The Chicago International Film Festival recently completed its 2021 edition in its first-ever hybrid format with theatrical, virtual and drive-in screening options. This flexible approach made it possible for viewers to screen a variety of films in the traditional manner, from the comfort of their own homes or stretched out in their cars. While some of the presentations were available in Illinois only, both theatrically and virtually, many others could be streamed nationwide, making it possible for movie fans to see some excellent films without being in the Windy City, an increasingly popular viewing option for many film festivals (and one that I heartily applaud).

Thanks to this new format, I was able to screen a great number of films – 22 in all. The festival’s 57th edition had its share of fine offerings, but there were also a number of pictures that could have been better. Below are my summary reviews of the releases I watched. Full reviews of select films are to come, where noted.

“Amira” (Egypt/Jordan/UAE/Saudi Arabia) (5/5)

What makes us who we are – our personal character or our immutable DNA? That’s the central question raised in this domestic drama with a sociopolitical twist. When Amira (Tara Abboud), a 17-year-old Palestinian girl conceived with the smuggled semen of her imprisoned father (Ali Suliman) (an opposition political leader confined by the Israelis), discovers that the man she has always thought of as her dad is not her biological parent, the revelation creates chaos within her immediate and extended family, as well as among his unincarcerated political allies (Waleed Zuaiter, Ziad Bakri). This becomes most apparent in her search to uncover her true lineage, a process hampered by her uncooperative mother (Saba Mubarak), who thwarts Amira’s efforts at every turn. Writer-director Mohamed Diab’s latest has been unfairly labeled a soap opera and a manipulative melodrama, but these flimsy criticisms ignore the profound impact of this clandestine practice, one that has been playing out for nearly a decade and has implications extending beyond immediate family units. While it’s true that the somewhat overlong final act is at times a bit overdramatic and occasionally unduly dogmatic, the filmmaker’s sincerity in attempting to portray circumstances that go beyond mere private domestic matters is indeed commendable. All of this is made possible by the fine performances of Abboud, Suliman and Mubarak as the once-happy family members whose lives are suddenly and unexpectedly thrown into turmoil. Pay no attention to the cynical critics about this one; it’s a fine, engaging effort well worth the viewing time. Full review to come.

“Madeleine Collins” (France/Belgium/Switzerland) (5/5)

Sustaining suspense and keeping viewers guessing for nearly two hours is quite a feat, but writer-director Antoine Barraud successfully manages to do just that in his latest release, a seamless blend of two genres – psychological thriller and romantic drama. With a number of homages to Hitchcock, as well as many mind-bending tricks of his own, Barraud’s tale of a woman (Virginie Efira) leading two lives – one in Paris and one in Switzerland – dangles an array of intriguing clues before his audience and always manages to confound even the most astute viewers with a parade of new revelations in seemingly every scene. However, despite the narrative’s many misdirections, the story never becomes so confusing or convoluted that it can’t be followed. Instead, the film breeds a succession of delicious “a ha!” moments, maintaining interest as the story slides into a satisfying home stretch. Credit Efira for shouldering the load here, delivering a riveting performance and making it look effortless. Indeed, if this movie were a book, it would be a real page-turner from start to finish. Don’t miss this one.

“The Worst Person in the World” (“Verdens verste menneske”) (Norway/France/Sweden/Denmark) (5/5)

When we don’t know what we want out of life, we may appear to others as fickle, capricious or self-centered, especially if we’re not afraid to admit to such uncertainty. And that, needless to say, doesn’t always bode well for our reputation with others. But is this kind of self-acknowledged indecisiveness truly a character failing, perhaps even a symptom of unacknowledged narcissism? That’s what the protagonist (Renate Reinsve) of this insightful, superbly written Norwegian comedy/drama/character study is up against, a scenario in which the film’s principal could easily be characterized as the embodiment of the picture’s title. However, as this offering also shows, it’s possible to say that there just might be a little of the worst person in the world in all of us, an observation that should give us pause to consider how we not only see others but also ourselves. Writer-director Joachim Trier’s latest thus illustrates how the journey of self-discovery is not an easy one, a process that we should be careful to judge, especially when we realize that the bottom line in this is something to which we might all fall prey, mainly because we’re all ultimately only human. The sparklingly crisp screenplay, expertly blended palette of filming styles and stunning lead performance of Reinsve (winner of the best actress award at this year’s Cannes Film Festival) combine to make a thoroughly enjoyable and thoughtful movie-going experience not to be missed. This definitely deserves a general release, and, should that happen, avid cinephiles should rush and go see it. Handily my favorite film of the festival. Silver Hugo Award winner, Best Cinematography. Full review to come.

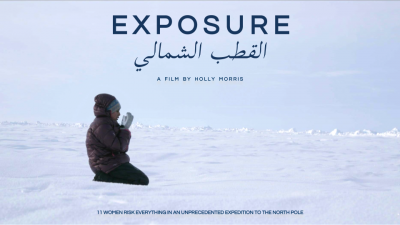

“Exposure” (USA/Iceland/Oman/Saudi Arabia) (4/5)

Reaching the top of the world is far from an easy task, even under the best of conditions. But, in an era of climate change, in which the warming of the planet is causing the ice that must be traversed to reach the North Pole, that undertaking has become eminently more perilous. Director Holly Morris’s excellent, up-close documentary chronicles the 2018 adventures of an all-female expedition crew, detailing the challenges and dangers involved in such an inherently risky venture. This project, aimed at helping to draw attention to environmental issues and the possibilities afforded by women’s empowerment initiatives, is a historic one also in that it could well be the last of its kind due to the increasing dangers posed by such journeys. The film’s stunning cinematography and its highly personal treatment of the crew members’ individual stories makes this an intriguing and compelling watch about one of the planet’s last-remaining – and potentially fastest-disappearing – frontiers.

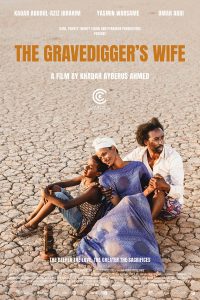

“The Gravedigger’s Wife” (“Guled and Nasra”) (France/Somalia/Germany/Finland/Qatar) (4/5)

What lengths would you go to for the one you love? That’s the core question in this multinational production about a Djibouti gravedigger (Omar Abdi) who barely ekes out a living and is now faced with coming up with the money to pay for a life-saving operation for his dying wife (Yasmin Warsame). This heartrending and heartbreaking tale has its predictable moments and a few story threads that aren’t as fully developed as they could have been, but the superb chemistry between the protagonists, enlivened by the excellent performances of Abdi and Warsame, make this an engaging and compelling watch overall. Writer-director Khadar Ahmed’s debut feature is a fine showcase for a superb emerging talent, one who shows tremendous promise for future projects. Full review to come.

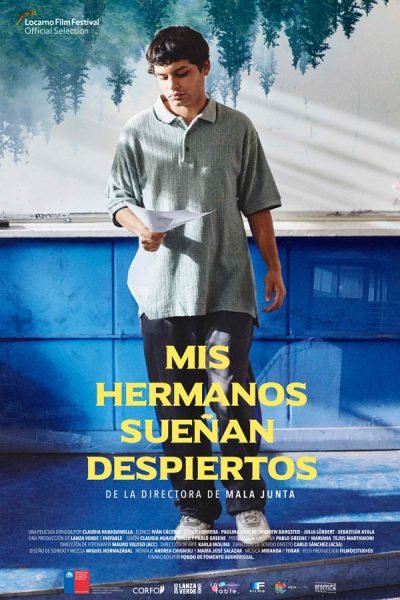

“My Brothers Dream Awake” (“Mis hermanos sueñan despiertos”) (Chile) (4/5)

When two teenage brothers (Claudio Arredondo, Sebastián Ayala) are confined in a Chilean provincial juvenile detention center, they dream of life outside their prison walls, although they have no idea when they’ll have the opportunity to experience it. Despite being charged with only petty offenses, they have no legal guardian to claim them, their mother having abandoned them upon lockup. With the days passing, the tedium growing ever-more exasperating and the stress mounting (particularly for the younger, more sensitive sibling), the brothers become progressively more frustrated – and desperate – to find a way to rejoin the world of the living. So, when an opportunity opens up to make that happen with their cell mates, they avail themselves of the chance, despite the risky nature of the plan. Based on conditions that once existed at one such facility, as well director Claudia Huaiquimilla’s experience working with at-risk youth, this sensitive, affecting drama puts viewers into the shoes of these troubled young men and women, many of whom didn’t catch any breaks before incarceration let alone once in confinement. Because the film touches on so many different aspects of juvenile detention life, it occasionally suffers from bouts of meandering and underdevelopment. But this is made up for by a fine ensemble cast, beautiful cinematography and a riveting concluding sequence that will leave viewers glued to their seats. The filmmaker’s sophomore effort isn’t always an easy watch, but it nevertheless makes a powerful and profound statement that bears heeding, no matter where one calls home.

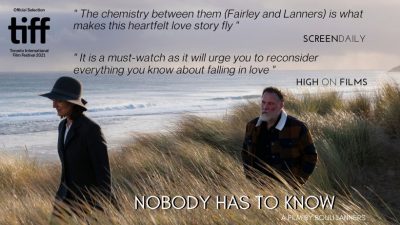

“Nobody Has to Know” (France/Belgium/UK) (4/5)

What if you were to lose your memory and then have an apparent stranger come up to you and say that the two of you were once lovers? Would you believe it? And what would you do? That’s the challenge for a stroke survivor (Bouli Lanners) who learns that his caregiver (Michelle Fairley) was once supposedly a love interest. It’s not as if he’s opposed to the idea of picking up where they supposedly left off, but he nevertheless remembers nothing of his involvement with her. Thus begins the start of an unusual relationship that he clearly enjoys despite the seemingly omnipresent nervousness she appears to exude. Is everything above board here? Or is something else going on, and how will that bode for their future? Writer-actor-director Lanners has concocted quite an engaging story in this film, successfully brought to life by his fine performance and that of co-star Fairley, both of whom captured CIFF Silver Hugo Awards for their portrayals. Admittedly, a few story elements don’t integrate into the overall narrative as well as they could have, but the picture’s gorgeous cinematography provides an excellent distraction to these modest drawbacks. As one of the most unusual love stories I have ever seen, this offering generally lives up to its potential and gives the heartstrings a good tug in the process. Silver Hugo Award winner, Best Actor (Bouli Lanners); Silver Hugo Award winner, Best Actress (Michelle Fairley).

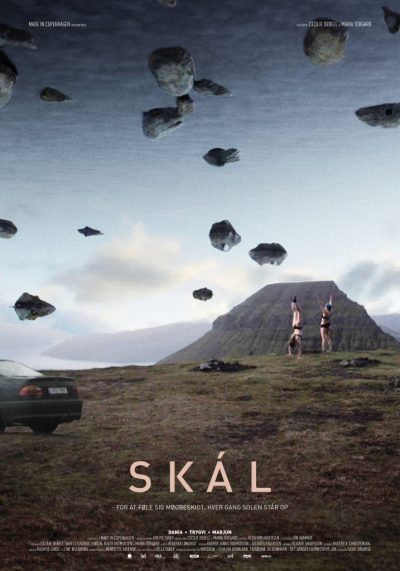

“Skál” (“Cheers”) (Faroe Islands/Denmark) (4/5)

Though billed as a documentary, this captivating release plays more like a docu-drama or even a big screen version of reality TV. The film tells a modern-day Romeo and Juliet story of sorts about Dania, a young, idea-filled poet from a conservative Christian community who falls for an outspoken, outlandish rap artist, Trygvi, whose shock-provoking lyrics are the antithesis of the values his long-sheltered girlfriend was raised with. Despite their differences and the pressure inflicted upon them through less-than-subtle parental misgivings, the couple steadily grows ever closer, especially as Dania becomes more comfortable in poetically expressing her conflicted feelings about genuine faith and the pitfalls of needlessly restrictive religious conventions. Directors Cecilie Debell and Maria Tórgarð thus present an honest love story with deep spiritual implications, narrative elements often lacking in similar offerings. The film’s truly breathtaking cinematography is a sight to behold, showing off the beauty of the Faroe Islands in ways seldom seen, combined with heartfelt, intimate depictions of personal moments, making for an unusual blend seldom seen in many movies, let alone those in the documentary genre. My only problem with this release is that so many of the most significant moments seem so perfectly captured that it almost makes me wonder about the validity of their authenticity, that they play more like scripted material than spontaneously caught events. That aside, though, this thoughtful, insightful release provides viewers with much to ponder, backed by gorgeous images and presented through a bevy of touching moments. What more could audiences ask for? Gold Hugo Award winner, International Documentary Competition. Full review to come.

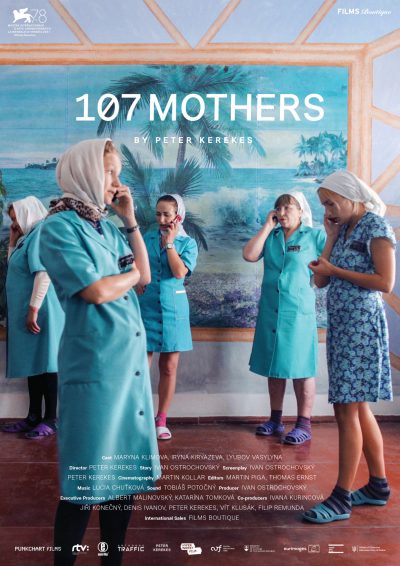

“107 Mothers” (“Cenzorka”) (Slovakia/Czech Republic/Ukraine) (3/5)

Raising a child as a single parent can be challenging enough in itself, but imagine trying to do so as a mother in prison. The harsh, regimented, bureaucratic conditions of this environment are challenging for all concerned – mothers, children, and even the staff of guards and professional caregivers, some of whom long to be parents but aren’t as “fortunate” as the inmates they oversee. Of course, one also needs to remember that these women are here for a reason, many of whom have been convicted of crimes as heinous as brutally murdering their unfaithful husbands and boyfriends. Such are the circumstances faced by a group of women incarcerated in a Ukrainian detention facility in this fact-based drama about what it’s like to undergo imprisonment while raising young ones. The inmates are forced to deal with considerations as daunting as the reality of their sentences, the guilt and psychological impact of their crimes (despite being the perpetrators themselves), and enduring separation from their children, something they could face permanently if they cannot find guardians to care for their little ones once they reach a certain age. Director Péter Kerekes’s third narrative feature is to be commended for taking on such a sensitive subject, its efforts at addressing an array of issues associated with such circumstances and doing so with an often-experimental approach. However, the film attempts to cover so much ground that it occasionally becomes somewhat unfocused (particularly in the first half), leaving viewers to wonder exactly where the picture is headed. To its credit, though, there are also some powerfully moving sequences that drive home the true pain associated with these conditions, situations that can’t help but evoke genuine empathy, even among the least sympathetic of viewers. A noble effort with much potential, even if it isn’t always fully realized. Silver Hugo Award winner, Best Director (Péter Kerekes).

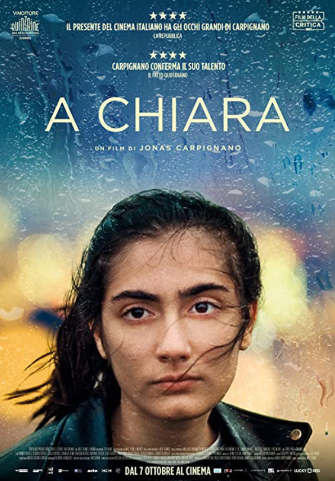

“A Chiara” (Italy/France) (3/5)

Finding out your family isn’t what you thought it was can be a personally devastating blow, especially for an impressionable adolescent. So it is for 15-year-old Chiara (Swamy Rotolo), who has long innocently believed that her home life is a bona fide 24/7 Kodak moment. But, when she witnesses a shocking incident and begins learning startling secrets about her Italian mob member father (Claudio Rotolo), she indignantly demands answers, most notably from her apparently better-informed relatives (Grecia Rotolo, Carmela Fumo, Antonio Rotolo Uno). However, none of her kindreds will respond to her questions, particularly when dad goes missing as a fugitive. How will she resolve these issues to her satisfaction? That’s what writer-director Jonas Carpignano examines in his latest feature film, a crime saga mixed with domestic drama elements told from the perspective of an insatiably inquisitive teenager. As unique as the narrative may be, though, this offering could definitely benefit from better editing (especially in the first half-hour), more plausible plot elements (particularly in the concluding act) and a more compelling coda to replace an ending that currently fizzles more than it dazzles. This could have been a fine release with some retooling, but, in its present form, it needs more salt.

“Captain Volkonogov Escaped” (“Kapitan Volonogov bezhal”) (Russia/France/Estonia) (3/5)

What does it take to attain forgiveness? That’s what a secret police operative (Yuriy Borisov) in pre-World War II Leningrad seeks when he realizes he’s been unwittingly involved in a program of rounding up and executing innocent civilians whom officials believe are possible threats based merely on their occupations, friendships, relatives and ethnicities. That revelation prompts him to take flight, especially when higher-ups begin to suspect that he’s no longer trustworthy. While on the run, his hope for redemption surfaces when he experiences a visitation from a deceased former associate who informs the agent that he’ll be damned to hell – just like all of his other late colleagues – unless he’s able to repent his transgressions and obtain forgiveness from at least one of his victims’ relatives. Armed with that information, the officer sets off on a quest to find someone who will forgive him, all while being hunted down by authorities who now consider the renegade agent a threat in his own right. In telling the captain’s story, directors Aleksey Chupov and Natasha Merkulova present a thoughtful Russian fable/morality play, one that mixes hard-edged reality with surrealism, metaphor and a surprising degree of spirituality in an era of godless Communism. It’s an intriguing, thought-provoking premise embedded in a game of cat and mouse, one whose elements sometimes come across as insightful and enlightening with others that seem surprisingly simplistic, almost naïve. Nevertheless, these shortcomings are compensated for by the intense lead performance of Borisov, the film’s superb cinematography and its brilliant dystopian production design. While not everything works in this unusual, genre-fusing offering, there’s enough to like here to make for an engaging, ponderous and mesmerizing time at the movies. Silver Hugo Award winner, Best Art Direction.

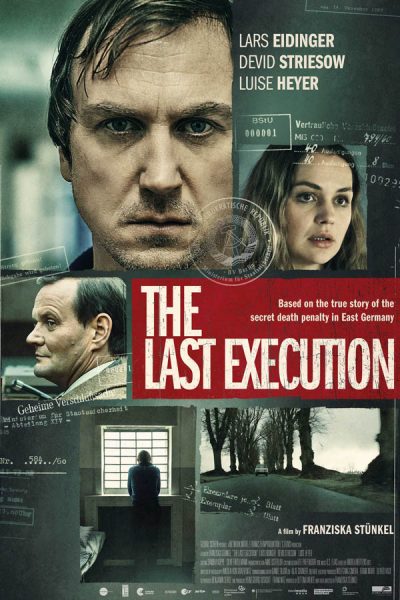

“The Last Execution” (“Nahschuss”) (Germany) (3/5)

Inspired by the life of Werner Teske, the last person executed in East Germany before the death penalty was abolished, this fictionalized account of his story follows the tragic experience of an ambitious but idealistic and naïve scientist/professor (Lars Eidinger) who sacrifices his integrity for the prospect of upward mobility when recruited to work for the Ministry for State Security (Stasi). Having landed a position of enviable comfort by East German standards, the devoted recruit initially complies with what’s asked of him. However, when he’s coerced into activities that he finds personally troubling, he has difficulty following orders, putting him under mounting pressure and enhanced scrutiny as he’s soon railroaded by his own agency. While director Franziska Stünkel’s second narrative feature starts off well as a finely crafted espionage thriller, it begins running out of steam as it switches tracks to explore the psychological aspects of its story, becoming increasingly plodding and riddled with extraneous sequences that could have easily been cut. It’s unfortunate that the intensity with which the film begins isn’t sustained when the protagonist wrestles with his crisis of conscience, a narrative development that one would think would have had the same sizzle potential as what preceded it. There are also plot elements that occasionally stretch credibility, particularly when it comes to the protagonist’s naïvete. As it stands, viewers are left with a film that works well some – but regrettably not all – of the time.

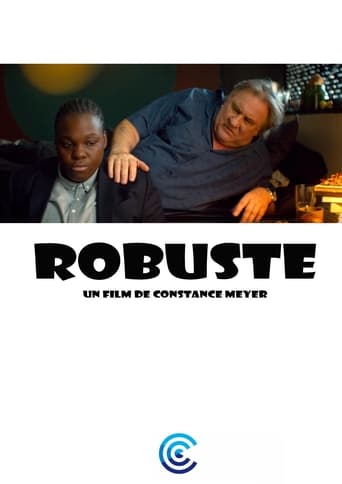

“Robust” (“Robuste”) (France) (3/5)

Web site

When an aging, eccentric, cantankerous actor (Gérard Depardieu) with health issues and a host of insecurities loses his body guard to several weeks’ personal leave, he’s flummoxed by the arrival of his replacement – a young female amateur wrestler (Déborah Lukumuena) who doubles as his protector. Much to his surprise, however, he quickly forms a strong friendship with his new security agent/personal assistant, one that proves mutually beneficial as he helps to bolster her career as she helps to get his career back on track. While the narrative is somewhat predictable at times, there are ample curve balls thrown our way, too, making for a generally delightful movie experience. This gentle comedy’s greatest strengths, though, are the fine performances by Depardieu and Lukumuena, as well as the strong, credible chemistry between the unlikely duo. While some story threads aren’t developed or resolved as well as they might have been, director Constance Meyer’s debut feature is nevertheless an impressive start to what one would hope is a flourishing career.

“Silent Land” (“Cicha ziemia”) (Poland/Italy/Czech Republic) (3/5)

Web site, Trailer

When an accident at an Italian rental villa results in the death of a maintenance worker (Ibrahim Keshk), the incident sets off an array of moral and relationship dilemmas for the wealthy Polish couple (Dobromir Dymecki, Agnieszka Zulewski) renting the estate for what becomes a tension-filled holiday. While the accident itself raises questions related to accountability, the film slowly and simultaneously also reveals that issues of personal responsibility extend further than just what happened on the property. This is apparent most notably in terms of what’s going on in the disintegrating relationship of the protagonists, issues that also parallel those of a local couple (Jean-Marc Barr, Alma Jodorowsky) whom they befriend. In relating this story, director Aga Woszczyńska’s debut feature subtly draws comparisons between the underlying meaning of the accident and the circumstances in the protagonists’ relationship, particularly when it comes to the responsibility we all carry with us with regard to what we contribute to the unfolding of such matters. However, while the film effectively builds suspense initially as it moves toward this central revelation, it eventually reaches a point where the narrative starts to meander in too many different directions, some of which could have been easily eliminated. Also, one can’t help but observe that, as the filmmaker’s intent comes into focus, it feels somewhat contrived – clever and insightful yet a little too deliberately planned for its own good. The result is an ultimately less-than-satisfying outcome, one that doesn’t quite match the intensely slow sizzle this drama/character study started with. Director Woszczyńska shows some promise with this first outing, but it’s clear she could stand to learn from a few more film projects as she moves toward living up to her potential.

“Wandering Heart” (“Errante corazón”) (Argentina/Brazil/Spain/Chile/Netherlands) (3/5)

Abandonment is a difficult issue whether one is on the receiving end or doing the deserting. Such is the experience of a middle-aged gay man (Leonardo Sbaraglia) who has been on both ends of this burning candle. It seems like he’s either leaving the ones he cares about or those whom he adores are leaving him, and it’s beginning to take an emotional toll on him. The same is true to an extent for those around him, most notably his daughter (Miranda de la Serna), a recent high school graduate, and his ex-wife (Eva Llorach), an entertainer who has trouble keeping centered. In each case, the characters are wrestling with their restless wandering hearts. But is that wandering being driven by an inability to commit or by fear, particularly the anxiety associated with being alone? Those are the questions the characters must deal with if they ever hope to hold on to their sanity, let alone be happy. In an age when feelings of isolation are becoming more prevalent, those are certainly important considerations to address. However, writer-director Leonardo Brzezicki’s handling of this issue leaves much to be desired. The characters’ behavior (most notably that of the protagonist) often lacks believability, presented as exercises in immaturity that truly stretch credibility. Then there’s a noticeable lack of specificity in the back story; its vague explanations never feel complete or satisfactory. And then there are the performances, which bring new meaning to the term “drama queen” on more than a few occasions. Finally, the forced feel-good attitude that emerges in the final act seems wholly out of place in light of what precedes it, cheapening the overall narrative. Still, to the film’s credit, it does take on a subject that’s seldom dealt with in movies, and there’s something to be said for that; it’s just a shame it wasn’t better handled.

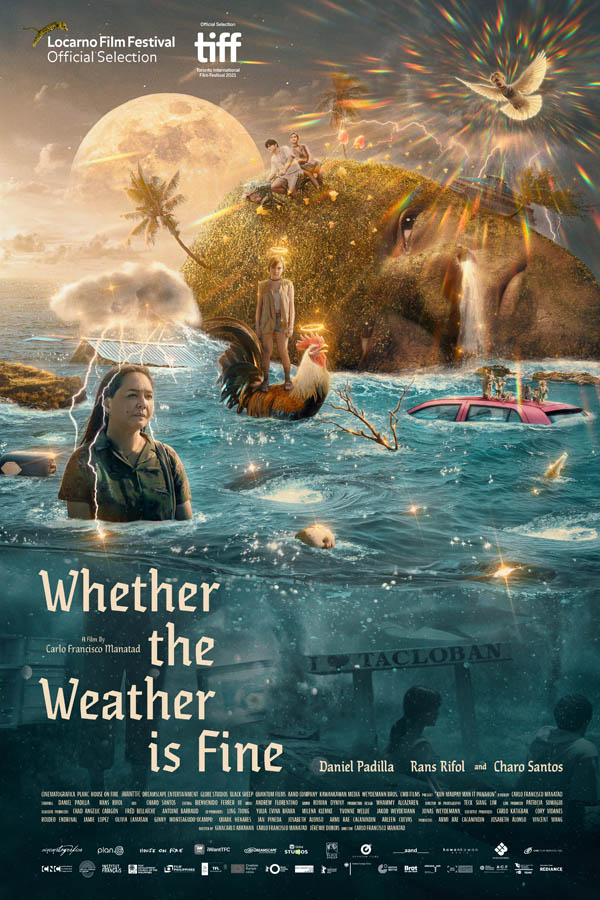

“Whether the Weather Is Fine” (“Kun Maupay Man It Parahon”) (Philippines/France/Singapore/Indonesia/Germany/Qatar) (3/5)

In a landscape strewn with debris, dead bodies, unattended farm animals and packs of out-of-control children, three survivors (Daniel Padilla, Rans Rifol, Charo Santos-Concio) of 2013’s Philippine Typhoon Haiyan wander what’s left of the streets of the City of Tacloban. Unsure about what to do, where to go and what the future may hold, they look for ways to survive. At the same time, though, they also wonder how something as horrific as this could happen, especially in a nation where devout faith in Christianity permeates the culture. In their wanderings, they find individuals devastated by their circumstances. But they also discover those who firmly believe that the strength of their faith will somehow miraculously sustain them, including through the acts and deeds of selfless Samaritans, some of whom seem unlikely candidates for such altruistic behavior. The result is a ponderous journey with elements that fuse gritty realism with wondrous surrealism. Director Carlo Francisco Manatad’s debut narrative feature is to be commended for its inventive perspective on such a troubling subject, one that’s characterized by scenes depicting such images as children gleefully playing in the shadows of unburied corpses. But the upshot of this is that it is possible to have hope in the face of despair, especially when miracles indeed happen. Admittedly the film could use some judicious editing at times, and there are some elements (such as the surprisingly upbeat score) that seem strangely out of place. However, the underlying message here is one that should not be summarily dismissed. After all, without hope, under trying conditions, what else have we got?

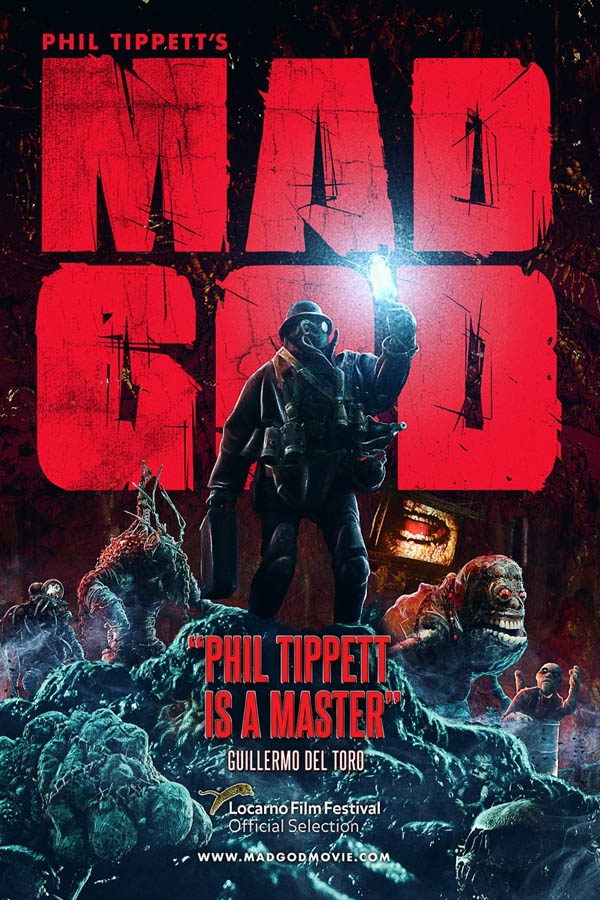

“Mad God” (USA) (2/5)

Ah, vanity. How lucky one is to have attained such notoriety for one’s work that one can then devote all one’s energies to a pet project that’s not necessarily meant to make money or win critical praise but to merely satisfy one’s own creative urges – especially those that are so far removed from the standards of conventionality that one couldn’t care less. That could be one way of summing up the essence of this stop-motion animation offering from director/special effects master Phil Tippett, best known for his work on films like “Jurassic Park,” “The Empire Strikes Back,” “Starship Troopers,” “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” and the original “RoboCop” series. This wildly imaginative, superbly produced, sometimes-funny, supremely decadent dark fantasy easily boasts some of the best and most elaborate stop-motion animation sequences ever created, even if they are also some of the most gratuitously and grotesquely disturbing ones ever made. While the imagery may be a feast for the eyes (though I wouldn’t recommend eating a meal while screening it), the nonlinear nature of the narrative grows progressively more tiresome the further one gets into it. Consequently, my rating here is indeed a generous one, primarily in recognition of the picture’s tremendous technical accomplishments, which were 30+ years in the making. However, although this work may succeed as a cinematic art piece with more than a few allusions to “God as mad scientist,” there’s little else to recommend in terms of what it has to offer as a motion (or, in this case, stop-motion) picture. But, then, when satisfying one’s own vanity is the main objective, as on a project like this, I suppose that’s all that really matters in the end, even if no one else shares in that vision – or enjoyment.

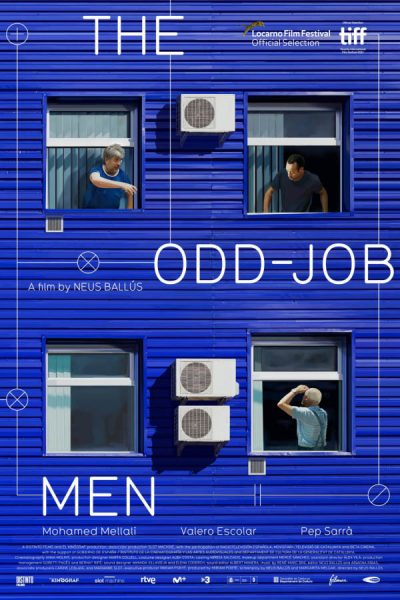

“The Odd-Job Men” (“Sis dies corrents”) (Spain) (2/5)

Though billed as a comedy, one would be hard-pressed to think so given the finished product. Despite a well-crafted production design and a simple but potentially engaging premise of this Spanish offering – that of a week in the transitioning lives of three handymen (Pep Sarrà, Valero Escolar, Mohamed Mellali) who work for a small maintenance and repair company in suburban Barcelona – the film never gels into what it could have been, resulting in a largely uninteresting, insubstantial snooze where viewers are left waiting for punchlines that never materialize. It’s not that the characters aren’t well drawn; they’re just not given much to do, and almost none of it generates the laughs one expects from its billing. Director Neus Ballús’s latest plays like the first draft of a script in need of serious shoring up (most notably some heavy dustings of laughing powder), despite originating in what could have been a rich vein of worthy material if suitably developed. Instead, viewers are left with a picture where it feels like the filmmaker could have done so much more with it but didn’t.

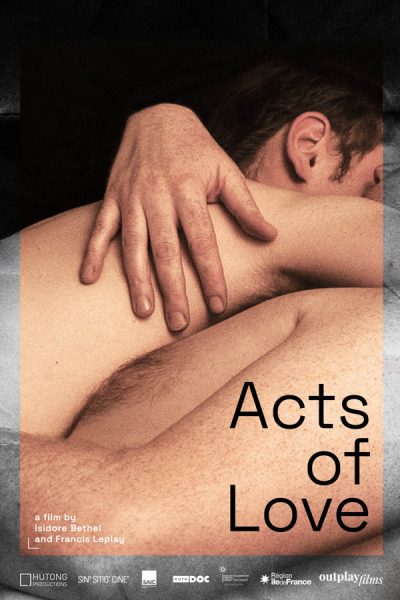

“Acts of Love” (USA/France) (1/5)

When director Isidore Bethel’s relationship with an older man sours, he takes a break from things and relocates from Mexico City to Chicago to make a film that, from the very beginning of the production, has no apparent sense of direction. It’s a trait more than amply apparent in the finished product, too. And, as revealed in recorded phone conversations during the course of the picture, the filmmaker’s mother absolutely hates it (and astutely so). This meandering stream of consciousness “documentary” consists mostly of director interviews and encounters with people off the street regarding matters of sex, love, intimacy and relationships, backed by musings of cluelessness and ennui, all linked by Mike Mills-styled bridge sequences. In the end, however, the picture essentially ends up being little more than a vehicle for potential hook-ups involving the filmmaker. There’s plenty of masturbation going on here, too, both of the intellectual kind and otherwise. Sadly, this is yet another example of pretentious, unfocused material erroneously being passed off as alleged high art. Thankfully, Mom sees through it all and doesn’t hesitate to call out her self-absorbed son, absolutely nailing things when it comes to assessing exactly what’s wrong with this feeble excuse for a film. Indeed, as once again becomes apparent, “Mom truly knows best.”

“Come Here” (“Jai Jumlong”) (Thailand) (1/5)

I’m all for cinematic experimentation in the movies. But I draw the line at productions that play like self-indulgent film school projects made by students who assemble montages of their friends engaged in mundane pursuits that they then try to pass off as sublime art. So it is with director Anocha Suwichakompong’s third narrative feature about a group of stage actors vacationing in western Thailand. When they’re not sightseeing or rehearsing scenes for a play, they engage in utterly inconsequential conversations and pose for protracted (and I do mean protracted) silent close-ups. These segments are intercut with images of bookstores, people sleeping, hydroelectric plants, trains and archive footage of a now-closed zoo. But all of this is to what end? Some say it’s a dream. Others contend it’s a visual tone poem. For me, it’s one giant WTF, but, frankly, your guess here would be as good as mine. While the film is admittedly beautifully filmed in black and white, it moves by at a snail’s pace, the kind of picture that makes one long for a fast forward button. In fact, one could probably get up to use the restroom and come back 20 minutes later having not missed anything. I implore you not to waste your time on this one, because it’s an hour and ten minutes you’ll never get back.

“Friends and Strangers” (Australia) (1/5)

Web site, Trailer

I’ll come right to the point about this one – it sucks, and in more ways than I can count. Writer-director James Vaughan’s debut feature may bill itself as a comedy, but there is absolutely, positively, unquestionably nothing funny about it, other than perhaps being an utterly laughable joke in itself. This cinematic mess has been called a wry, witty, understated look at the ennui of lost, self-conscious millennials comically searching to find their way in contemporary Australian culture and society. I call it self-indulgent, incomprehensible B.S., a collection of uncorrelated film clips strung together trying to pass themselves off, individually and collectively, as something ironic and allegedly profound. I laughed only once during the film’s 84-minute runtime, which, because nothing essentially happens, seems far, far longer than what the clock might say. It’s sad that the Australian movie industry, which has long been known for producing many great films, has to suffer a blemish like this on its reputation. It truly deserves better treatment than that.

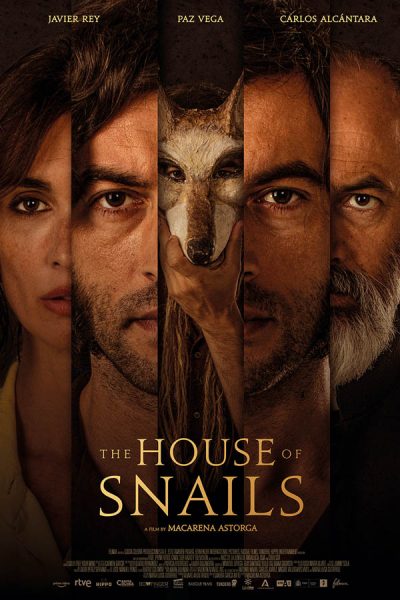

“The House of Snails” (“La casa del caracol”) (Spain/Peru/Mexico) (1/5)

Take a pinch from every horror movie genre you’ve ever seen, order them in an incoherent sequence and add a big reveal that’s not too difficult to spot from a distance (despite attempts at throwing in misdirections or red herrings), and you’re left with this predictable, underwhelming, occasionally gratuitous Spanish entry in a genre that’s all too often characterized by these trite shortcomings to begin with. Besides the foregoing issues, the film also suffers from hammy overacting, formulaic timing for the introduction of clichéd revelations, and, of course, the requisite blatantly bad decision-making typical of most horror films. And then there’s the title, which has precious little to do with what actually unfolds on screen and in many ways feels like an afterthought thrown in to keep viewers guessing at its relevance (which, by the way, is largely unsatisfying to boot). Director Macarena Astorga’s debut feature shows she truly has her work cut out for her as a filmmaker. In fact, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that even devoted fans of this genre would probably walk away disappointed from this one.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment