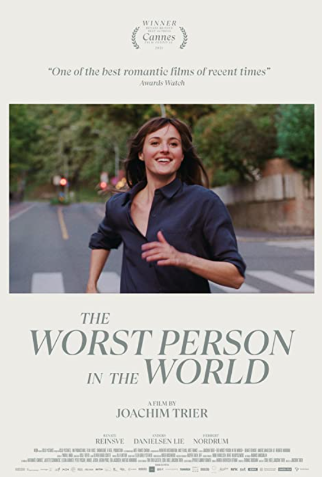

“The Worst Person in the World” (“Verdens verste menneske”) (2021). Cast: Renate Reinsve, Anders Danielsen Lie, Herbert Nordrum, Maria Grazia Di Meo, Hans Olav Brenner, Vidar Sandem, Marianne Krogh. Director: Joachim Trier. Screenplay: Joachim Trier and Eskil Vogt. Web site. Trailer.

Passing judgment is something that, for what it’s worth, seems to come all too easily to most of us. That’s especially true when someone engages in acts that affect us negatively, and, in some cases, such blame may be genuinely deserved. But what happens if such effects result from acts that originate with honest, benign intentions? And what if we unwittingly contribute to those outcomes? How should we react then? Is judgment still warranted? Such are the questions raised in the new Norwegian rom-com/character study, “The Worst Person in the World” (“Verdens verste menneske”).

Making up one’s mind about what one wants out of life isn’t always easy. That seems to be especially true for Julie (Renate Reinsve), a twenty-something Oslo resident who seems perpetually lost in a sea of indecision. Consider her career path, for example. Having attained good grades as an undergraduate, she’s thrilled to have qualified to enroll in medical school. But, not long after starting down this path, she finds herself bored and dissatisfied, prompting her to change lanes and pursue the study of psychology. Of course, that doesn’t work out, either, and so she picks up a camera to try her hand at photography, a pursuit that she believes will leave her more creatively fulfilled. It also introduces her to an array of interesting people, most notably sexy, eligible men. And, with this development, her romantic life quickly turns robust and virtually takes over, essentially rendering her once-vibrant career ambitions secondary.

One evening, while on a date with one of her edgy hipster beaus, Julie’s life takes yet another turn. She meets Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), a successful graphic novelist known for his politically incorrect material. They hit it off well, despite their age difference (Aksel is a decade older). They soon move in together, Julie seeming to have finally shed her ostensibly fickle ways. Indeed, she may have finally found what she’s looking for.

If only that were true.

Julie’s restlessness with her circumstances soon resurfaces. She’s still unsettled vocationally, trying her hand at writing and then taking a job working in a bookstore, but nothing feels quite right. Each time something doesn’t work, she unhesitatingly backs away, often quite suddenly and seemingly spontaneously, all the while making her discontent plainly known. What’s more, tensions slowly simmer in her relationship with Aksel, who, with the onset of middle age, is looking to finally settle down and start a family, a goal that Julie doesn’t share. She hasn’t closed herself off from the idea of having children, but she’s clearly not interested in it for the foreseeable future. So what’s next?

That’s a question Julie is unprepared to answer. She has a good handle on knowing what she doesn’t want, but her grasp of what she does want is virtually nonexistent. Her resolute, unapologetic indecisiveness comes to be viewed as capricious, even somewhat narcissistic, especially when she freely acknowledges and acts on it, even if there’s significant fallout that impacts others. At the same time, though, she’s also quietly troubled by her lack of progress in finding herself, an outgrowth of that same indecisiveness, a point made all the more apparent as her 30th birthday approaches – and as Aksel’s star continues to rise.

This quandary bubbles to the surface when she attends a publishing event with Aksel, where his successes are widely celebrated and she is largely relegated to the background. Discouraged, she decides to leave, telling Aksel that he should stay and enjoy himself. After departing, Julie chooses to walk home, taking a leisurely stroll through the streets of Oslo. While on her way, she walks past a residence where a lively wedding reception is taking place. She’s curious about the festivities and the fun that everyone seems to be having, prompting her to spontaneously crash the event.

Despite Julie’s best efforts to inconspicuously blend in, however, her cover is not convincing enough to fool one of the guests, Eivind (Herbert Nordrum), a married café barista who’s attending the event solo. They strike up a lengthy conversation on a variety of subjects, a dialogue that’s decidedly intimate but without turning overtly sexual. They opt not to take matters to that level, because Julie’s not prepared to cheat on Aksel, and Eivind can’t bring himself to be unfaithful to his wife, Sunniva (Maria Grazia Di Meo). Nevertheless, there’s a definite chemistry between them, most likely driven by their comparable ages and outlooks on life. By evening’s end, they part ways, believing their chance encounter to have been a pleasant, one-time event.

Again, if only that were true.

As time passes, relations sour between Julie and Aksel and between Eivind and Sunniva, freeing them up to pursue new possibilities. Julie and Eivind complement one another well in that, unlike their former partners, they’re each willing to give the other space and freedom to be themselves, unwilling to bend to the others’ whims. It’s an arrangement that seems destined for success. But there comes a time when that thoughtful, accommodating understanding begins to slowly deteriorate. The freedom this relationship affords Julie shines a bright light on the fact that she still hasn’t found herself or her destiny, leaving her once again feeling unsettled and unfulfilled, especially when she sees Eivind content to stay put and enjoy the laid-back stability that his relationship with Sunniva often didn’t allow, something the restless one looks upon as unambitious.

Julie’s quiet obsession with this failing gnaws away at her, leaving her feeling like “the worst person in the world.” It’s an emotion that has dogged her for quite some time, too, especially when it’s been exacerbated by the judgment leveled against her by others, most notably those who have been negatively impacted by her unapologetic self-directed behavior over the years. In some ways, they also view her as the worst person in the world for having inflicted such inconsiderate anguish upon them, even though her actions, regardless of how hurtful they may have been, were nevertheless open, honest, up-front responses to the unsatisfactory circumstances that she decided she was no longer willing to endure. Ironically, some of Julie’s actions came in response to what others sought to impose upon her, conditions that she ultimately saw as limiting and unacceptable. In a sense, then, those behaviors could conceivably be viewed as making each of those other individuals out to be the worst person in the world in their own right, too. Indeed, perhaps this is a quality that we all potentially carry within us, thus raising questions about how we should respond when it comes to judging the behavior of others – particularly when we might well possess the same trait we’re criticizing. (Something about being without sin and casting the first stone comes to mind here.)

This realization thus places Julie in an entirely new light. To be sure, some of her behavior could justifiably be seen as inconsiderate and selfish. Yet, in light of the foregoing, what some might see as unacceptable, self-centered behavior may just be part of being human, a characteristic we may all possess to a certain extent. Consequently, undergoing such situations could be looked upon as a difficult but integral aspect of learning what it’s like to be who we inherently are, no matter how much we might dislike it. Pointing fingers in dismay at transgressors might provide a degree of short-term relief under such conditions, but it doesn’t dismiss the fact that scenarios like this also constitute an opportunity to hold up a mirror and take a good, hard look at ourselves – and learn that we may need to go easier on others in circumstances like these. Indeed, going Biblical once again, let us forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.

So where does Julie go from here? That’s what ensues as the remainder of this story unfolds, and there are even more unexpected twists and turns that occur along the way, some of which don’t directly originate with her. Such events thus provide Julie with an opportunity to hold up a mirror to herself and see the impact that the actions of others can have on someone – and, this time, on Julie herself.

Finding oneself can be challenging when we don’t have a clue, and Julie’s experience is far from exceptional. However, one aspect helps to distinguish her circumstances from those that many go through – she’s not afraid to admit it. As she tries her hand at multiple endeavors, she has the courage to recognize what doesn’t work. She’s genuinely lost, which accounts for her ongoing changes in vocation and romance. And the more such changes occur, the more she becomes convinced that’s her nature, a notion that becomes embedded in her beliefs and, consequently, in the reality around her. Such is the output of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the existence we experience based on our thoughts, beliefs and intents.

Many would probably legitimately wonder why Julie can’t make up her mind. Others – especially those more intimately familiar with her – would also look upon her in anger and disappointment given the negative impact her behavior often has on them. They’re likely to claim that she led them on, and, on some level, one could argue that they’d be justified in their feelings. At the same time, though, Julie is generally up front about herself. Even if she’s indecisive, she’s at least authentic about it, and, while that may be frustrating for others to deal with, it’s nevertheless honest, a crucial starting point in helping her figure out what she wants. That, of course, depends on not becoming so entrenched in beliefs about her indecisiveness that she becomes perpetually stuck by it.

To Julie’s credit, her willingness to explore various aspects of life can ultimately work to her benefit. By leaving herself open to investigating different possibilities, she increases her chances of finding what best suits her, enabling her to rule out what doesn’t work and to include what does. Indeed, as conscious creators well know, everything in our existence is in a constant state of becoming, an expression of the inherent evolution that we all go through, and the more we allow it, the more likely we’ll arrive at what we’re looking for.

This can prove to be a valuable life lesson. Oftentimes, though, we don’t allow ourselves to experience it. We’re frequently afraid that others will frown upon us for making frequent changes, seeing us as fickle or flighty. In turn, we may subsequently heap shame upon ourselves for that, viewing our inability to choose as a fault rather than as a means to legitimately find our way. And, should that happen, we really run the risk of becoming stuck – permanently.

This is where the foregoing discussion about judgment becomes so important, especially if our behavior contributes to the indecisiveness that someone experiences. Undue criticism on our part toward them may lead to the stagnation and a lack of focus they undergo, prompting them to unwittingly accept the labels that are unjustly thrust them. And, all the while, we may not acknowledge the part we played in the development of the beliefs and actions that caused these results. Indeed, we may inadvertently contribute to the making of what we later unfairly criticize.

No matter how we end up getting to where we’re supposed to be, we should learn to be gentle on ourselves – and others – as we make our way there. It’s a process, one often filled with trial and error as we move forward. This is not meant to be an out for inexcusable behavior, but it is intended to be forgiving when the need genuinely arises. That may be a challenging belief to embrace, but we just might find that it’s one that pays valuable dividends in the long run, both for us and those who benefit from it – and for anyone else who has a little bit of the worst person in the world in them.

Writer-director Joachim Trier’s latest illustrates how the journey of self-discovery is not an easy one, a process about which we should be careful in terms of how we judge it, especially when we realize that the bottom line in this is something to which we might all fall prey, mainly because we’re all ultimately only human. Told in 12 chapters, a prologue and an epilogue, the film provides a series of snapshots of this process rather than an ongoing sequential narrative, showing viewers how events play out for the protagonist over time as she seeks to find herself. The sparklingly crisp screenplay, penned by the director and collaborator Eskil Vogt, features insightful writing reminiscent of Woody Allen, particularly in its spot-on depiction of women’s sensibilities. The picture’s expertly blended palette of diverse filming styles and superb lead performance of Renate Reinsve (winner of the best actress award at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival) combine with all of this offering’s other strengths to make for one the year’s best movie-going experiences. While the film has primarily played on the festival circuit thus far, it’s scheduled to go into general release on February 4. Avid cinephiles should rush to go see it.

Even though “Worst Person” has largely flown beneath the radar thus far, it has not gone without recognition. As noted above, Reinsve captured the best actress award at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, an event at which this release also earned a nomination for the Palme d’Or, the festival’s highest honor. In addition, the picture captured a Critics Choice Award nomination for best foreign language film. It has also been shortlisted as Norway’s official entry in the International Feature Film category at this year’s upcoming Oscars.

Who we end up becoming depends on what we believe and how we see ourselves. It would be great if such visions popped into our heads with sparkling definition and clarity, but, as Julie’s experience illustrates, that’s not always the case. Consequently, as we sort out those images and that process, we need to cultivate patience and tolerance with ourselves – and those around us – as we undertake such a venture, one that requires committed determination and may even result in some pleasant surprises. But few things will quash that enthusiasm faster than undue criticism and misplaced judgment. They can derail the process and leave us forever lost, and that truly might leave us feeling like the worst person in the world.

Copyright © 2021-2022, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment