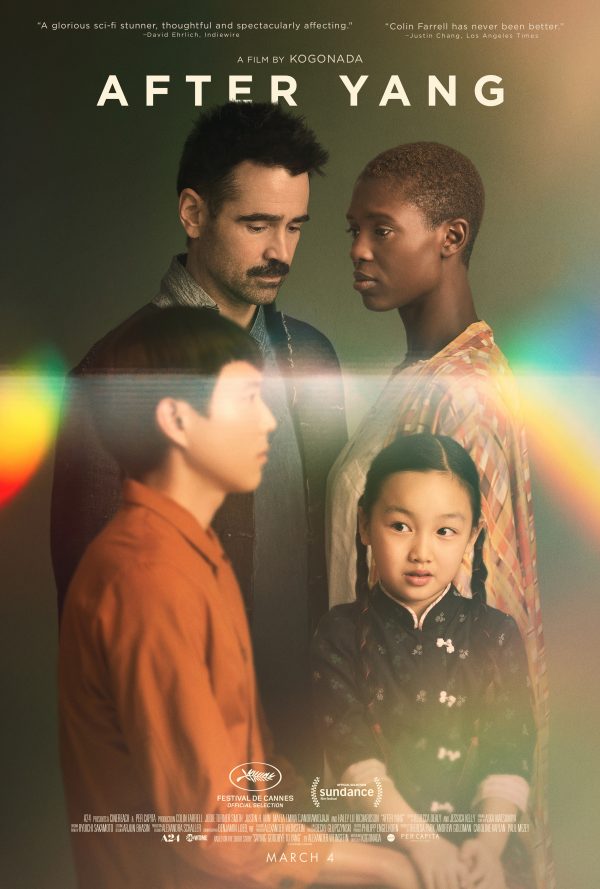

“After Yang” (2021 production, 2022 release). Cast: Colin Farrell, Jodie Turner-Smith, Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja, Justin H. Min, Haley Lu Richardson, Clifton Collins Jr., Ritchie Coster, Sarita Choudhury, Orlagh Cassidy, Ava DeMary, Adeline Kerns, Ansley Kerns. Director: Kogonada. Screenplay: Kogonada. Story: Alexander Weinstein, “Saying Goodbye to Yang” in Children of the New World. Web site. Trailer.

We all know what it takes to be human, right? In fact, as far as most of us are concerned, it’s a done deal, case closed, no further discussion. However, in an age of rapidly evolving technology, we’ve begun to realize that those hard and fast definitions have come up for reevaluation. A friend, for instance, has always been thought of as someone we interact with in person, not someone we communicate with halfway around the globe on the internet and have never met physically. But do these circumstances with such an electronic pen pal make this individual any less of a friend? Distinctions like this can carry profound implications, even more so than by this example, as seen in the thoughtful new cinematic meditation, “After Yang.”

What constitutes a family? That’s a question whose answer has been steadily evolving in recent decades. The traditional nuclear family, consisting of a pair of heterosexual parents and their offspring, generally of the same racial or ethnic background, has gradually been giving way to alternate configurations with increasing degrees of variation and acceptance. And it’s a trend that’s likely to continue on into the future as new developments begin to enter the picture. That’s particularly true in light of the evolution taking place in the nature of individuality. Indeed, given that families inherently consist of collections of individuals, the nature of those groupings will continue to change as the nature of those who make them up also continue to change. For example, as we move forward, will individuality continue to be based strictly on questions of biology alone, or will something else – like sentience – supplant or complement it? That being the case, then, what we think of as families and individuals may become something very different from what we’ve been traditionally accustomed to.

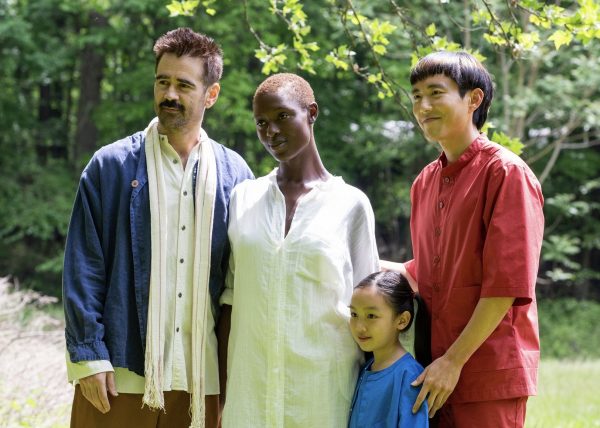

Such is the case in the Fleming household, a San Francisco family of the future. Parents Jake (Colin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith) live with their adopted daughter, Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja), a young Chinese girl. However, given that Mika’s Caucasian father and African-American mother come from vastly different backgrounds from her, Jake and Kyra are concerned that their daughter may not have enough of an opportunity to learn about her cultural heritage. Also, as an only child, they believe she could benefit greatly from the presence of an older sibling role model. But how can such a void be filled?

The answer is simple, thanks to a company called Brothers and Sisters Inc. The company has developed sophisticated trans-sapien technologies, enabling families to fill in the gaps in their households by making it possible to purchase synthetic beings (mostly children and siblings) who embody the qualities they’re looking for. In the Flemings’ case, for instance, Jake and Kyra approached the company to acquire an older brother for Mika, an Asian young adult who is programmed to be familiar with Chinese culture. These specifications are thus embodied in Yang (Justin H. Min), a synthetic who Jake and Kyra purchase to serve as a loving sibling and mentor for Mika. Yang cares deeply for his younger sister and readily shares an array of insights about life, as well as a wealth of “Chinese fun facts.”

As time passes, Mika comes to adore Yang and vice versa. Yang assimilates into the family so seamlessly that it’s hard to tell he’s not a strictly biological being. He truly blends into the household, and Mika is not the only one who looks upon him as a family member. Jake and Kyra genuinely come to view Yang as their son to the same degree that they view Mika as their daughter, even though both of them are not their own biological offspring. Together they make for a loving family unit. Indeed, who says that the nuclear model is the only one that’s truly “legitimate”?

All is well until one day when Yang inexplicably starts to malfunction, a development that starkly impacts the family household. Mika is especially upset, given how much she adores her older brother. And her parents, particularly Jake, are committed to find out what’s gone wrong. They’re determined to do whatever they can to see that Yang is properly repaired, especially since he’s still under warranty. But, as this process plays out, Jake and Kyra quickly find that this may be easier said than done. The warranty, it seems, doesn’t cover what appears to be ailing Yang, and fixing the problem may not be possible. In fact, it soon becomes apparent that recycling Yang for another trans-sapien unit may be the only realistic option.

Jake is far from satisfied with this solution. He sees Yang as more than a household appliance and, accordingly, is willing to explore alternative possibilities further. At the recommendation of the family’s neighbor, George (Clifton Collins Jr.), Jake takes Yang to a free-lance repairman, Russ (Ritchie Coster), who clandestinely fixes malfunctioning units like Yang – and not always legally.

After initially examining Yang, Russ also concludes that he may well be beyond repair. His investigation is more thorough than what was done at the warranty center, though the answer is essentially the same. However, Russ proposes one additional possibility that might offer a solution, even though it would involve performing an illegal procedure. Essentially the procedure calls for opening up Yang’s central processing mechanism, a practice that would violate the manufacturer’s protected proprietary technology rights. Jake is admittedly reluctant, but, if it offers potential hope for restoration, he’s willing to go along with it.

Despite the possibilities this procedure offers, as the repair process drags out, the family grows increasingly torn. Mika has become distraught over the fate of her brother. Kyra, meanwhile, has come to believe that it’s time to move on, that the stress of this situation has begun to place undue strain on the well-being of the household. And Jake, in his efforts to be a caring and protective father, has grown weary over everything that has gone on and what it has done to his family, especially Mika. He begins to wonder how much longer he can allow this to continue and what else he might do to reach a solution that’s in everyone’s best interests.

Upon completion of the covert procedure, Russ reveals that Yang indeed can’t be repaired. However, in the course of his work, he makes a startling discovery – he finds that Yang has been fitted with a sophisticated recording device, one that compiles a wealth of the unit’s memories. Russ speculates that this device is essentially a form of spyware that the manufacturer uses to collect a wealth of highly personal information about the unit’s owners for data mining purposes, information that’s subsequently harvested and sold at the time the unit is recycled. It’s quite a revelation, not to mention an egregious invasion of privacy.

But Jake’s interest in the recording device is different. He hopes it might provide clues as to what caused Yang to malfunction, so he decides to review the recordings with that aim in mind. And what he finds is eye-opening. He gains new insight into what Yang believed to be important in his life. More than that, though, he also develops a new appreciation for the impact that Yang had on him, Mika and Kyra, as well as a mystery woman (Haley Lu Richardson) whom Jake knew nothing about. But, most importantly, this exercise provides everyone – characters and viewers alike – with a new understanding of what it means to be “human,” regardless of whether one’s nature is based on biology or technology.

What is the family to do with this information? And what’s to become of Yang? What prompted the malfunction that led to his demise? And who is the mystery woman who showed up in his memories? That all remains to be seen as events play out in the wake of this domestic misfortune.

Given the power and persistence of our outlooks on the world, it’s easy for our views to become locked into place. That’s attributable to our beliefs, the building blocks of our existence, as made possible by the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting our reality. However, as experience shows us, despite such power and persistence, our beliefs can also be quite malleable, adaptable to new thoughts and ideas, particularly when evidence appears showing us that the notions we once thought were intractably unchangeable are indeed capable of adjustment and alteration. And, as this movie shows, that’s true for such basic life assumptions as what we believe constitutes the nature of family, individuality and humanity.

For instance, “After Yang” provides us with a blueprint for how it’s possible to see ourselves and those we love as being based on considerations other than mere biology, the belief basis we have typically used for ages. As the film shows us, it’s indeed conceivable for Jake, Kyra and Mika to have a deep, meaningful relationship with a synthetic. Yang’s sentience and emotions appear to be just as “real” as anything a flesh-and-blood biological is capable of, so is it any surprise that his family members would react the same way toward him that they do toward one another? If you doubt that, think of this another way: Jake and Kyra love Mika just as much as if she were their own biological offspring, yet, as their adopted daughter, clearly she’s not, but that difference doesn’t block the connection between them. So why should it be otherwise with Yang?

These changing definitions of what we believe constitutes family and individuality reflect our ability to overcome limitations in our perspectives. And that, in turn, illustrates for us how our beliefs are often based on arbitrary distinctions, choices that can be changed as long as we allow it. In fact, as conscious creation maintains, such shifts should actually be expected, since one of the philosophy’s core principles is the inherent evolution in the nature of existence, that everything is in a constant state of becoming. If this concept seems uncannily familiar, one need only look to the Buddhist precept of the impermanence of all things. Indeed, all things considered, at bottom, those notions don’t seem fundamentally different from one another. (Or, as a wise old sage once said, “You say tomAto, I say tomOto….”)

The more we look at this, the more we begin to realize, does it really matter from whence sentience arises? If the impact that another’s consciousness on us is as profound as is depicted in the Fleming household, is it really important where those feelings come from? This becomes apparent in the review of Yang’s memories, when we see his profound heartfelt interactions with Jake, Kyra, Mika and the mystery woman. As Jake, a tea vendor, discusses his fascination for the beverage and its potentially transcendental nature, we witness Yang’s sincere intent to share in this understanding. When Kyra admires Yang’s butterfly collection, they engage in a deep, meaningful philosophical discussion about the metaphorical metamorphosis that occurs when a caterpillar evolves into what it eventually becomes. In a stroll through a garden with Mika, Yang explains the age-old horticultural practice of grafting and how it symbolizes what happens in a family when “outsiders” are joined to the collective and how it makes the unit more richly diverse. These are insights and reactions one might not typically expect to come from an “artificial” life form.

Yang’s existence also draws attention to another belief worthy of being dispelled – that artificial intelligence is intrinsically – and always – harmful. Through a bevy of sci-fi stories, we have been routinely conditioned to believe that there’s absolutely nothing good that can possibly come out of such technology. But can one honestly say that the ways in which Yang interacts with his family members are innately evil? To be sure, one could make an argument in favor of that notion because of his internal recording device as a means of conducting invasive data mining, but it’s important to remember that this is a technology developed by man, not by the synthetic. Indeed, that naturally makes one wonder who the real villain is here.

By extension, the film also makes clear how important it is for us to incorporate elements in our existence that help to offset the impact of a high-tech world. The ubiquitous presence of technology in this future existence is routinely and deliberately counterbalanced with high-touch aspects – prolific and beautiful gardens, environments filled with serenity-inducing elements, and, of course, the presence of gentle, compassionate, empathetic artificial life forms. We need such influences in our lives (especially these days), and their essential importance is recognized in this society of tomorrow. Such elements can be introduced any time we want; all it takes is the will to do so and the supporting beliefs to make it happen.

The impact on biologicals like us can truly be significant, too. It urges a greater respect toward others and the world around us, including all of its elements, regardless of the fundamental foundations underlying their existence. It promotes wider acceptance and tolerance of others, including those who are different from us. In fact, it even prompts a heartfelt desire for honored remembrance, such as when Jake contemplates memorializing Yang’s life in a museum exhibit with the assistance of a compassionate curator (Sarita Choudhury). If that’s not a step forward for humanity, I don’t know what is.

It’s also impressive to see the lengths that Jake is willing to go to in order to save Yang. It’s more than just trying to effect repairs to a piece of broken-down technology. It’s a genuine effort to save a member of the family, to preserve the loving, collective nature of the household for its continued health and well-being. This kind of touching heroic effort is to be commended for what it seeks to achieve, illustrating a kind of compassion and appreciation that we could all stand to learn from. And to think that such a lesson in learning what really matters in life comes to the family – and us – from a machine. What a tremendous irony – and insight – that is.

How often does a movie seek to address the big questions of life? Well, if you’re the filmmaker Kogonada, the answer to that question would appear to be “every time.” Like his previous beautiful and ambitious release “Columbus” (2017), the director has successfully followed up that offering with this even more beautiful and ambitious project. Based on the short story “Saying Goodbye to Yang,” this thoughtful and emotive cinematic meditation raises intriguing questions about what it means to be human, largely through countless recollections that bring those considerations to the fore and give both characters and viewers pause to examine and reevaluate outlooks that may have once been rigid but can now be looked upon in a more fluid light. With fine performances all around, stupendously gorgeous cinematography (a Kogonada hallmark) and a lovely background score, “After Yang” evokes a profound array of moods, from joyful to sad to reflective, leaving one supremely touched by the experience, and it’s all accomplished without violence, evildoers or malevolence. There are occasional pacing issues, and a few of the ideas raised are left less than resolved (most likely intentionally), but overall this is a truly stirring experience, one whose impact will linger long after the lights come up. The picture is playing theatrically and online.

When all is said and done in our lives, do the tangible qualities of those who have impacted us the most really matter in the end? Perhaps that might be true in certain contexts, like sexuality, but, when it comes to the things that really matter most – the intangible emotional bonds we forge with such individuals, for example – does it really matter if they’re biological, technological or even physically present in our lives? When framed in that way, we have an entirely new perspective to draw from, even though the bottom line influence and connection may be the same in either case. Indeed, it’s the bond that ultimately really matters most, and that, it would seem, is what truly counts when it comes to our assessments of what it means to be human. Yang shows us this here. Maybe we should listen.

Copyright © 2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment