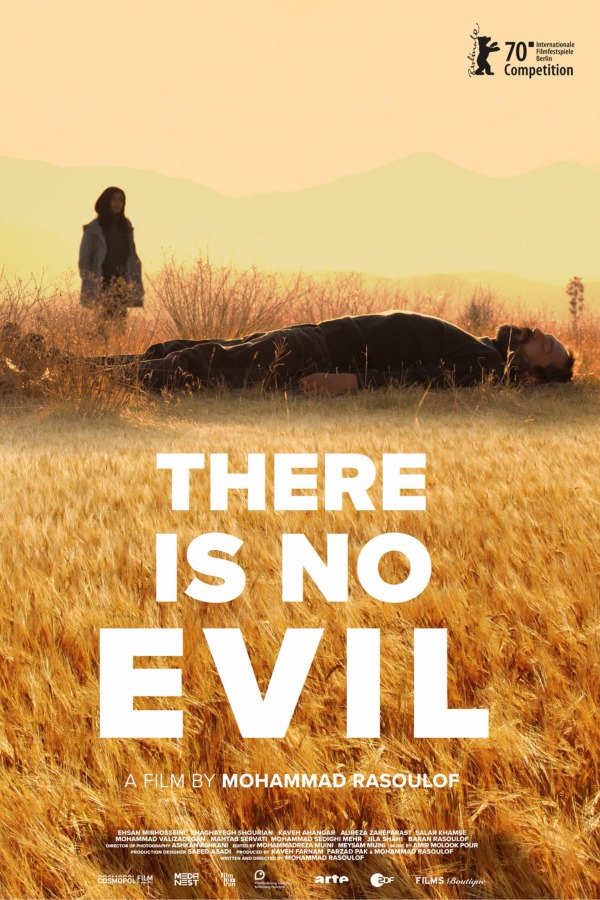

“There Is No Evil” (“Sheytan vojud nadarad”)(2020). Cast: Ehsan Mirhosseini, Shaghayegh Shoorian, Kaveh Ahangar, Darya Moghbeli, Alireza Zareparast, Salah Khamseh, Pouya Mehri, Mohammad Valizadegan, Mahtab Servati, Baran Rasoulof, Mohammad Seddighimehr, Shahi Jila. Director: Mohammad Rasoulof. Screenplay: Mohammad Rasoulof. Web site. Trailer.

Listening to our conscience often proves challenging. In many instances, we know in our heart of hearts what we should and shouldn’t take part in. But saying no isn’t always easy, especially if our necks are on the line if we refuse to play along. Indeed, it can be difficult to stick to our guns when we have one pointed at our head. At the same time, though, dismissing our convictions can carry consequences far more onerous than those that come with failing to comply with the dictates thrust upon us. Those thorny questions provide the basis for the controversial but revealing new Iranian drama, “There Is No Evil” (“Sheytan vojud nadarad”).

“Remorse,” “regret” and “defiance” are words most of us would not readily associate with executioners, but they’re more than apropos when it comes to the characters in director Mohammad Rasoulof’s latest. This collection of four vignettes about the lives of executioners – many of them ordinary citizens who have been conscripted into the military and involuntarily forced into situations bigger than themselves – examines how these individuals cope with their circumstances, revealing feelings that those in this grim profession generally aren’t believed to possess. Taken together, these segments paint a picture quite different from the cold, unfeeling personas that most of us probably assign them without a second thought. This is not to suggest that they should be exonerated for what they do (even though the responsibility for killing the “guilty” is often imposed on them), but it is a reminder to the rest of us that situations like this are often far more complicated than how we typically characterize them.

In the film’s opening sequence, which carries the same title as the picture itself, viewers are introduced to Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini), who comes across as a middle class, middle-aged everyman. He lives with his wife, Razieh (Shaghayegh Shoorian), and their young daughter, and they spend their days on the sort of routine tasks that most families do – running errands, paying bills, visiting relatives and doing housework. Heshmat seems like a thoughtful, gentle soul in many ways, going out of his way to help people with things like freeing a pet cat trapped under equipment in his apartment building’s parking garage. And he seems generally agreeable, willing to do what others ask of him and even going out of his way to look for ways to spoil his daughter.

But there’s another side to Heshmat that seems a bit off. Much of the time he appears quietly preoccupied, almost withdrawn, staring off into space and even zoning out occasionally, a potentially precarious hazard at times, such as when he’s stopped at traffic signals and fails to notice the lights change. He’s also on medication of some kind, one that Razieh sometimes has to remind him to take.

So what’s Heshmat’s story? For much of this segment, viewers seem to be watching little more than an average Joe going about his ordinary, everyday routine. Even when he finally goes to his job, his workplace looks rather nondescript, an innocuous, Spartan control room in which he makes himself coffee and perfunctorily carries out several administrative functions. But it’s also here where audiences learn what he does for a living, a chilling revelation that suddenly sheds new light on much of what came before. That’s particularly true when it comes to his removed demeanor and need for prescription drugs. If any of us were to do what he does for a living, we’d probably find ourselves in the same boat.

In the film’s second sequence, titled “She Said, ‘You Can Do It,’” we meet Pouya (Kaveh Ahangar), who has just begun his mandatory two-year military service. He’s anxious to get it over with and receive an honorable discharge so that he can apply for a passport that will enable him to move overseas and live with his girlfriend. Pouya’s a gentle, sensitive sort, far different from the grizzled, hard-edged band of roughnecks (Darya Moghbeli, Alireza Zareparast, Salah Khamseh, Pouya Mehri) he bunks with in his barracks. This difference becomes acutely apparent when, during a troubled bout of insomnia, he expresses his reservations about having to carry out one of his first orders – executing a prisoner.

Given Pouya’s sensibilities, he’s convinced he can’t bring himself to kill someone. He discusses his hesitancy with the others, all of whom offer different suggestions about how to handle the situation. But all of the proposed solutions come up short in one way or another, and Pouya is still left with his dilemma.

But is all lost? Well, that depends on what happens when another option emerges. It seems that the old adage “When there’s a will, there’s a way” has more viability than we might have thought, especially when it comes to removing ourselves from activities we believe to be inherently wrong. The meaning of “You Can Do It” thus takes on new meaning – and unexpectedly so.

The film’s third segment, “Birthday,” takes matters in a decidedly different though tragically bittersweet direction. Javad (Mohammad Valizadegan), a young military man, has been given a three-day pass to pay a surprise visit to his girlfriend, Nana (Mahtab Servati). It’s her birthday, and a big celebration is planned. And, to top off the festivities, Javad plans to give her what he hopes will be the best present she receives – an engagement ring.

However, much to Javad’s disappointment, he learns upon arrival that the festivities have been cancelled. That’s because Nana and her family have just received word that a close, longtime friend has died. The birthday party that had been in the works is now in the process of being transformed into a memorial service.

Nana is particularly sad, given that she was close to the deceased family friend. Javad tries to offer comfort, though he holds back somewhat, because he has questions about the nature of the relationship that existed between Nana and the “friend” about whom he previously knew nothing. Circumstances grow increasingly tense, especially when more information about the friend’s death by execution surfaces. And, as the details of that killing come to light, it starts to strike a nerve that makes the situation ever more uncomfortable.

How will matters play out? And what will it mean for the future? The birthday is already anything but happy, but will that sadness linger on afterward? Indeed, the pain of execution can carry consequences that extend outward far from those most immediately affected, as this scenario so painfully depicts.

The film’s concluding sequence, “Kiss Me,” tells the story of Darya (Baran Rasoulof), a young Iranian expat raised in Germany. Even though she has spent much of her life in Europe, she still has relatives in the family homeland whom she has never met. To make up for that, Darya’s father arranges for her to visit her Uncle Bahram (Mohammad Seddighimehr) and Aunt Zaman (Shahi Jila), who live in the remote Iranian countryside, where they raise honeybees and Bahram informally serves as the community’s de facto physician.

As someone who is preparing to become a doctor, Darya is curious about her uncle’s folk medicine practices. But she grows concerned when she sees that Bahram could use some healing himself, the kind that goes beyond what his brand of home care can provide – and that he refuses to get. This disconnect, along with other issues, such as Darya’s unwillingness to go hunting with Bahram (“I refuse to kill a living thing,” she boldly proclaims), set off tension between niece and uncle. That condition worsens when Bahram and Zaman continually and perplexingly refuse to engage with the ways of the modern world. Darya begins to suspect that they are hiding something from her and announces her intention to return to Germany if they don’t come clean. She soon sets that process in motion, but it isn’t complete until revelations finally emerge that confirm her suspicions – and in more ways than she imagined.

Although these four stories are vastly different from one another, they all ultimately deal with the notion of reluctant executioners and the dilemmas they face in connection with their work (if one could even legitimately call it that). The expressions of this concept ultimately take myriad forms, yet they all circle back to the same underlying notion. And they manifest as they do because the beliefs underlying them – all originating from the same common roots – are what drive the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon the power of these resources in materializing the reality we experience.

The beliefs in question here, of course, are those dealing with matters of conscience. In particular, the story explores how individuals who are uncomfortable with, or who outright object to, such extreme acts respond to them when ordered to carry them out. Indeed, the regime that mandates such actions may have no problem with them, but those charged with their fulfillment clearly do, even if the specific ways they react differ from individual to individual. And their emotional reactions, in turn, affect how they respond to what they’ve been ordered to do.

Heshmat, for example, responds by withdrawing, distancing himself from his actions by manifesting various escape mechanisms. Pouya, by contrast, looks for options to extricate himself from what he’s been mandated to do, a seemingly impossible undertaking but one that he pursues with the same fervor that fuels his disapproval of executions. No matter what course the executioners may follow, though, their efforts at dealing with their circumstances all originate with the beliefs that manifest their particular responses. And, even if they’ve never heard of conscious creation, it’s apparent that its principles guide them in their intents and subsequent actions.

In most of these cases, their reactions are driven by a strong sense of responsibility, particularly when it comes to the consequences that arise from their actions. They cringe at what results (or could result) from those actions, prompting them to ask themselves, “Do I really want that weighing on my conscience?” and “Can I live with myself if I do what I’m told?” They obviously possess a strong sense of personal integrity and place tremendous value on their beliefs associated with it. They’re not content to toe the line and fall back on an excuse as flimsy as “I was just following orders.”

Yet, in attempting to escape such circumstances, they face great peril, with far-reaching repercussions that could potentially lead to their own executions for failure to comply. So, to get past such conditions, they must forge beliefs and use manifestation skills that enable them to overcome their fears and the limitations that stand in their way. That’s no easy feat considering what they’re up against, but that’s where the importance of creativity and the power of their beliefs comes into play.

This is evident not only in the actions of the principals in the film, but it also played a key role in how the picture itself was made. Director Rasoulof, a longtime outspoken critic of the Iranian government, has faced various restrictions on practicing his craft over the years, including a year’s imprisonment. But, despite such hindrances, he has felt compelled to find ways to keep working and spreading his messages. For instance, he has endeavored to make sure his pictures get seen, even if they’re banned from being screened within Iran itself. He has also made adjustments to his filming procedures, primarily working on scenes having indoor settings and assigning location and outdoor shots to assistant directors. And, in the case of “There Is No Evil,” he managed to circumvent some of the restrictions placed on him by essentially making the production a collection of four short films instead of a single narrative feature, something upon which Iranian authorities focus more of their attention.

That kind of passion for the power of creativity pervades this film, not only in terms of how it was made, but also among the solutions the characters devise for dealing with their circumstances. The responses in each case may not be “perfect,” but they illustrate a desire and effort to push boundaries, to break through the barriers that would otherwise prevent the characters from achieving their accomplishments and, by extension, from keeping their film’s message from getting out. That’s a truly inspiring example for those who dare to question the status quo, no matter how much dominance and control those who manage it may appear to wield. Indeed, when there’s a will, there’s a way.

While the film admittedly suffers from some occasional pacing issues and a slight tendency for the filmmaker to wear his heart on his sleeve, these minor drawbacks are easily overlooked in the wake of the picture’s many other strengths, particularly the power of its core message. Rasoulof is a master at delivering a punch when it’s called for, especially when it’s not seen coming. The stunning impact such gestures leave on us is often considerable, not unlike the lingering scare that often overwhelms us after we’ve escaped some kind of terrible accident when the realization of what could have happened finally sinks in. This is an impressive, important and meaningful offering that needs to be seen. The picture has primarily been playing the film festival circuit thus far, but a theatrical and streaming release program is in the works for later in 2021.

Capital punishment is a controversial subject worldwide, especially when the intents underlying it are questionable and driven by political agendas rather than legitimate, established guilt. Opinions on its merits and criticisms vary from country to country and from individual to individual. And the same would appear to be true even with those responsible for carrying out the deed. That naturally begs the question, “Why would someone opposed to the practice engage in such acts?” This film sheds some new light on that, revealing that answers to the question may not be as simple as assumed. What’s most important, though, is that, no matter how we might feel about it, we should strive to be authentic with ourselves, listening to our conscience and abiding by our sense of integrity. Should we fail at that, we could be saddled with quite a burden – one that might dog us for the rest of our lives.

Copyright © 2020-2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment