tale while simultaneously delivering an insightful meditation on what it means “to serve.” This high-stakes morality play is a tale told in the shadows, one perfectly suited to the picture’s magnificent black-and-white cinematography, which alone is worth the price of admission. The eloquent framing of each shot and the filmmaker’s masterful execution of the picture’s mise-en-scène element are among the finest I have ever witnessed, and they enhance the storytelling by skillfully embellishing the actions playing out on screen. Some may find the pacing somewhat sluggish, but this deliberately employed tactic significantly adds to the slowly simmering narrative, upping the tension as events unfold. What I most liked about this offering, however, is the deft handling of the themes that underlie the principal storyline, adding a level of depth that takes the film to an entirely different level. It’s unfortunate that “Servants” has not received wider play or recognition than it has thus far, but, now that it’s available for streaming online, here’s hoping it garners the attention it genuinely deserves.

The incidents depicted in this film may have happened some years ago, but it behooves us to remember the kinds of events that were once commonplace. As recent history has all too clearly shown us, actions we may have naïvely come to consider unthinkable can rear their ugly heads quickly and with devastating results. That’s what makes films like “Servants” so important – they remind us of what we have and how preciously we must guard whatever gains we have made. Should we take those developments for granted, we could be in store for losing them, an undeniably rude awakening in which our very ability to think for ourselves and believe what we want to believe may be put on the line. Indeed, if we take such things for granted, we could end up becoming the kinds of servants on display here. And who would truly want that?

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment