The Chicago International Film Festival recently completed its 2020 edition in its first-ever all-virtual format. With moviehouses just now beginning to reopen due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this alternative approach made it possible for the Festival to go forward, and it worked remarkably well, enabling viewers to screen a variety of films while remaining safe at home or in the comfort of their vehicles at its drive-in performances. As has been the case with other such events this year, this is a viable approach well worth considering for future programs, even without the threat of a pandemic. It makes it possible to offer the Festival’s films to a wider audience and provides flexible viewing conditions, benefits not necessarily available when presented exclusively in theatrical venues.

Because of this new format, I was able to screen a greater number of films than I have in the past. In total, I watched 18 feature offerings, which are reviewed below. Some of these offerings will subsequently be featured in expanded reviews on this site in the near future.

“Apples” (“Mila”) (Greece/Poland/Slovenia) (5/5) (*****)

Director Christos Nikou is off to a fine start with his debut feature about an amnesia sufferer (Aris Servetalis) who struggles with trying to get his memory back while simultaneously attempting to get on with his life in case he can’t. This suspenseful, nuanced and engaging meditation on the nature of memory and the selectivity of its retention will keep viewers guessing from start to finish, all the while serving up heaping helpings of wry humor and cleverly dangling clues before our eyes that may or may not prove integral to solving the mystery of this intriguing conundrum. The film mirrors the eccentricity of directors like Yorgos Lanthimos and Charlie Kaufman, presents a puzzle not unlike that found in Christopher Nolan’s “Memento” (2000), and successfully incorporates the kind of deadpan laughs characteristic of releases like Hal Ashby’s “Being There” (1979). The film’s inventive, tautly assembled script, written by Nikou and Stavros Raptis, deservedly captured the Festival’s Silver Hugo Award for best screenplay. Indeed, if this is what Nikou has to offer in his first major outing, I can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.

“The Columnist” (“De kuthoer”) (Netherlands) (5/5) (*****)

In an age when anyone seems to feel he or she can say anything about anyone on social media without retribution, it’s easy to understand how someone aggrieved might lose it and want to fight back. So it is for the columnist of a popular Dutch periodical (Katja Herbers) who comes under attack from all directions in an assault of unfair (and patently untrue) cyber-bullying – that is, until she decides to fight back using more than just her words. This expertly directed, superbly well acted macabre comedy packs quite a laugh- and horror-filled punch, skillfully knowing when to push the tastefulness envelope and when to pull it back, all tinged with just the right amount of camp and social commentary. There is a slight tendency toward heavy-handedness in a few spots, especially near the end, but director Ivo van Aart’s skillful hand keeps it from getting out of control and turning into a lecture. A real Dutch treat that shouldn’t be missed.

“Kubrick by Kubrick” (France/Poland) (5/5) (*****)

This positively superb documentary about the life and career of legendary director Stanley Kubrick not only does justice to the life of the artist, but also does justice to itself as a tremendous piece of filmmaking. Based on rare audio interviews with the auteur by writer Michel Ciment, director Gregory Monro’s homage to this iconic talent features a wealth of well-chosen clips from most of Kubrick’s pictures (“Paths of Glory” (1957), “Spartacus” (1960), “Dr. Strangelove” (1964), “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), “Barry Lyndon” (1975), “The Shining” (1980), “Full Metal Jacket” (1987), “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999)). It also includes incisive archival interview footage with those who worked with him, including actors Jack Nicholson, Peter Sellers, Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Sterling Hayden, Malcolm McDowell, Shelley Duvall and R. Lee Ermey, as well as behind-the-scenes crew members and noted film critics. The documentary’s impeccable editing and inventive production design link its various segments in ways that pay a fitting tribute to its subject’s work, reverently echoing Kubrick’s style and reinforcing the themes and perspectives that made his films so original and unforgettable. For fans of the filmmaker, this is absolute must-see material.

“New Order” (“Nuevo orden”) (Mexico/France) (5/5) (*****)

In a modern-day version of Mexico, all hell breaks loose when class-based and racially driven riots erupt in the streets, pitting the nation’s sharply divided haves and have-nots against one another in violent urban struggles. While the lines of the warring factions are clearly drawn (and, some might say, perhaps a little too stereotypically at that), the film nevertheless effectively captures the searing frustration felt by the underprivileged, not only in Mexico but globally. Director Michel Franco’s latest will probably be a difficult watch for most viewers, as its frightening narrative doesn’t hold much back (though, thankfully, it successfully avoids the trap of becoming gratuitous, even if by only a slim margin). The message here is one not to be ignored, especially in the wake of events seen across the U.S. in the summer of 2020. We can only hope that this is not a sign of things to come, both on the screen and in the streets.

“And Tomorrow the Entire World” (“Und Morgen die ganze Welt”) (Germany/France) (4/5) (****)

When a first-year law student (Mala Emde) joins an Antifa commune in Berlin to combat rising right-wing hate groups in Germany, her commitment gets tested, especially when she begins falling for the organization’s extremist leader (Noah Saavedra). Is she fighting for a cause, supporting a romantic interest or some of both? Those are the issues she wrestles with as she gets more deeply involved than she probably ever thought she would be. While a bit predictable and a tad meandering at times, director Julia von Heinz’s latest nevertheless capably explores questions of involvement, both socially and romantically, as well as the naïvete of youth and the difficulty of hard choices in the face of inexperience. The picture’s excellent ensemble earned the film the Festival’s Silver Hugo Award for best cast, a well-deserved honor. The film’s strengths aside, however, this may be a hard watch for some viewers, but, like fellow Festival offering “New Order” (see above), its relevancy in today’s sociopolitical climate couldn’t be more timely.

“Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time” (“Felkészülés meghatározatlan ideig tartó együttlétre”) (Hungary) (4/5) (****)

Director Lili Horvát’s second feature presents an ominous, atmospheric tale of romantic obsession and the struggle to grasp the true state of one’s reality, all wrapped up in a psychological thriller. The film’s edge-of-the-seat quality is successfully sustained for much of its run, but, regrettably, it winds up feeling somewhat incomplete and unfulfilling by picture’s end. Natasa Stork’s fine lead performance as a troubled neurosurgeon, the picture’s exquisite cinematography and its clever editing will definitely keep viewers guessing for much of the film, but whatever intrigue capital the director has amassed by the final act is somewhat squandered on a less-than-satisfying outcome. Still, for her efforts, Horvát received the Festival’s Gold Hugo Award in its New Directors Competition, but, for my money, this Hungarian offering comes close but doesn’t quite hit the mark as squarely as it could have.

“The Prophet and the Space Aliens” (Israel/Austria) (4/5) (****)

Director Yoav Shamir’s entertaining documentary about self-proclaimed UFO Prophet Rael and his extraterrestrial-based religion tactfully walks a fine line between journalistic objectivity and tongue-in-cheek satire about the life of a former aspiring pop star-turned-race car driver-turned-high priest of an emerging new belief system. In telling this story, Shamir is careful not to be a softballing spokesperson for the cause nor a pitbull reporter seeking to cynically tear it to shreds, presenting a fair and balanced examination of his subject and his movement, posing probing questions when needed but ultimately letting viewers make up their own minds. If nothing else, his interviews with many of Rael’s followers reveal a loving and devoted band of admirers who firmly believe in the positive and uplifting messages of the faith and how those principles have brought them happiness, freedom and fulfillment in ways that they don’t believe would have attainable through other means. Thought-provoking and soul-searching in nature, the film is a fun yet respectful look at a movement that may be a little out of the ordinary and most definitely out of this world.

“ʼTil Kingdom Come” (“Ad Sof HaOlam”) (Israel/U.K./Norway) (4/5) (****)

This simmering documentary about the unlikely bond between American Evangelicals and Israeli conservatives to manipulate policies aimed at fulfilling Biblical prophecy grows scarier with each passing minute. With an agenda of expediency and literal adherence to scripture wrapped around a fundamentally hypocritical core, the undertakings of this potentially calamitous alliance should make everyone shudder. Thankfully, director Maya Zinshtein’s incisive offering makes that abundantly clear. The film could have benefitted from a little more back story and the input of some additional experts, given its scant 76-minute runtime. However, what material is there is rock solid and hard-hitting, presented without judgment and letting the content speak for itself – which it does in volumes.

“Twilight’s Kiss” (“Suk Suk”) (Hong Kong) (4/5) (****)

This sensitive gay romance between two seniors (Tai-Bo, Ben Yuen) who have denied their feelings about themselves for decades but are now willing to consider a future together touches on a number of issues pertinent to anyone who is aging but especially to those seeking to forge long-denied same-sex relationships. Despite a few story threads that aren’t explored as fully as they might have been and a somewhat sappy love song soundtrack, the film brims with heartfelt emotion and thoughtfully examines questions crucial to gay seniors, such as same-sex nursing home care, relationships in the face of impending mortality and the acceptance of gay parents by adult children. Director Ray Yeung’s third feature satisfies and even leaves viewers longing for more (something he may want to consider incorporating in future projects).

“Becoming Mona” (“Kom hier dat ik u kus”) (Netherlands/Belgium) (3/5) (***)

This honest, realistic domestic drama examines the dynamics of a family in crisis and an eldest daughter (Tanya Zabarylo) who always tries to do the right thing whenever dysfunction rears its ugly head, even when it comes at a painful emotional cost to her. Though well-acted and capably paced, the story itself is somewhat lacking in originality, not charting any particularly new territory and presenting dilemmas and scenarios we’ve all seen before. While this effort from directors Sabine Lubbe Bakker and Niels van Koevorden may be moving, it’s not especially innovative, leaving viewers wanting something more groundbreaking, despite a relatively solid narrative foundation. “Becoming Mona” certainly passes the time, but it doesn’t leave a particularly indelible mark.

“Dear Comrades!” (“Dorogie tovarishchi!”) (Russia) (3/5) (***)

This re-creation of a 1962 anti-Soviet workers’ strike at an electromotive manufacturing plant in Novocherkassk, Russia brings this obscure but violent historic event to life on a human scale in legendary director Andrey Konchalovskiy’s latest. Gorgeously shot in black and white, the film focuses on the experience of a devout party advocate (Yuliya Vysotskaya) who becomes staunchly disillusioned when the fallout from the event affects her personally and profoundly. Regrettably, the story is so heavy on detail that it becomes talky and tedious at times, especially in its depiction of discussions among Party, KGB and military officials. The fine lead performances of Vysotskaya and Vladislav Komarov help to cover for this shortcoming somewhat, but a judicious degree of snipping to accelerate the pacing would have helped make a good film a great one. For his efforts, though, Konchalovskiy won the Festival’s Silver Hugo Award for best director.

“Gaza Mon Amour” (Palestine/France/Germany/Portugal/Qatar) (3/5) (***)

This touching, whimsical yet tentative love story about a 60-year-old financially strapped Palestinian fisherman (Salim Dau) who falls for a retiring seamstress (Hiam Abbass) plays like an ongoing game of cat and mouse. But, when he unexpectedly “catches” a prized antique Greek statue in his nets, his fortunes take a turn for the better, with a few detours along the way (not to mention the many ongoing challenges of everyday life in Gaza). While the Nasser Brothers’ love-conquers-all tale serves up its share of charm and wit against an unlikely backdrop, a few more laughs certainly would have helped bolster this otherwise-delightful tale. Think of this as a sort of modern-day “Moonstruck” (1987) in the Middle East, and you’ve got a rough idea what this one is all about.

“Mama Gloria” (U.S.) (3/5) (***)

Legendary Black trans female activist Gloria Allen (a.k.a. Mama Gloria) has led quite a remarkable life, as chronicled in this new documentary about her storied 73 years. This Chicago icon of the LGBTQ community has experienced both heartwarming and heartbreaking times in her life, not only in her journey of self-discovery and her various relationships and friendships, but also in her efforts to earn recognition and respect for the trans community, especially at-risk trans women of color. She details the joys of launching her charm school for trans women (and the experience of having had that story made into a play), as well as the anguish of the beatings that she and her peers endured at the hands of the intolerant. While director Luchina Fisher’s documentary feature debut is, on balance, well constructed, it nevertheless could have used better editing in spots, particularly in smoothing out transitions, deleting some extraneous material and expanding on other elements that deserve more attention. Still, Mama Gloria’s inspiring story is one for anybody who feels as if they’re on the outside looking in – and looking to change that for themselves.

“Sweat” (Sweden/Poland) (3/5) (***)

What makes us happy? And are those who are seemingly happy all the time truly the happiest? Those are the questions posed by “Sweat,” the story of a popular online fitness instructor (Magdalena Kolesnik) who seems to have it all together, but does she really? In this age of omnipresent social media, that’s a critical question we all need to ask ourselves, and the film makes a valiant attempt at doing so, but it takes far too long to make its point, taking viewers through considerable seemingly irrelevant flotsam on its way there. While director Magnus von Horn’s second feature deservedly earned the Festival’s Silver Hugo Award for best art direction, it’s rather hard to fathom that the film also captured the Gold Hugo Award as the Festival’s best feature (it’s simply not that good). Indeed, for a better cinematic exploration of the film’s central message, watch the vastly underrated American offering “Ingrid Goes West” (2017) instead.

“Memory House” (“Casa de antiguidades”) (Brazil/France) (2/5) (**)

Ambitious, haunting and hypnotic but ultimately wildly unfocused, this debut feature from director João Paulo Miranda Maria tries to cover too much ground and ends up doing more to baffle viewers than to enlighten them. In this symbolic and surreal examination of the de facto state of colonialism existing in contemporary southern Brazil, the narrative attempts to explore the ethnic, sociopolitical and inequality issues affecting the region’s minority population as told through the eyes of a Black dairy worker (Antonio Pitanga). Ethereal imagery and inventive cinematography get the picture off to a promising start, but the film loses its way as it goes on, pursuing one unresolved tangent after another and eventually going completely off the rails in the final act. While it’s commendable that the filmmaker doesn’t spoon-feed his audience, he nevertheless seems to expect them to possess an intimate knowledge of Brazilian politics and culture to grasp his message. That may be fine for a screening to a regional viewership, but, for an international film festival (or mainstream distribution, if one should result), that’s expecting a lot from the audience just to be able to understand what he’s trying to say. In spite of these problems, however, the film somehow managed to capture the Roger Ebert Award in the Festival’s New Directors Competition.

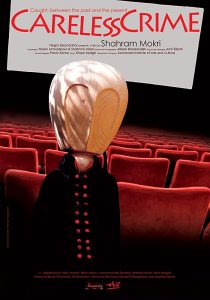

“Careless Crime” (“Jenayat-e bi deghat”) (Iran) (1/5) (*)

Handily one of the most audaciously pretentious pieces of cinematic crap I have seen in ages. “Based” on a tragic act of arson in an Iranian moviehouse shortly before the 1979 overthrow of the Shah – a premeditated terrorist attack on so-called decadent Western cultural influences – “Careless Crime” echoes that story and sentiment in a modern-day theater presenting a film by the same name. That movie-within-a-movie, in turn, echoes the lives of present-day theater owners and patrons attending a screening that has been targeted for attack by a quartet of contemporary arsonists, while also giving nods to the anniversary of the 1979 moviehouse incident, creating a multi-layered, folded-over time loop involving the integration of the three primary story threads. I found director Shahram Mokri’s overly glib, too-clever-for-its-own-good offering to be stunningly baffling, frequently pointless, and, frankly, lacking in respect for the original tragedy. I might have cut this film more slack if it weren’t directly referencing an actual event in which nearly 500 people lost their lives, but a project that so cavalierly springboards off of a tragedy like that just leaves a bad taste in my mouth, as I would think it should for most viewers (that is, those who’d be willing to waste 2:15 of their lives watching this celluloid mess). Add to that some rather cheesy production values and a desperate need for excessive editing, and you’ve got something that’s really not worth your while, despite its inexplicable capture of the Festival’s Silver Hugo Jury Prize Award.

“Sleep” (“Schlaf”) (Germany) (1/5) (*)

What starts out as an ambitious suspense tale turns tedious not far into the story as it introduces so many different unresolved tangents that it becomes difficult to decipher and even more of a chore to care about. With references to lucid dreaming, German folklore, and past and present right-wing German politics, director Michael Venus’s debut feature becomes so convoluted that it leans laughable when it’s not being a big bore (or “boar,” given its repetitive woodland animal imagery). What’s most regrettable, though, is that this supposed horror thriller fails to live up to its billing by coming up short on its primary mission – being scary, something it most definitely is not. Sadly, when watching a film becomes too much work to enjoy the experience, it’s really not worth the time or effort, and so it is with this big snooze.

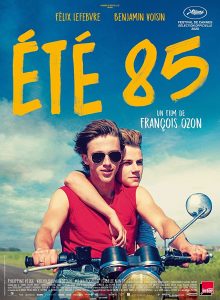

“Summer of 85” (“Été 85”) (France/Belgium) (1/5) (*)

If I could give this a score of less than 1, I would. Writer-director François Ozon’s utterly preposterous, vanilla-encrusted “forbidden gay romance” tale is so unbelievably dated and clichéd that it’s unfathomable anyone would have wanted to back this project. With a narrative that plays like so many “homosexual dramas” of the ʼ60s and ʼ70s in which something bad inevitably happens to someone just by virtue of being gay, “Summer of 85” is a trite throwback to those cautionary tales of yore (and, even at that, it’s almost totally lacking in the suspense that made some of those stunningly judgmental, overly prejudicial releases at least somewhat entertaining in their own excessively intolerant way). There is something of a modest camp factor present here, but not nearly enough to make this the parody of those old melodramas that it could have been. Skip this one at all costs.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Sunday, October 25, 2020

Wrapping Up the 2020 Chicago Film Festival

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment