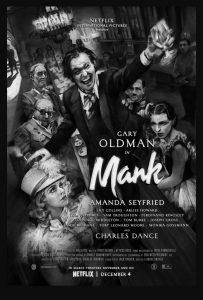

“Mank” (2020). Cast: Gary Oldman, Amanda Seyfried, Arliss Howard, Charles Dance, Lily Collins, Tom Pelphrey, Ferdinand Kingsley, Tuppence Middleton, Joseph Cross, Monika Gossmann, Sam Troughton, Tom Burke, Jamie McShane, Bill Nye, Jeff Harms, Paul Fox. Director: David Fincher. Screenplay: Jack Fincher. Web site. Trailer.

Speaking our truth is indeed a noble pursuit. Our faithfulness to our own authenticity is a clear indicator of our integrity, a quality widely respected by others and of which we should be personally proud. But not everyone appreciates such candor, especially if it ruffles the feathers of those who stand to lose much from such revelations. So it was for the writer of a big screen classic as depicted in the new Hollywood back story saga, “Mank.”

In 1941, writer-actor-director Orson Welles (Tom Burke) released the cinematic classic “Citizen Kane,” widely regarded as one of the greatest (if not the greatest) films ever made. The prodigious wunderkind, who began work on the picture in 1939 at the age of 24, had been given carte blanche by the film’s studio, RKO Pictures, to make the movie in virtually any way he saw fit, including the hiring of collaborators and controlling the final cut. It was an unprecedented contract and one that angered many moguls in the traditional Hollywood studio system.

Welles, who had established himself as an icon in the New York theater community and on radio, prided himself on the quality of his work, and he now sought to do the same in the world of film. That began with the script, and, to that end, he wanted the best screenwriter he could find, an assignment for which he tapped the services of Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman).

Mank had developed quite a reputation for himself in writing circles. Over the years he had worked as a correspondent for The Chicago Tribune, a drama critic for The New York Times and a contributor for The New Yorker. He later established himself as a prolific screenwriter in Hollywood, contributing to many scripts and frequently reworking the screenplays of other writers, often uncredited, as was the case, for example, with “The Wizard of Oz” (1939). He became known for his signature style, particularly his incisive wit and biting satire, making his work (especially his humor) some of the most distinguishable in the business, even if not officially acknowledged as such.

[caption id="attachment_11945" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman, left) prepares to pen the crowning achievement of his career, the screenplay for “Citizen Kane,” as chronicled in director David Fincher’s latest offering, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

Screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman, left) prepares to pen the crowning achievement of his career, the screenplay for “Citizen Kane,” as chronicled in director David Fincher’s latest offering, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

When Welles decided that Mank was who he wanted, he approached him with the offer. At the time, Mankiewicz was recovering from injuries suffered in a car accident. By virtue of being laid up, he was seen as being free to devote all his time to his writing, a condition it was hoped would keep him from being distracted by his chronic vices of compulsive gambling and incessant drinking. (Welles even sought to ensure that for the remainder of Mank’s recovery, albeit with only modest success, by setting him up to do his writing in a home on a “dry” ranch in Victorville, CA.) And so, with the assistance of a transcriber, Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), a housekeeper and physical therapist, Fräulein Frida (Monika Gossmann), and Welles’s liaison, actor-director-producer John Houseman (Sam Troughton), Mank began his work.

“Citizen Kane,” a thinly veiled fictional account of the life of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), was a controversial project from the outset. Given the clout wielded by the powerful businessman and former politician, Hearst was seen by many as an untouchable target whom no one would dare take on. But Welles, and especially Mankiewicz, weren’t afraid of telling Hearst’s story in the guise of media mogul and onetime New York gubernatorial candidate Charles Foster Kane, even in spite of the legal challenges that were expected to come out of it. And those legal challenges were anticipated largely because the finished project was foreseen as likely being highly unflattering to one of the most powerful men in America.

Why unflattering? Because Hearst had a number of skeletons in his closet (as well as some that were hiding in plain sight but that went largely uncensured). For Mank’s part, he believed that those egregious transgressions desperately needed to be exposed, especially since many went against his sensibilities and affected those whom he cared about personally. Thus began his mission to pen the screenplay that would fulfill those objectives.

[caption id="attachment_11946" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Writer-actor-director Orson Welles (Tom Burke) prepares to film his debut feature, “Citizen Kane,” what would become a cinematic classic, as chronicled in the back story saga, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

Writer-actor-director Orson Welles (Tom Burke) prepares to film his debut feature, “Citizen Kane,” what would become a cinematic classic, as chronicled in the back story saga, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

The story of how Mank’s script came into being is told through a series of flashbacks dating back to the early ʼ30s. Having been in Hollywood for a few years, he became a big fish in the pond rather quickly as one of the highest paid writers in town. He had also amassed enough clout to become a major recruiter of “new” talent, enabling him to bring to Hollywood a number of his former colleagues, such as writer Ben Hecht (Jeff Harms). Hecht, in turn, tapped the talents of scribe Charles Lederer (Joseph Cross), who soon became friends with Mank. Little did Mank realize at the time that his association with Lederer would open doors for him that he never expected.

One fateful weekend, Lederer invited Mankiewicz to join him for a visit to see his aunt, a prospect Mank initially viewed with little enthusiasm. However, that changed when Mank found himself at San Simeon, Hearst’s opulent California estate, home of the mogul and his longtime mistress, Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), Lederer’s aunt. That weekend visit introduced Mank to Hearst’s world, setting in motion the basis for the script of “Citizen Kane.”

Through subsequent flashbacks, viewers come to learn how and why Mank grew to despise Hearst, despite the fondness he developed for Davies, with whom he became good friends (somewhat to the consternation of Mank’s loyal but long-suffering wife, Sara (Tuppence Middleton)). Mank saw Hearst as a manipulating, self-serving schemer who unhesitatingly shifted his views whenever it became convenient or in his own best interests, with little consideration for who it would affect and how.

[caption id="attachment_11947" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried, left), mistress of newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, strikes up a friendship with screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman, right) who’s about to pen a script in which she provides the inspiration for a principal character, as seen in the “Citizen Kane” back story saga, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

Actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried, left), mistress of newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, strikes up a friendship with screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman, right) who’s about to pen a script in which she provides the inspiration for a principal character, as seen in the “Citizen Kane” back story saga, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

For instance, the onetime-populist Hearst grew progressively more conservative with age, doing everything he could to thwart the efforts of progressives whom he once claimed to support. This became apparent during the 1934 California governor’s race in which Hearst undercut the campaign of Socialist-turned-Democratic Party candidate Upton Sinclair (Ben Nye) by sanctioning propaganda films claiming that the challenger to Republican incumbent Frank Merriam was seeking to turn the state into a haven for Communists. This effort was a collaboration cooked up by Hearst in conjunction with MGM Studio Chief Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) and producer Irving G. Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley). The offer to make these films was extended to would-be filmmakers like cameraman Shelly Metcalf (Jamie McShane) in exchange for future directorial opportunities, breaks these aspiring auteurs might not otherwise get. The films presented a skewed view of Sinclair’s campaign and ultimately contributed to costing him the race.

This practice upset Mank for various reasons. It went against his personal politics. It left him disillusioned about MGM, his employer at the time, especially the company’s aggressive solicitation of his support for its anti-Sinclair effort. It saddened him about the devastating impact it left on his friends who played along with Mayer and Thalberg, leaving them feel as though they had made deals with the devil by abandoning their principles for personal and career gains. And, when Mank learned that all of this occurred with Hearst’s blessing, it made him realize just how truly dangerous this maniacally powerful individual was. It also reinforced his view of Hearst as a political turncoat, calling into question the populist support he once allegedly embraced and thereby exposing his hypocrisy.

When Mank finished his script, he was proud of his accomplishment, believing it to be the best work he had ever done. Welles concurred, though he noted that there were some portions that could use some revision. But not everyone agreed. Mank gave copies of the script to others to read, such as Lederer, Davies and his younger brother Joseph (Tom Pelphrey), also a writer-producer at MGM. And, as much as they admired the writing, they saw the screenplay as an act of professional suicide, one that would probably get him blackballed in Hollywood and expose him to all manner of legal trouble.

Mank disagreed. Having always seen himself as freewheeling, opinionated, outspoken, and, most of all, truthful, Mank didn’t care about such threats. What’s more, he was so gratified with what he had produced that he even sought to renegotiate his deal with Welles: He wanted credit for his writing, a condition that went against his original agreement in which Welles was to get all of the recognition for the project as director, actor and writer. Needless to say, Mank’s request did not sit well with the boss. But, if the project were to move ahead, it was a concession that Welles would have to make, even if it would cost the collaborators their friendship and professional association.

[caption id="attachment_11948" align="aligncenter" width="350"] MGM Studio Chief Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard, left) and producer Irving G. Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley, right) quietly play a significant role in promoting the political agenda of powerful newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst as seen in the new Hollywood drama, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

MGM Studio Chief Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard, left) and producer Irving G. Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley, right) quietly play a significant role in promoting the political agenda of powerful newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst as seen in the new Hollywood drama, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

The finished product, unfortunately, was a box office flop, as Hearst did everything he could to sabotage its theatrical run. What’s more, the film has been a source of ample speculation over the years, both in terms of who Charles Foster Kane was actually based on and which of the script collaborators was responsible for what in the final cut. However, despite the issues involved in bringing “Citizen Kane” to life, the process its creators went through nevertheless led to the birth of a cinematic classic, one that was innovative in countless ways, set new filmmaking standards and opened the door to new opportunities to future directors. And, even though Welles and Mank had their differences in the end, they shared an Oscar for best original screenplay for their work, the only statue that the film captured out of its nine Academy Award nominations.

It should be noted that this film is based on a true story, so its narrative is not to be construed literally but as a collection of speculative re-creations. That’s important to bear in mind considering that there may not be universal agreement on how events actually played out between Mank and Welles. There’s also disagreement about whom the story of “Citizen Kane” is based. As I noted in an end note to my review of that classic film in my most recent book, Third Real: Conscious Creation Goes Back to the Movies, Charles Foster Kane was also said to be patterned after Hearst’s fellow editors and publishers Joseph Pulitzer, Herbert Bayard Swope, and Alfred Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe, with separate accounts claiming the character was based on Chicago industrialists Samuel Insull and Harold McCormick. That aside, though, “Mank” appears to conform with what Mankiewicz asserted was the truth in his own mind, the basis for the discussion that follows.

It’s been said that honesty is the best policy, and I think most people would agree with that. Mank appeared to believe in it, and he made it is his mission when it came to telling the story of Hearst and his cinematic alter-ego. Considering what was alleged to have transpired in Hearst’s life, one could say Mank was justified for drawing it to the public’s attention. The success that came from this effort is apparent in the quality of his finished screenplay, as well as the accolades that it received once translated to film.

Mank’s success was an outgrowth of his belief in being authentic, of pursuing and sharing what he saw as a truth that the public needed and deserved to know. The power of that belief made possible what resulted, the end product of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains the reality we experience stems from those notions that we hold most dear. Mank may have never heard of this practice, but, given what he accomplished, he nevertheless appeared to have a good handle on its principles.

[caption id="attachment_11949" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Loyal but long-suffering wife Sara Mankiewicz (Tuppence Middleton) has her hands full with the chronic gambling and drinking vices of her husband, screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz, as seen in the new Hollywood drama, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

Loyal but long-suffering wife Sara Mankiewicz (Tuppence Middleton) has her hands full with the chronic gambling and drinking vices of her husband, screenwriter Herman J. “Mank” Mankiewicz, as seen in the new Hollywood drama, “Mank.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.[/caption]

Mank’s achievements are attributable to a number of key beliefs. For instance, he saw himself as an open book, and he tended to be a straight shooter, even if what he had to say wasn’t what others wanted to hear. That kind of personal integrity and authenticity carry a lot of weight and are capable of yielding results that are hard to argue with. Likewise, Mank had a firm handle on his writing ability. He knew he was a master of the craft and was able to wield his pen like both a delicate paint brush and a sharpened sword, all the time making his work look effortless. It’s no wonder that the strength and power of those beliefs produced the outcomes that they did.

Of course, there were those at the time and in the ensuing years who doubted his contentions. They labeled his work a personal vendetta against Hearst after being exiled from his subject’s inner circle, and one could argue that such claims might indeed have some merit. They often cited his drinking and gambling as reasons for doubting his credibility. But, despite these issues and the criticism they generated, Mank never backed off from calling things as he saw them, both when it came to himself and others, a penchant for being honest that, again, is hard to argue with. Because of his integrity in this regard, especially when it came to himself, it’s difficult to take issue with it when it came to how he employed it in his characterization of others, no matter how rich, powerful and respected they may be.

Given Mank’s beliefs and the qualities they engendered in him, it’s clear that he was in touch with practicing his value fulfillment, the conscious creation concept associated with being our best, truest selves for fostering the betterment of ourselves and those around us. One could even call this living out our destiny. But, no matter how we semantically characterize this principle, and regardless of how eloquently or coarsely it may express itself, what’s most important is how authentically and effectively it manifests. If his subject’s transgressions had been allowed to go by unaddressed, one could argue that we may not be as circumspect or skeptical of those deserving of legitimate suspicion. Indeed, there’s something to be said for the whistleblowers of society, no matter how brash they might appear – or how unpopular they might become because of it.

David Fincher’s colorful back story examining how the “Kane” screenplay came together harkens back to the lavish productions of old Hollywood with all the trimmings. Its gorgeous black-and-white cinematography and its slate of stellar performances, including those of Oldman, Seyfried, Howard and Dance, remind us of an era gone by and shed light on one that most of us in the general public may have never known existed. Nevertheless, despite these strengths, one can’t help but wonder why many moviegoers would care about a picture like this. Unless one is a diehard classic movie buff, a Welles aficionado or a student of 1930s left-wing politics, “Mank” simply may not have much to offer the average viewer, especially with the film’s many inside (and unexplained) references to these subjects, its ample “Kane” trivia and the details of the lives of those who inspired its storyline. This is by no means a bad picture (though it is a little slow to get started), but it may prompt many to wonder about its reason for being – and leave them pining for Mankiewicz’s handiwork instead. This Netflix original, which is generating considerable awards season buzz, had a brief theatrical run and is now available for online streaming.

Getting at the truth of a matter can be challenging, especially when those seeking to conceal it make every effort to keep it under wraps. Thankfully, though, there are those who are committed to seeing it reach the light of day – and in full public view. Such champions may not always be saints, but their intents are generally sincere in their efforts to enlighten us all. And if that takes raising a little Cain, then so be it.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Saturday, December 12, 2020

‘Mank’ wrestles with matters of integrity, truth

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment