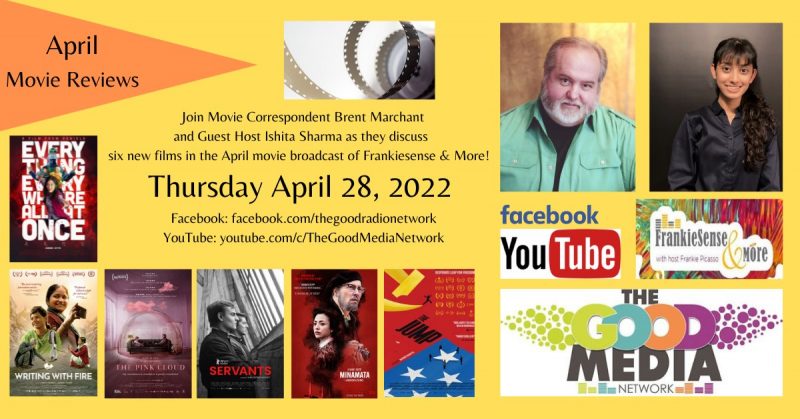

Reviews of six new films are now on the latest Frankiesense & More video podcast with host Ishita Sharma and yours truly, available by clicking here.

Reviews of six new films are now on the latest Frankiesense & More video podcast with host Ishita Sharma and yours truly, available by clicking here.

Join guest host Ishita Sharma and yours truly for this month’s new movie fun on Frankiesense & More! Tune in beginning Thursday April 28 on Facebook or YouTube for all the fun and lively discussion!

Tune in for the latest Cinema Scribe segment on Bring Me 2 Life Radio, beginning Tuesday, April 26, available by clicking here. You can also catch it later on demand on Spreaker, Spotify, Apple, iHeartRadio, Google Podcasts, Castbox, Deezer, Podchaser and Jiosaavn.

“Brighton 4th” (2021 production, 2022 release). Cast: Levan Tedaishvili, Giorgi Tabidze, Nadezhda Mikhalkova, Kakhi Kavsadze, Laura Rekhviashvili, Tsutsa Kapanadze, Temur Gvalia, Tolepbergen Baisakalov, Irma Gachechiladze, Mary Caputo, Lew Gardner, Yuri Zur. Director: Levan Koguashvili. Screenplay: Boris Frumin. Web site. Trailer.

How far can one’s sense of compassion and helpfulness extend? In an age of rampant self-absorption, that’s a good question. So many individuals today are preoccupied with their own needs, wants and whims that they may be wholly dismissive of such commendable qualities. At the same time, though, there are also remarkably sympathetic souls who will readily go to the wall for others, gestures that those who are less considerate may look upon as strange or even unfathomable. Thankfully, however, those admirable kindhearted oddballs are still around, as seen in the charming new comedy-drama/character study, “Brighton 4th.”

Kakhi (Levan Tedaishvili), an aging onetime Georgian wrestling champ, never seems to stop quietly caring about others. He lives a modestly comfortable life in Tbilisi with his wife, Maka (Laura Rekhviashvili), who spends much of her time bedridden (and who Kakhi lovingly attends to). But she’s not the only one he cares for. As best he can, he also tries to help out his brother (Temur Gvalia), who has a gambling problem, often frittering away hard-earned funds intended for more important purposes. But the one he’s most concerned about is his son, Soso (Giorgi Tabidze), who has relocated to New York – and whom Kakhi hasn’t heard much out of for some time.

Concerned and curious about what’s going on with Soso, Kakhi decides to visit him. Soso’s purpose in moving to New York was to study medicine and become an American doctor. However, when Kakhi arrives, he finds the situation is not what he believed it to be. Soso lives in a shabby boarding house run by Kakhi’s sister-in-law, Natela (Tsutsa Kapanadze), in Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach neighborhood, home to many émigrés from Russia and other former Soviet states. Instead of studying for exams, Soso works for a moving company, trying to earn enough money to pay off a $14,000 gambling debt owed to Amir (Yuri Zur), a local mafioso. He’s also attempting to raise cash to bankroll a green card wedding to Lena (Nadezhda Mikhalkova), a Georgian immigrant who’s become a naturalized citizen, so that he can legally stay in the US. But, despite his efforts at getting back on his feet, Soso keeps digging a deeper hole for himself due to his uncontrolled appetite for playing cards (and not very well).

Needless to say, Kakhi is quietly disappointed by what he sees. However, as the loving father he is, he wants to help his son turn things around. What’s more, as the newest resident of Brighton Beach, he’s eager to help the cadre of other colorful Georgian immigrants who live in his boarding house and the surrounding neighborhood, doing whatever he can to be of service. For example, he freely comes to the aid of Nana (Irma Gachechiladze), a cleaning woman who hasn’t been paid in months by her Kazakh hotelier boss, Farik (Tolepbergen Baisakalov), an encounter in which Kakhi’s muscular prowess as a former wrestler proves quite useful. He’s also willing to get creative in the measures he employs to be of help, as seen in a hilariously unconventional confrontation with Amir.

Through it all, Kakhi is a good friend to everyone he meets, doling out wise advice to those in need of it, such as Lena and Sergo (Kakhi Kavsadze), an elderly singing maître-d who lives in the boarding house. In line with this, he does whatever he can to ease the pain of others, as seen in conversations with Maka and Natela in which he smilingly assures them that all is well with their loved ones. His tactics may involve stretching the truth a little (or even a lot), but his concern for sparing others’ feelings is paramount with him. He’s also quick to forgive, especially when he can tell that others are sincere in their desire for atonement, engaging in acts of compassion and tolerance toward them that most of his cohorts are not so willing to dispense.

At the same time, Kakhi is nobody’s fool, either, and he’s not inclined to indulge those who take advantage of his kindness and good graces. This becomes apparent when Natela secures a job for him as a caretaker for an elderly couple, Tsilya (Mary Caputo) and Simon (Lew Gardner). Kakhi accepts the position in good faith, but he soon sours on it when Tsilya shamelessly comes onto him, often in front of Simon, acts that bewilder her husband and offend her new caregiver. Needless to say, the job doesn’t last long.

Such selflessness is indeed admirable, but, then, that’s who Kakhi is. But, given the magnitude of what he takes on, can he realistically work miracles every time? That’s what gets put to the test in this odyssey in New York. Indeed, Kakhi is used to “wrestling” with challenging circumstances; it’s something he’s done all his life, in various forms and generally quite successfully. But can he make it happen again?

The world could use more souls like Kakhi, especially these days. The acts of individuals like him are truly laudable. What’s perhaps most impressive, however, is how naturally these gestures seem to come to them. They step in without question, providing compassionate assistance when needed, with nothing expected in return. They genuinely embody the notion of the Samaritan whenever honest, honorable help is required. That’s the key in understanding them, for this is what constitutes their true selves. And, as their true selves, this is what enables them to carry out their deeds so successfully. They sincerely believe in what they’re doing, a point crucial to the unfolding of their existence, for their thoughts, beliefs and intents shape their reality. This is a result of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we tap into these resources in the creation of the world we experience.

Being true to ourselves is integral to manifesting the reality we desire. By drawing upon belief reserves driven by our honesty and integrity, we come closer to achieving our aspirations, and that’s especially true – and beneficial – in matters of compassion. It enables us to be the individuals we truly want to be, and it shows in the results, as it very much does with Kakhi.

In many instances, pulling off such acts of selflessness requires us to be both courageous and creative, qualities readily apparent in how Kakhi operates. As he tackles the challenges before him, he never shies away from them. And, if he needs to take an unconventional approach to how he proceeds, he’ll avail himself of the creativity required to make it happen. His use of these attributes in his various ventures thus provides us with examples of how to proceed in our own undertakings as the need for them arises.

In Kakhi’s case, his actions and their underlying beliefs illustrate what it means to be devoted to those we care about, our family and friends. As our companions on this journey we call life, they’re the ones who matter the most to us, and it’s best to demonstrate that in our acts and deeds. Kakhi understands this and thus knows what it takes to make life truly fulfilling. We should all follow his lead to make our – and their – existence more rewarding, even when circumstances take a downward turn. Life can indeed be redeeming, even if we’re not the ones to bring it about on our own, so it’s at times like these when we can be thankful for the Kakhis in our lives.

That’s what director Levan Koguashvili’s third narrative feature explores in this heart-tugging comedy-drama/character study. The film’s carefully crafted portrait of its Samaritan protagonist shows how it’s possible to help make things right for others, no matter what it takes, including the employment of everything from “polite” physical intimidation to telling “good lies” to assuage tender feelings. The result is a touching tale that stirs an array of viewer emotions, feelings brought out by the fine performance of Levan Tedaishvili, himself a former Olympic wrestling champion turned actor appearing here in only his second screen role. While the narrative tends to meander somewhat at times, the pieces that make up this story nevertheless collectively depict a close-knit community, with Kakhi at the center, made up of individuals who support one another through thick and thin and still rely on such traditional conventions as good faith and personal honor, even in dealings of a shady nature. We can learn a lot from that in a day and age when such values have come to be seen as outmoded and sentimentally quaint, a lesson that can help us wrestle with life’s challenges while maintaining an honorable sense of dignity and decency.

“Brighton 4th” has primarily been playing the film festival circuit, though it is now available for streaming online. Along the way, the picture has been well received by critics and viewers, especially in New York, the setting of the story. At the Tribeca Film Festival, this offering came up a trifecta winner in the international narrative feature competition, capturing the event’s awards for best picture, actor (Tedaishvili) and screenplay. That’s quite an accomplishment for a film that was cast with mostly inexperienced and nonprofessional actors, a true testament to the strength of this release.

We can all use a little help from time to time, and we should be thankful when individuals like Kakhi cross our paths. His kind of help exemplifies the altruistic principles depicted in films like “Pay It Forward” (2000), wherein assistance flows freely from us, with no expectations in return (even though the good feelings that come back to us often provide us with sufficient reward in their own right). It makes life in places like Tbilisi and Brighton Beach that much more manageable, especially under the challenging conditions their inhabitants must often endure. And that, in itself, can make life more worth living.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Reviews of "Writing with Fire," "The Pink Cloud" and "Minamata," along with podcast and blog previews are all in the latest Movies with Meaning post on the web site of The Good Media Network, available by clicking here.

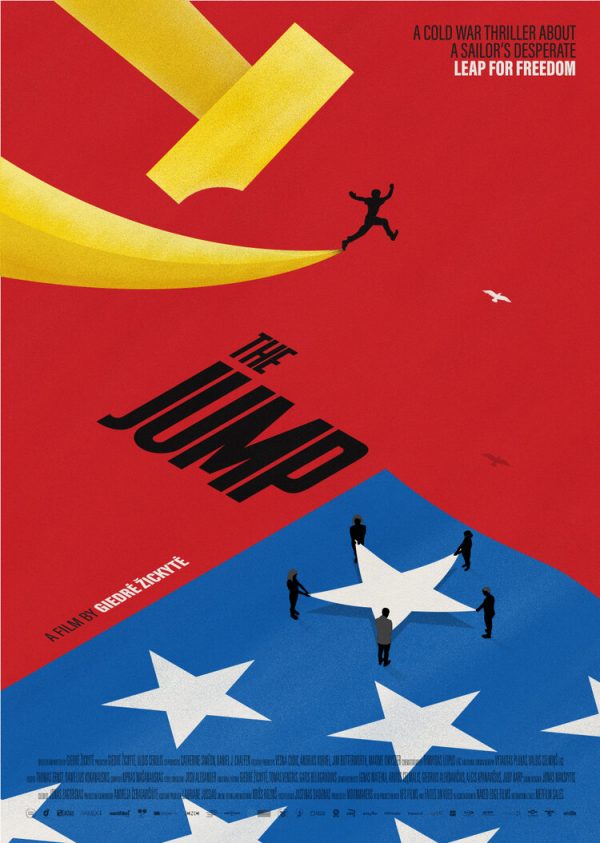

“The Jump” (“Suolis”) (2020 production, 2022 release). Cast: Interviews: Simas Kudirka, Henry A. Kissinger, Ralph W. Eustis, Paul E. Pakos, Vytautas Urbanas, Grazina Paegle, S. Paul Zumbakis, Barbara Korman. Archive Footage: Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley, Frank Reynolds, Robert M. Brieze, Robert P. Hanrahan, Fletcher Brown, William B. Ellis. Director: Giedrė Žickytė. Screenplay: Josh Alexander and Giedrė Žickytė. Web site. Trailer.

Have you ever considered taking a leap of faith to achieve a cherished goal? It takes courage. It takes conviction. And it takes a reasoned appraisal of our chances of success. But, no matter how thoroughly we examine the circumstances, there’s still a bit of a gamble involved, and that’s where the element of faith genuinely comes into play. How often is it, though, that the leap in question is both literal and figurative? So it was for an ambitious asylum seeker in the new Lithuanian-American documentary production, “The Jump” (“Suolis”).

For years, Simas Kudirka served as a radio operator aboard the Soviet trawler Sovietskaya Litva. When he wasn’t aboard ship, he lived with his family in the Soviet state of Lithuania, but he longed for the freedom that he believed awaited him outside the USSR. He hoped for an opportunity to avail himself of that prospect, and, amazingly enough, it finally arrived on November 23, 1970 off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts.

While the Sovietskaya Litva was moored in American waters adjacent to the US Coast Guard cutter Vigilant for a diplomatic conference about fishing rights, Kudirka scanned the distance between his ship and the American vessel. Kudirka was sizing up what it would take to jump ship and land on the deck of the Coast Guard cutter. As he did this, an American sailor watched Kudirka, trying to determine his intentions, an assessment that went on for several hours. And, by late afternoon, the courageous radio operator made his move, jumping the 12-foot span separating the trawler and hoped-for freedom.

Once on the American vessel, Kudirka requested political asylum, but the Vigilant’s crew was unsure how to respond. The ship’s commanding officer, Ralph W. Eustis, and his lieutenant, Paul E. Pakos, assessed options and eventually contacted Rear Admiral William B. Ellis for guidance. Somewhat surprisingly, Ellis refused Kudirka’s request and ordered him returned to the Soviets, despite the asylum seeker’s presence on an American vessel in US waters. He allowed a team of six Soviet sailors onto the Vigilant to retrieve the would-be defector, who was beaten and extracted back to the trawler. Kudirka was then returned to the Soviet Union, where he was tried for treason and sentenced to 10 years in a gulag.

So much for Kudirka’s hopes of freedom. Or so it seemed. Before long, it became apparent that all was not lost.

When word of the incident made it into the American press, considerable outrage arose over its handling. The story’s widespread coverage in print and on national news broadcasts incensed many in the general public, especially in the Lithuanian immigrant community. Many of Kudirka’s American émigré countrymen took up the fight on his behalf, petitioning the support of influential politicians like Congressman Robert P. Hanrahan (R-IL), who fought for the seaman’s release. Even high-ranking officials, like Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger and President Richard Nixon, criticized the handling of the incident and sought restitution.

But, even with such high-powered support, Kudirka’s big break came from an unlikely source. When a Lithuanian émigré discovered that Kudirka’s mother was born in Brooklyn before returning to her homeland with her family, it became immediately apparent that Simas had an entitlement to American citizenship by virtue of his mother’s birthright. American officials pressed the issue with the Soviets, who shortly thereafter released Kudirka from the gulag. In no time, Simas and his family were on their way to America and a new life.

Once in the US, Kudirka spent time in New York, New Jersey and California. His story was made into a TV movie, “The Defection of Simas Kudirka” (1978) with Alan Arkin, Richard Jordan and Donald Pleasance. And he lived a colorful and productive life, trying his hand at various vocations and relishing the benefits that freedom had afforded him. But, once widowed, he felt a void open up in his life, which he sought to fill, somewhat successfully, by returning to a now-free Lithuania, where he has since settled down into a comfortable and content retirement.

Through this remarkable odyssey, Kudirka has set an inspiring example for all of us in myriad ways – how to live courageously, how to seek fulfillment out of life, how to appreciate what we have and how to cherish the freedoms that many of us take for granted. It’s been quite a full life, one to which we should all aspire. And all it took was a leap of faith.

What Kudirka did is something that more of us should probably do. After all, as it has often been said, when we come to the ends of our lives, we generally regret the opportunities we didn’t take more than those that we did that failed. That’s particularly true for the big decisions that come along, those that represent significant turning points in our lives. Given that they can greatly alter the course of our destinies, they should be considered carefully and, when needed, boldly, just as Simas did.

So how did the hopeful seaman come to this decision? It came about as a result of his beliefs, specifically those associated with his realization that he could do this. That’s important, given that our beliefs – whatever they may be – govern the unfolding of our reality, a result of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in the manifestation of our existence. And, even if Kudirka had never heard of this school of thought, it’s apparent from the way things turned out that he was obviously well versed in its principles.

For his part, Kudirka courageously pursued this venture despite the risks. He faced dire consequences if he were to fail. The leap in itself was not an easy feat, and, if he were to be refused his request, he would have to address the fallout from brutal, intolerant Soviet government authorities. Indeed, considering the stakes involved here, there was a lot riding on his actions and their underlying beliefs and whether he could realistically make them work in his favor. Yet, despite it all, he had faith in himself and his beliefs, with the hope that it would carry him through. This may not have been enough in and of itself, but it certainly gave Simas a solid starting point from which to work.

This undertaking required Simas to, first, assess his fears and the limitations he was up against and, then, decide whether he could successfully overcome them. He also had to consider what he was going to do if his plan failed, an outcome that came to pass, at least initially. Such a prospect raised an array of new challenges, such as his interrogation by the KGB, the Soviet security agency, and its often-ruthless investigators, such as Vytautas Urbanas, who’s steely resolve becomes quite apparent during one of the film’s interviews. The pressure on Kudirka at the outset of this saga was severe enough, but it became even greater after events began playing out.

This, of course, backed Simas into a corner, calling for inventive measures to turn his situation around. It forced him into becoming even more creative in his beliefs and what he hoped they would yield for him. That undoubtedly had to be difficult in light of the circumstances under which he was operating, namely, the deplorable conditions of the gulag, which are graphically depicted in the film. But, despite everything seemingly working against him, Kudirka managed to manifest the means to help to make his plans unfold as hoped for.

First, there was the zealous backing of his devoted supporters, including everyone from his émigré countrymen to high-profile politicians, an excellent example of co-creation at work. Then there was the open acknowledgment that the handling of Kudirka’s situation was in error and in need of rectification. But, perhaps most importantly, there was the “lucky” break that the asylum seeker was legitimately justified in pursuing his goal. By availing himself of the synchronicities that came his way, Simas found a way and made the most of it.

To a great degree, Kudirka’s success in this matter rested with his sincere desire to attain it. Achieving freedom was something he earnestly wanted, a reflection of his true self and the core beliefs at its center. When we tap into this aspect of our being, we significantly increase the likelihood of fulfilling our goals, mainly because they arise from a genuine sense of truth, honesty and integrity.

With these qualities driving the process, our chances of successful fulfillment are thus tremendously enhanced, even if they don’t necessarily seem that way at first. However, setbacks need not be a death sentence; they can often serve to strengthen our resolve, to galvanize our feelings, to bolster our commitment. And, when our adversaries are forced into confronting such circumstances, they had better beware of what they’re up against, as Kudirka so cunningly demonstrates in his inspiring story.

The taste of success in scenarios like this can be quite sweet, And, given what Simas gained as a result of his initiative, he developed a significant degree of appreciation and gratitude for his newfound fortunes. For those who have experienced the lack of abundance and personal flexibility that Kudirka endured, it should come as no surprise that such grateful outlooks would result. During his time in America, Simas tried to impress this view upon a society that had lost sight of this, encouraging the unappreciative among us to renew and embrace this outlook. That may call for some of us to take a leap of faith of our own, but it’s one that can leave us fulfilled and liberated – not unlike Simas himself.

Taking a leap of faith – literally and figuratively – is a truly inspiring act, especially when we believe that doing so will help us fulfill a cherished dream. The heartbreaking and heartwarming saga of this enlightened asylum seeker takes viewers on a rollercoaster ride as we witness his remarkable journey to freedom. Director Giedrė Žickytė’s in-depth documentary about this incredible odyssey tells a compelling tale that not only outlines the events of Kudirka’s courageous crusade, but also presents an up-close profile of a colorful and vibrant individual, one who shows us our lack of appreciation for things that we should be valuing, as well as how to stay vital well on into our senior years. It’s a combination of elements that generally works well, although the final segment loses some steam as the picture winds down to the final frame. Nonetheless, even though this is a story that has largely gone forgotten, it delivers a message that should never be.

At present, finding this film may take some effort. “The Jump” has primarily been playing the film festival circuit, which it will probably continue doing for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, it’s a title worth searching for, especially since many of these screenings have been accompanied by insightful Q&A sessions with the director after the film. There’s more to this story than what appears on the screen, and these discussions bring that to light in intriguing and uplifting ways.

Anything worth having is truly worth fighting for. That’s particularly true for those precious freedoms that so many go without and that those who possess them often take for granted. Kudirka’s story shines a bright light on the foregoing, one whose value shouldn’t be underestimated. At a time when such liberties hang in the balance – even in places where they’re supposedly guaranteed – we must remain steadfast about their protection and preservation, especially when we consider the alternative – and what it might deprive us of.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

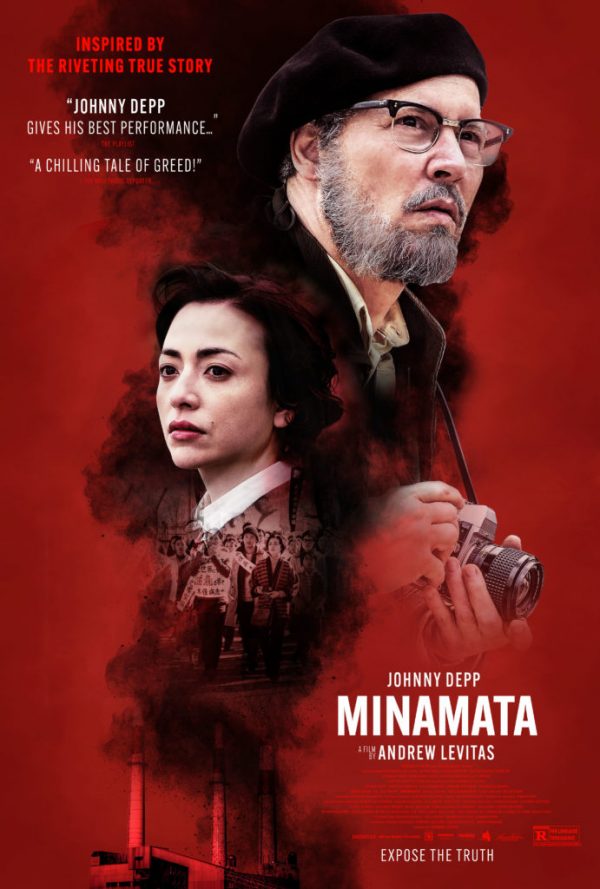

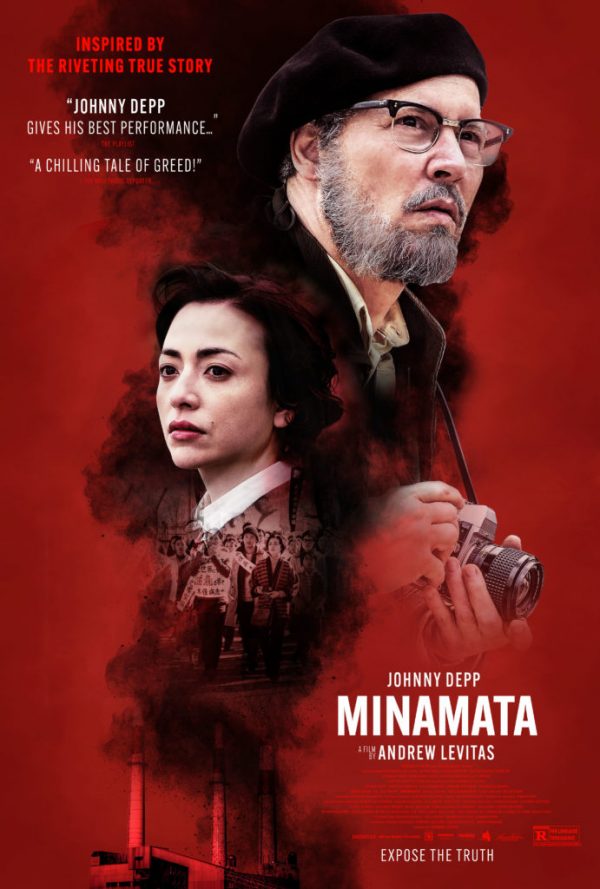

“Minimata” (2020 production, 2022 release). Cast: Johnny Depp, Bill Nighy, Minami Hinase, Akiko Iwase, Tadanobu Asano, Kogarashi Wakasugi, Jun Kunimura, Hiroyuki Sanada, Ryô Kase, Yosuke Hosoi, Katherine Jenkins. Director: Andrew Levitas. Screenplay: David K. Kessler, Stephen Deuters, Andrew Levitas and Jason Forman. Book: W. Eugene Smith and Aileen M. Smith, Minamata: The Story of the Poisoning of a City, and the People Who Chose to Carry the Burden of Courage (1975). Web site. Trailer.

When we’re past what we think of as the top of our game, we may grow despondent, disillusioned and withdrawn, perhaps believing that we’ll never get back what we’ve lost. It can be a frustrating and depressing time, one that leaves us sorely wanting. Can the redemption we seek be attained, or is it really too late? That’s the question posed in the new fact-based historical drama, “Minamata.”

In 1971, acclaimed photojournalist W. Eugene Smith (Johnny Depp) had fallen on hard times both professionally and personally. Smith established himself through his coverage of the Pacific theater during World War II, capturing images of the battles of Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa, which were featured in LIFE magazine. Through this work and other assignments, he made a name for himself as the father of the modern photo essay, widely recognized as one of the pre-eminent practitioners in the business.

In the years after the war, though, Smith’s fortunes began to fade. As a free-lance photographer, many of his projects didn’t pay off as planned (despite the critical acclaim many of them received). He became financially strapped, living under destitute conditions in a run-down New York apartment and even selling some of his equipment to raise cash. He had become estranged from his family, having not spoken with his children in years. He grew increasingly dependent on alcohol and amphetamines, putting a severe strain on his health and making him notoriously unreliable. And he developed a reputation for being difficult to work with, prompting many onetime collaborators, like LIFE magazine editor Bob Hayes (a pseudonym created for the movie) (Bill Nighy), to avoid new assignments with him. For all practical purposes, at age 52, Smith had come to see himself as washed up with virtually no future and little hope for redemption.

That changed, however, when he took on a job with Fuji Film, a project that brought him into contact with translator Aileen Mioko (Minami Hinase), who used her position as a springboard to make contact with the photographer. She knew of his reputation for creating works that would get noticed and hoped that she could convince him to accept a project in need of the kind of attention he could generate through his photos. Although initially resentful of having been railroaded, Smith nevertheless was willing to give a listen to her proposal. And, after she explained what she was after, it completely turned him around.

Aileen told Smith about the plight of the Japanese fishing village of Minamata, where the residents had been systematically poisoned for at least 15 years by the Chisso Corporation’s practice of dumping mercury into the waters surrounding the community. The result was widespread illness among the locals – some of whom had been sickened while still in the womb – with a condition characterized by multiple symptoms that had come to be known as “Minamata disease.” Yet, despite how prevalent the illness had become, few outside of Minamata knew anything about it. Media coverage had been scant, and Chisso, as the responsible but powerfully influential party in this situation, had managed to successfully keep the story under wraps.

If circumstances were ever going to change, the world had to hear about this unspeakable atrocity, and Aileen believed Smith was just the person to tell this story. And, to that end, she made a convincing enough case to win over his support. Smith pitched Hayes about covering the story for LIFE, which, like the photographer, was itself fighting for survival at the time. And, before long, Smith was on his way to Japan.

Smith’s return to the Far East came with mixed feelings in light of his war experience. He saw tremendous carnage during his years on the battlefront, and he had been severely injured at one point. However, he knew the Minamata incident was a story that had to be told, and so he managed to set aside his painful memories as best he could to take on this new assignment, one that could well be his last and one that just might give him that shot at redemption that he so desperately sought.

Once in Minamata, Smith had an opportunity to see the impact of the illness firsthand. One of his first experiences was meeting the Matsumura family, through whom he witnessed the heart-wrenching but loving care provided by parents Masako (Akiko Iwase) and Tatsuo (Tadanobu Asano) in tending to their severely afflicted daughter, Akiko (Kogarashi Wakasugi), who had been affected by the disease while her mother was pregnant. It nearly tore up the gruff, hard-nosed journalist, but it also affirmed his conviction to get the story out. If someone as jaded and cynical as Smith could have his head turned, then it was obvious morality wasn’t dead. Indeed, the world needed to know, and those responsible needed to pay.

Subsequently, Smith met some of the activists struggling to raise awareness, including the initiative’s outspoken, charismatic leader, Mitsuo Yamazaki (Hiroyuki Sanada). He also met an advocate who was a fellow photographer, Kiyoshi (Ryô Kase), who was experiencing the first stages of Minamata disease. Kiyoshi somehow managed to control the characteristic shaking associated with the illness whenever he snapped a picture, demonstrating his firm resolve for making sure this story was told – and inspiring Smith even more.

On the flip side, Smith also met Junichi Nojima (Jun Kunimura), president of Chisso. Drawing upon his polished professional demeanor (and backed by the muscle of a pair of beefy body guards), Nojima attempted to whitewash the circumstances, painting a glowing picture of all the good his company was doing and repeatedly emphasizing how infinitesimally small the pollutant discharges were. He even went so far as to offer Smith a hefty bribe to walk away from the story. Yet, no matter how hard he tried to sway Smith’s opinion, he failed at every turn.

As Smith and his colleagues persisted and continued to turn up the heat, their task grew ever more difficult. They were bombarded by the same kinds of manipulative and strong arm tactics that Chisso had tried to use in silencing Minamata residents whenever they tried to press their case with the corporation or to make their plight more widely known. And, admittedly, the corporation had some success in their efforts, wearing down the townsfolk and Smith to the point where they had to consider whether the effort was still worth it. But, for Smith’s part, he had promises to keep – to Aileen, to the residents of Minamata, to Bob Hayes, and, most of all, to himself. He had to keep going – and so he did.

Making up for past missteps is often an ambitious, heartfelt goal, one that we feel compelled to address, even if we’re not sure how or whether our efforts will measure up. We may end up placing so much pressure on ourselves that we feel paralyzed or throw in the towel. But, with such feelings hanging over us, we may never feel completely satisfied, no matter which course we pursue. If we’re ever to get off the dime, we need the right spark to bring us back to life and set us on a course where restitution in some form or another is possible.

These are the circumstances under which we see Smith wallowing as the film opens. He seems to want to make amends for his past, but he often feels hopeless, and, with the clock ticking, he’s not sure he’ll be able to address this matter within the time frame he has left. But, just as he’s about to give up hope, something unexpected and miraculous drops in his lap, providing him with an opportunity to make things right. He may not be able to completely erase the mistakes of his past, but he can at least take steps that enable him to feel fulfilled and worthy, an accomplishment brought to life by his own acts and deeds.

More importantly, though, Smith wrought this achievement as a result of his thoughts, beliefs and intents, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we tap into these resources in manifesting the reality we experience. By drawing this opportunity to him, Smith opened a door to the redemption he had been seeking for some time, and, as this story shows, he pounced on it.

The success Smith attained came about for various reasons. For starters, Smith was being faithful to his true self. Even though he often appears to be an embittered, surly curmudgeon who has engaged in some questionable behavior throughout his life, he nevertheless has a strong moral core, genuinely concerned with matters of right and wrong and seeing justice served. This mindset played a significant role throughout his career, including in the subjects he chose to document through his work. So, when the Minamata story crossed his radar, he jumped at the chance to tackle it, even stirring up considerable enthusiasm among the LIFE magazine editorial staff at a time when the publication’s viability needed a hefty adrenaline shot to bolster its flagging fortunes.

In pursuing this endeavor, Smith had some hurdles to overcome, particularly in the areas of fear and limitation. He had his share of personal demons to address, too, some related to his own actions and some tied to his past experiences in Japan. He also faced more challenges once on assignment, including the manipulative and intimidating tactics employed by Chisso. But, if Smith were to succeed at this undertaking, he had to get past these obstacles, embracing beliefs that enabled him to live courageously in the pursuit of this just cause.

As someone who was accustomed to working solo, he needed to realize that this was likely no longer possible at this point in his career. He had to forge alliances with collaborators who could help him complete the task at hand. Fortunately, he was able to find colleagues who could assist him in gathering valuable evidence, opening doors to significant leads and bringing the truth to light, painting a more complete picture of the overall scenario. This effort thus represented a prime example of co-creation at work, where pooled input led to an outcome that proved even more illuminating than expected.

When assessing the role Smith played in this situation, it’s as if it were meant to be. As unlikely as that might have appeared at the start of this tale, Smith was the right person for the job. Considering the impact he had always had with his work and given what this story needed to make the public more aware of it, this was the perfect match between talent and need. One could call it destiny or, perhaps more precisely, a prime example of value fulfillment at work, the conscious creation concept associated with being our best, truest selves for the betterment of ourselves and those around us. The assignment served Smith’s professional and personal needs while bringing this health and environmental disaster to light. And, even though Minamata was the last project Smith undertook, it provided him with a heroic way to round out his career. We should all go out on such a high note.

No matter how old and detached we may become, it’s never too late to redeem ourselves, as this offering from director Andrew Levitas so effectively illustrates. This fact-based offering presents viewers with a classic “issues film” much in the same vein as “Erin Brockovich” (2000) and “Dark Waters” (2019), focusing on the personal angle of this catastrophe, showing its impact on the protagonist and victims in graphic yet heart-tugging terms. Admittedly, the tone can be somewhat heavy-handed at times, and there are some problems with an underdeveloped back story and an occasionally meandering script. But these issues are compensated for by the picture’s gorgeous cinematography, its superb Ryiuchi Sakamoto background score, and the fine lead performance of Johnny Depp, who turns in some of the best work he’s done in years. Indeed, despite the film’s tendency to preach, its message is nevertheless important – one that probably can’t be overstated in light of its impact and magnitude (and as only one example of many such ecological disasters that have occurred globally, as depicted in a montage of comparable events shown over the closing credits). This is genuinely something we must all remain diligent about, and, thankfully, that cause can be furthered by efforts like those shown here, reminding us that this planet is our home and deserves the kind of protection and respect that so many others have been willing to deliberately ignore.

Virtually everybody loves those who are able to make valiant comebacks, no matter what they may have done to put themselves in such compromised situations. It’s heroic, affirming and rejuvenating. It demonstrates an ability to fight for themselves, to bounce back when the odds are stacked against them. And it inspires us to do the same when comparable conditions arise. Indeed, we needn’t succumb to despair or a future without hope. There are always just causes worthy of being addressed – and we may just be the ones best suited to taking them on.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

“The Pink Cloud” (“A Nuvem Rosa”) (2021). Cast: Renata de Lélis, Eduardo Mendonça, Helena Becker, Kaya Rodrigues, Girley Brasil Paes, Gabriel Eringer, Lívia Perrone Pires. Director: Iuli Gerbase. Screenplay: Iuli Gerbase. Web site. Trailer.

Is it possible to see the “same” situation in two different ways? That’s an age-old question that’s been debated for eons by philosophers, theologians and even quibbling parents, each claiming that their view was “right.” But who’s to say that anyone is “wrong” in these quarrels? Maybe everyone is “right” about what they perceive, each driven by his or her individual beliefs. It’s a question brought up once again, this time in an unlikely context, as seen in the intriguing new Brazilian sci-fi offering, “The Pink Cloud” (“A Nuvem Rosa”).

What if we were to face circumstances where an outside danger was forcing us to stay inside, cooped up in isolation for a prolonged period? Wouldn’t it be interesting to speculate about what might happen as a result of that? And how might we view it?

Hey wait – we’ve already done that.

Nevertheless, it’s intriguing to see how closely reality paralleled the ideas raised in this piece of cinematic speculative fiction, which was written in 2017 and filmed in 2019, before the COVID pandemic began. The timing of its release in 2021 couldn’t have been more ironic and synchronistic. It certainly gave the picture’s marketing people something unexpectedly relevant to work with, despite claims that any similarities between the film and actual events were purely coincidental.

In this story, a mysterious pink cloud suddenly begins appearing around the world. Despite its pastel beauty, it’s deadly, apparently containing toxic gases that kill quickly, within moments of exposure. Because of this, everyone is hurriedly corralled indoors, forced to either shelter in place or find the nearest available enclosed space, decisions to which little thought is given in light of the situation’s pressing immediacy. Many are trapped in places like supermarkets, often among strangers, with no idea how long they’ll be confined. One thing is for certain, though: Those who take these hasty steps to secure themselves are guaranteed to survive (at least initially) as chilling televised reports reveal just how fast one can succumb to the effects of the cloud.

The nature of the cloud and its projected duration are a complete mystery. However, it soon becomes apparent that it has remarkable persistence, and everyone must begin making preparations for these conditions for the long term. And this is true both for survival provisions as well as the relationships among those who suddenly find themselves sequestered with one another, some of whom may have little familiarity with their new domestic companions.

Such is the case with Giovana (Renata de Lélis) and Yago (Eduardo Mendonça), who met only the night before the cloud’s appearance. They attended a club, where they connected and struck up an attraction that led to a one-night stand at the home of Giovana’s mother. When morning came, however, as they leisurely chilled in hammocks on the house’s balcony, they heard warning sirens blare with announcements advising everyone to move indoors as quickly as possible. And, in no time, the virtual strangers found themselves in close quarters for an unknown duration.

So what does one do under conditions like this? Well, considering that going outdoors would mean a death sentence, staying inside is the only viable option for anyone who doesn’t have a suicidal death wish. After taking an inventory of supplies and attending to other basic considerations, Giovana and Yago make video calls to check in with loved ones. Giovana calls her younger sister, Júlia (Helena Becker), who is attending a birthday party, and one of her friends, Sara (Kaya Rodrigues), who is home alone after her partner stepped out to visit a nearby bakery. Yago, meanwhile, calls his aging father, Rui (Girley Brasil Paes), who suffers from memory-related issues and is under the supervision of a live-in caretaker. They’re both concerned about the well-being of their family and friends, but, for now, keeping in touch is about all they can realistically do.

And so, after dealing with these initial adjustments to their routine, Giovana and Yago begin settling in to their new normal, unsure of what shape that will ultimately take. They attempt to address the issues that now present themselves, such as figuring out what course their relationship will take. Given how they met, it’s obvious there’s some degree of attraction between them, but is it enough to sustain them going forward, or were they just running on a surplus of hormones at the time? Do they share common goals for the future, or are they on different, potentially irreconcilable paths? Indeed, can they make this work?

Then there’s the question of grappling with long-term isolation and all of the attendant considerations that come with it, such as depression and other emotional issues. How well can each of them cope with being stuck within a limited number of walls? Granted they’re fortunate to be in Giovana’s mother’s well-appointed home, which offers an array of amenities and distractions, but will they be enough for the long term? And how well will the couple be able to cope with not having access to the big beautiful world just outside their windows, a view that ever tempts them to venture outdoors despite the known perils associated with that?

As the years pass and the relationship becomes more solidified, even more profound questions enter the picture, such as possibility of having children. What if Giovana and Yago aren’t on the same page about this? But what if children arrive anyway? Then what? How will the presence of another being in the household affect the balance of things? And what would children bring to the table, especially since they might have to spend their entire lives confined indoors?

These are among the issues that Giovana and Yago must face. As daunting as those who lived through the pandemic came to view their circumstances, they pale in comparison to what those in the world of the pink cloud must wrestle with. The prospect of having to endure such conditions for years is probably unfathomable to most of us, but that’s what the residents of this new existence are saddled with, and we can’t help but wonder how they’ll manage. This truly becomes a case of life being what we make it. But the big question here is, what will they create?

The closer one looks at this story, the more one sees that there’s much more going on than simply protecting oneself from a deadly threat. But understanding that may take some doing, including having to endure the circumstances for a time to realize what’s actually transpiring. And, on this point, the narrative here parallels what has happened in real life even more than what one might initially think.

In shaping their new lives together, Giovana and Yago draw on their beliefs in manifesting their own versions of what constitutes their new normal. That’s important to recognize, given that our beliefs are responsible for materializing our reality, the product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in framing our existence. And, considering that the protagonists are in many ways starting with a blank slate, they can aim for whatever they want, depending on whatever beliefs they have in place.

Much of the time, many of us tend to look upon this process in a somewhat piecemeal fashion, examining the manifestation of each of the components that make up the reality we experience. But, in this case, it’s hard to ignore the fact that Giovana and Yago are essentially rebuilding the totality of their existence, including the overarching qualities that characterize it. In that sense, then, they’re each actually materializing a template upon which all of their individual manifestations rest. Their templates are based on the perspectives they each embrace for their new reality, outlooks that are shaped by amalgamations of various beliefs, which, in turn, provide an underlying pattern for the creation of their new reality.

Cryptic though that may sound, we can actually look at our own experience to see how it’s reflected in the narrative of this film. Think of how many different ways life has changed as a result of the COVID pandemic. Remote working, for example, has become far more widely employed and accepted than previously. Breadwinners have become much more attuned to creating better work/life balances than in pre-pandemic times. Cocooning has replaced going out as a way of life for many individuals who were once social butterflies. The implementation of these changes wasn’t aggressively sought when they weren’t seen as necessary, but, when conditions changed, individuals embraced them, and their adoption resulted from wide-ranging changes in perspective (i.e., the new template).

As the story in “The Pink Cloud” plays out, we see the same happening to Giovana and Yago. After addressing basic needs like survival, through which they became more proficient as creative problem-solvers and learned how to overcome fears and limitations, they begin to assess what they want out of life as they settle in to their new routines. They each need to decide how they want to characterize them, figuring out which qualities they want to dominate. And, even though they’re in this situation together, they each have their own views of what they want, which means that they don’t necessarily share the same prevailing outlooks.

When an event like this occurs, there’s a fundamental sense of loss associated with it. The key to adapting, however, depends on how we see it. In many ways, this comes down to the question, is the glass half empty or half full? The half empty analogy no doubt arises from things like the inability to go outside and to interact with other people. It’s disappointing, to be sure, especially for those who have become accustomed to such activities. On the other hand, there’s the half full perspective, which rests on gratitude for things like one’s health, safety and continued existence in light of the prevailing circumstances. This view represents a basic appreciation for what one has, not what one lacks.

In light of what Giovana and Yago are up against, which of these perspectives is likely to offer a better chance of coping with the situation at hand? This is a lesson for them, just as it was for many of us with the onset of the COVID pandemic. The scenario thus operates as a refresher on the value of gratitude and appreciation, concepts that many of us lost sight of in a world that has grown selfishly obsessed with the notion of satisfaction on demand. When we have whatever we want, whenever we want it, we can grow unappreciative of what we do have while lamenting that which we don’t have (and that we can probably get along without just fine). Sometimes, though, it takes conditions like this to rediscover that lost awareness, and this film’s narrative provides us with a poignant reminder.

A key to grasping the foregoing rests with an ability to know when to let go, a point driven home at multiple times and in multiple ways during the film. Holding on when letting go would suit us better can be a hard choice, one that’s difficult to embrace palatable beliefs about. This is perhaps most obvious when it comes to holding out hope for being able to return outdoors, but there are even more painful choices to be considered. This becomes apparent when Giovana and Yago must come to terms with their level of contact with Júlia, Sara and Rui. Indeed, what’s one realistically to do when there’s essentially nothing to be done? How will one’s perspective be affected when false hope is allowed to continue to hold sway, particularly in situations where doing so accomplishes nothing? And, in turn, what impact would this have on one’s resulting reality?

In these regards, “The Pink Cloud” is more than an intriguing work of science fiction or a remarkably prescient depiction of recent everyday life. It delivers thoughtful insights on the nature and qualities of existence. It helps us see what makes life worth living, including under conditions of great duress. And it helps us to decide how we wish to approach it – or whether we even want to do so.

Director Iuli Gerbase is off to a great start in this debut feature. This Brazilian offering handily surpasses its sci-fi roots in its exploration of a host of philosophical, metaphysical and moral issues, such as acceptance of our circumstances, knowing when to let go and developing appreciation for what we have, even in the absence of what we’ve lost. Its gorgeous cinematography and pastel-dominated art direction give the film an ironically loving look, one that comes in stark contrast to the perpetually deadly threat that awaits on the other side of the windows. Admittedly, the film suffers from occasional pacing issues (especially in the second half), as well as some repetitiveness in certain aspects of the screenplay/narrative. Nevertheless, this release has much to say, not only about what we’ve experienced, but also in terms of what we should consider taking away from it – a message that we must remember was crafted before our recent circumstances materialized. The film is available for streaming online.

In watching this film, one might wonder how something so beautiful as the pink cloud could be quite so menacing. We’ve all no doubt witnessed gorgeous sunrises and sunsets where the skies have been filled with wisps in such gorgeous hues, and, through these experiences, we’ve never questioned the beauty that Nature has sent our way. So why should this instance be any different? Well, in a way, perhaps it’s not; perhaps the beauty here lies in the message accompanying this phenomenon, one intended to nudge us into a greater sense of appreciation and gratitude. It may be delivered in a seemingly backhanded way, but it’s nevertheless a case of the Universe practicing tough love for us, behaving as if it’s a stern parent trying to impress a message upon us that we’ve been unable or unwilling to grasp but that we truly need to hear. We should be grateful for that in and of itself. But, if nothing else, we can only hope that we have the awareness to see the wisdom that’s being imparted – and to make it the priority in our lives that it truly deserves to be.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

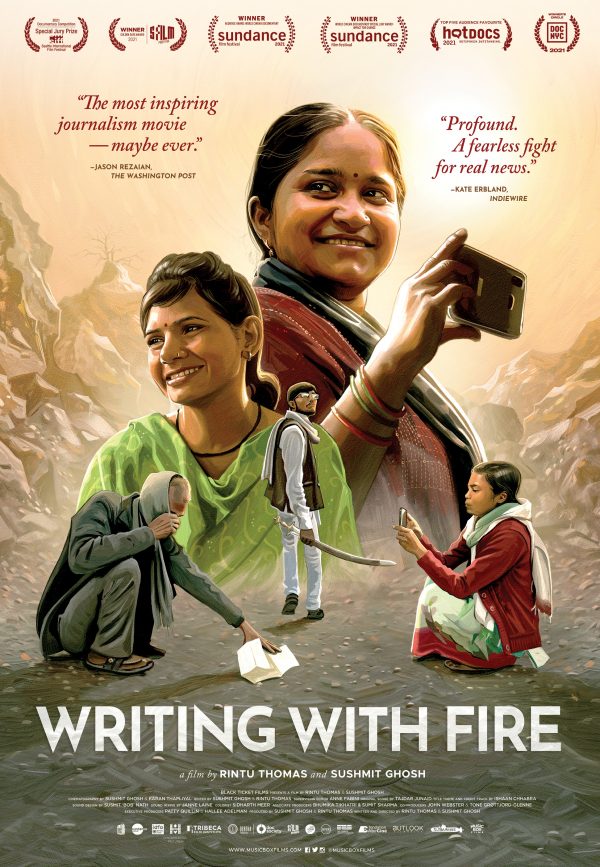

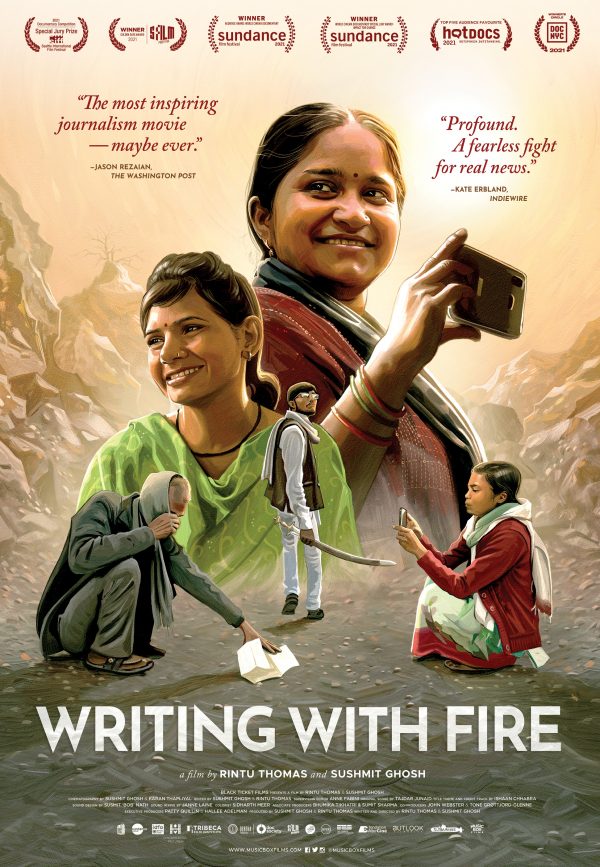

“Writing with Fire” (2021). Cast: Meera Devi, Shyamkali Devi, Suneeta Prajapati. Directors: Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas. Web site. Trailer.

Getting the truth into circulation when the deck is stacked against you is quite a challenge. In an age when corporate media have come to dominate the journalism landscape, it’s difficult to make inroads for organizations that don’t have ample resources or that don’t fit the expected mold. But, with determination, confidence and a staunch desire to succeed at delivering the truth, it may be possible to achieve a significant breakthrough, as depicted in the new Oscar-nominated Indian documentary, “Writing with Fire.”

Set in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, “Writing with Fire” profiles Khabar Lahariya (KL)(“Waves of News”), an independent news organization launched by a group of aspiring journalists in 2002. What distinguishes KL is the fact that it’s run entirely by women who come from the Dalit caste, often referred to as “the untouchables.” And, as a region that has many “media dark” areas, it’s often difficult for news to become disseminated to uninformed masses. What’s more, as a region known for its widespread corruption, its tolerance of violence and discrimination against women, and its strict adherence to maintenance of India’s rigid caste system, many Uttar Pradesh locals have trouble learning about what’s unfolding in their area. With conditions like these and a dearth of educational opportunities, it’s easy to keep the populace in the dark – just what those in officialdom want.

In telling KL’s story, filmmakers Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas enter the picture 15 years after the organization’s founding at a time when it was transitioning from a print outlet to an electronic news source to more widely disperse its output. With its team of 28 semi-literate reporters, the news staff was having to learn how to use a new technology (cell phones), a challenge given that many of them don’t understand the English operating instructions and don’t even have electricity in their homes. However, considering how far the team of journalists had come from their humble beginnings (and in the face of an array of challenges), they forged ahead with this change with the same degree of commitment and dedication that had gotten them to this point.

And what a level of success KL had attained. In a media world dominated by moneyed corporations and men with impressive educational pedigrees, the team of comparative amateurs diligently moved forward in making a name for themselves. What began as a venture that many believed was destined to fail, the organization has blossomed into a widely followed media outlet, with over 150 million viewers of its YouTube channel. The journalists have also demonstrated their perseverance in chasing down their stories, frequently at significant personal risk, both as women specifically targeted because of their gender and in having to obtain information from seedy, unreliable and dangerous sources. In carrying out this task, the women of KL have tracked down stories related to such topics as victimization against women, illegal mining, mob activity, corrupt and negligent government practices, insufficient infrastructure planning and programs, and the rise of right-wing political fundamentalist movements. At the same time, by drawing attention to these matters, KL has often helped to spread awareness of these issues and even spur on much-needed reforms.

KL’s story is personalized by focusing on three of its staff members. Chief among them is 32-year-old Meera Devi, the organization’s tireless principal reporter, who fought against relentless discrimination and a conservative culture to study journalism and become a professional practitioner. Meera’s feisty 20-year-old protégé, Suneeta Prajapati, who grew up as a child laborer in an illegal mine, has emerged as the only female crime reporter in the region, focusing much of her investigative efforts on the region’s lucrative illegal mining businesses and the corrupt nexus between the mafia and politicians. Then there are novices like Shyamkali Devi, who is learning the ropes while on the job, but it’s an undertaking that doesn’t deter her, carrying on despite the challenges to get the story out.

The personal side of this story also delves into the impact that this work has on the reporters when they’re off the clock (if such a thing actually exists for them). Their dedication has had an influence on their home lives, as Meera’s family members make clear. It has also prompted hard choices, such as those faced by Suneeta, who is conflicted about remaining devoted to her professional commitments and living up to the traditional marriage obligations expected of her. But, given their obvious love of this work, it’s hard to imagine any of these journalists walking away from their vocation, especially given how far they’ve come.

Considering the success KL has achieved, it’s positioned to become a major news source in India at large, not just in Uttar Pradesh. Having risen from a local to a regional media outlet, KL is now poised to become a national player. It has even begun to be recognized outside of India, a reputation that’s likely to grow with the release of this film. That could prove to be especially important in light of the changing sociopolitical environment within India, a nation that’s seeing the rise of religious authoritarianism and the impact it’s having on the country’s secular life. With comparable movements taking place in other nations around the world, KL’s coverage of this phenomenon within its homeland could play an important role in keeping citizens elsewhere informed about this potentially significant (and growing) global development.

In the meantime, as this documentary illustrates, the Dalit women of KL can take a well-deserved bow for what they’ve accomplished. In an age when journalism has become increasingly suspect, unreliable and untrustworthy, it’s comforting to know that there are still committed media organizations out there devoted to reporting with honesty, integrity and a burning desire to uncover the truth. And it’s heartening to see that some of the most important work in this area is coming from unlikely sources such as this. KL has set an inspirational example for others to follow at a time when it’s truly needed.

In many ways, the women of KL embody qualities like persistence and fortitude, providing a noble and uplifting model for all of us to follow. And they reached that point through their own initiative – not just their actions, but also their attitudes and outlooks, the driving forces that have kept them going when others may have readily surrendered. This illustrates the power behind our beliefs, the foundation of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting our existence. Considering what they’ve achieved, those are some powerful beliefs at work.

To a great degree, the beliefs of the women of KL are rooted in the notion of faith, not of a religious nature, but of a firmly established conviction in themselves and what they’re capable of accomplishing. It’s a quality that permeates what they do, driving their efforts and the attributes that characterize them. Their commitment to objectivity and their ability to authentically follow through on that promise, for example, are apparent in how they cover the news, a hallmark of their signature reporting style. It’s a refreshing approach that has won over many devoted followers who have tired of the bald-faced editorializing that has come to typify much of mainstream journalism and to undermine its credibility.

The foregoing thus spotlights the inherent honesty and integrity these journalists bring to their work, another core belief behind their efforts. This is crucial to the realization of our manifestation ventures, given that such attributes are reflective of the true selves of those behind these efforts. Indeed, the more we tap into those qualities, the greater our chances of successfully fulfilling our intents, with results that faithfully emulate the qualities incorporated into them.

KL has employed a truly bold and courageous approach in carrying out this mission. Considering the conditions under which these journalists have had to operate, they have had to deal with limitations and dangers that could have easily stopped them in their tracks, but they refused to give up. They devised creative solutions and actively faced their fears, galvanizing them in their efforts to attain their goals. And, for their efforts, they have produced something viable and truly admirable.

The bottom line in this is that the staff of KL has committed itself to its goal. Even though the organization’s initial output is but a mere shadow of what it yields today, the growth of this media outlet’s coverage and audience reflects the effort that went into generating those results. The team’s belief in commitment is undeniably potent, and the magnitude of that attribute is apparent in what has resulted, a powerful creation that has left an indelible mark on the field of journalism and Indian society.

Directors Ghosh and Thomas have compiled an engaging, multifaceted, up-close look at this group of truth seekers in their documentary feature debut. In chronicling this story, the filmmakers often placed their own lives in jeopardy, frequently venturing into dangerous situations, conditions where the intrepid reporters’ work placed them in potentially grave peril. The result is a captivating watch in which viewers witness a compelling, no-holds-barred, boots-on-the-ground real-life story unfold, with no advance clue as to how things will ultimately turn out. Consequently, prospective audience members should be aware that some footage may be difficult for sensitive viewers. Also, viewers may experience some sound quality issues in streaming this release from some online sources (when I watched it, background sounds and the film’s score came through loud and clear, but the dialogue was problematic; thank goodness for subtitles). These considerations aside, however, “Writing with Fire” is exactly what its title says it is – a passionate, inspiring story about a group of truth seekers who have refused to give up at a time when it’s become all too easy for many of us to do so. Good for them – and, ultimately, for us.

This Academy Award nominee for best documentary feature has played at film festivals and in limited theatrical release and as part of the PBS documentary series Independent Lens. The picture has since been made available for streaming online on a variety of platforms.

Over time, David and Goliath stories like this have become a movie industry staple, both in narrative and documentary film genres. However, every so often, one comes along that truly stands out for its distinguishing attributes, and “Writing with Fire” is one such example. In an age where truth has regrettably become increasingly compromised, we need virtuous champions like the women of KL to carry on the tradition of accurate, reliable reporting, because, if we fail to support and preserve resources like this, we may all end up paying the price.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

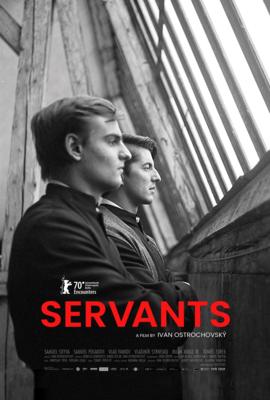

Reviews of "Everything Everywhere All at Once," "Cyrano" and "Servants" are all in the latest Movies with Meaning post on the web site of The Good Media Network, available by clicking here.

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” (2022). Cast: Michelle Yeoh, Jamie Lee Curtis, Stephanie Hsu, Ke Huy Quan, James Hong, Jenny Slate, Tallie Medel, Brian Le, Andy Le. Directors: Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (the “Daniels”). Screenplay: Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (the “Daniels”). Web site. Trailer.

How well do “you” (sometimes called “the localized you,” the version of ourselves with which the majority of us are most familiar) know the totality of your true self? Chances are most of us aren’t even aware of the existence of any of the other parts of ourselves, let alone any of the particulars about them. But those well versed in metaphysical circles have a good sense about our innate multidimensionality and what that can do for us (as well as those other parts of ourselves). Some of this might sound somewhat cryptic, but making audiences aware of this phenomenon is what the new manic comedy-drama “Everything Everywhere All at Once” is all about.

When Evelyn Wang (Michelle Yeoh), the beleaguered owner of a laundromat, is simultaneously beset by an array of issues, it seems, like the movie’s title implies, that everything is hitting her all at once. For starters, there’s her milquetoast husband, Waymond (Ke Huy Quan), whom she’s grown tired of and wants to divorce. Then there’s her lesbian daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu), whom Evelyn is torn about when it comes to dealing with her lifestyle and partner, Becky (Tallie Medel). Compounding all that is her father, Gong Gong (James Hong), an aging, high-maintenance senior, who recently arrived from China. And, as all of this is going on, she struggles to operate the business and plan a Chinese New Year party.

But, if all that weren’t enough, Evelyn and Waymond are also facing the scrutiny of an IRS audit, an investigation assigned to a hard-nosed, no-nonsense agent, Deirdre Beaubeirdra (Jamie Lee Curtis). Deirdre, it seems, has no life outside of her work, so she meticulously devotes all of her time, energy and effort to ruthlessly probing the details of the tax returns she’s assigned to review. She prides herself on the many awards she’s received for her scrupulously attentive work, and, as she performs her initial analysis of the Wangs’ return, she gleefully salivates over what she sees, already picturing herself nabbing another trophy.

As all of this is going on, however, events start taking some extremely strange turns. Beginning as early as the elevator ride up to the IRS office and continuing once inside, Evelyn begins having what seem to be visions, out-of-body experiences, and auditory and visual hallucinations. Given that they occur so suddenly and unexpectedly, she’s totally unprepared for them. Given that they involve concepts she’s never heard of before, she doesn’t know how to respond. And, given that the information associated with them appears to be delivered by someone who claims to be an otherly dimensional version of Waymond, she’s confused beyond belief. But one point that comes through loud, clear and repeatedly is the alternate Waymond’s contention that this version of Evelyn is the one he has been seeking for ages. And, in explaining what he means by this version of Evelyn, he raises the concept of “the multiverse,” the aggregate amalgamation of all the different universes that can potentially exist and in which all of us have an alternate self in existence.

So why does the alternate Waymond want this Evelyn? He says it’s because she possesses certain specialized talents that none of her counterparts have. And, as for the skills in question, the alternate Waymond says it’s her abilities for being able to effectively take on a growing evil that threatens the viability of the multiverse. He says it’s up to her to fix things or face the possible destruction of the multiverse. But, as for what those skills are, Evelyn doesn’t have a clue, especially since she has virtually no awareness or understanding of the multiverse in general, let alone how to repair it. So now what?

It’s at this point that the film launches into a grand adventure whose narrative is far too complicated to explain here. Suffice it to say, however, that the Evelyn viewers meet initially learns about the nature of the multiverse and what it can enable for each of us. This includes the ability to tap into parts of our “selves” that we previously knew nothing about, such as their skills, knowledge, attributes and talents, qualities that we can tap into and draw from in being able to resolve the issues we each face in our “home” universe. It’s an enlightening and educational experience, one that teaches us about ourselves, our “selves” and how the two can interact for the betterment of each other. It’s quite a wild ride indeed.

There are no doubt times when we’ve all thought ourselves to be more than what we’re immediately aware of. We may have only a vague notion of what that actually means, but we’re nevertheless aware that there’s something to that undefinable but undeniable quality. That fuzzy intuitive impression may seem like something that’s easily dismissed, yet it’s something we shouldn’t ignore. The reason? It provides us with an important clue to the true nature of our being.

Those who are well-versed in metaphysical studies understand that such impressions are intended to help us grasp the multifaceted, multidimensional nature of who we are. The “localized” version of ourselves is understandably the one with which we’re most familiar, but it’s only one part of something larger, a “being” that goes by various terms, such as “higher self,” “multidimensional self” or “oversoul.” The other individualized components of that greater self – often referred to as “counterparts” – reside in other dimensions or other “universes” in which they possess various attributes, some of which may be similar to ours, others of which may be remarkably different. In either case, we possess connections to those other selves, whether or not we’re aware of them. However, should we become cognizant of them, it’s possible to forge significant bonds with them, linkages that can prove to be beneficial to both them and us.

Those unfamiliar with these notions may well ask, how is all of this possible? As implausible as it all may sound to some, we can chalk it up to the philosophy of conscious creation, which maintains that we each manifest the reality we experience through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents. And, given that the range of these resources is inherently infinite, it makes possible an infinite range of materializations, each of which occupies its own corresponding dimension or universe, all of which, when taken collectively, constitute the multiverse, the concept to which Evelyn is introduced for the first time.

Like many of us, Evelyn initially looks upon the concept with skepticism. However, when she has an opportunity to experience those other dimensions and to interact with those other selves, she can see the qualities they each possess. Those attributes run the gamut of possibilities, from the ridiculous to the sublime to the inspiring. In one permutation, for example, Evelyn meets her other self from a universe in which everyone has hot dogs for fingers. In another, she sees herself as a seasoned kung fu master. And, in yet another still, she views Evelyn the glamorous and successful movie star.

At first glance, some may look upon this and heave a heavy “So what?” But, upon closer inspection, we might begin to see the value in this. When we consider the skills these other selves possess, we might also be able to understand how we can draw from them to benefit our localized selves. For instance, when alternate Waymond tells the local Evelyn that she has the skills necessary to take on the growing evil threatening the existence of the multiverse, she initially has no idea what he’s talking about. However, when she sees the other Evelyns, she begins to grasp how she can draw from their experiences to hone her abilities for taking on the task at hand. Her kung fu master self, for instance, shows her localized counterpart how to employ her previously dormant fighting skills when called upon. And so it goes with each of the alternate selves localized Evelyn meets, enabling her to amass a repertoire of abilities that will stand her in good stead for tackling her ultimate task.

Evelyn thus sets an inspiring example for the rest of us. She shows us how she’s able to become more than who she thought she was. She opens her mind to possibilities that she hadn’t previously considered. She tosses aside fears and limitations that have been holding her back. And she draws from these experiences to alter her beliefs and her reality in ways she had never envisioned. Through this process, the various problems that had been hitting her with everything from everywhere all at once suddenly don’t seem like the foreboding issues they once did. It’s as if she’s able to become her own superhero, capable of taking on whatever challenges she faces – and succeeding.

In light of the foregoing, multidimensionality probably doesn’t sound as far-fetched or ridiculous as it once may have. Instead, it can be viewed as the valuable tool it truly is. And, given that, it might not be so easily dismissed. All it takes is opening our minds to the possibilities and availing ourselves of them when they present themselves. Worth a try, wouldn’t you say?

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” is quite a film, in some ways a masterpiece and in others a project in need of work. This insightful and hilarious exploration of an array of heady philosophical, metaphysical and moral concepts is, in many respects, a visual assault on the senses but one that’s punctuated by stunningly clever visual effects, huge laughs, uproarious send-ups of a variety of other films, and dynamite performances by Michelle Yeoh and Jamie Lee Curtis. In many ways, it reminds me of the recent release “Strawberry Mansion” but on steroids. Unfortunately, however, that’s where the picture gets itself into trouble. In its attempt to cover a lot of ground, it gets bogged down by its own content, going on far too long and telling a story that could have easily been trimmed by about a half-hour. This could have been accomplished by eliminating some bits that overstay their welcome (such as its take-offs of martial arts movies, which start out funny but grow tiresome after a few too many run-throughs). It also would have worked better by focusing on its philosophical and metaphysical themes and deleting the moral concepts, which don’t work as well and only serve to slow down the overall pacing. This offering from directors Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (the “Daniels”) is certainly an ambitious and inventive release, but it’s unfortunate that the filmmakers didn’t know when to stop. It’s indeed worth a look, but it’s regrettable that the directors didn’t have the wherewithal to “kill their darlings” and quit while they were ahead. The film is currently playing theatrically.

It’s been said that there are times when we all exceed our expectations, becoming more than we thought we could be. Indeed, in these situations, we truly surpass the sum of our various parts. For instance, one need only look to the many examples of individuals who exhibit feats of superhuman strength during times of crisis. Where does that come from? It’s hard to say, but perhaps those individuals have alternate selves who dwell in dimensions where such capabilities are the norm and they’ve learned how to tap into those abilities and employ them in this reality. Whatever the source, however, what matters most is the ability to make the connection and put it to use when it truly counts. Evelyn seems to have learned how to do this – and maybe we can, too.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.