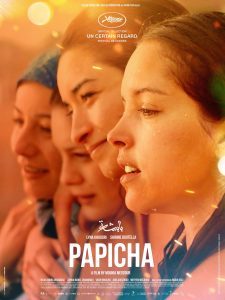

“Papicha” (2019 production, 2020 release). Cast: Lyna Khoudri, Shirine Boutella, Amira Hilda Douaouda, Yasin Houicha, Marwan Zeghbib, Zahra Doumandji, Meriem Medjkrane, Samir El Hakim, Nadia Kaci, Lina Boudraa, Khaled Benaissa, Malek Ghellamat. Director: Mounia Meddour. Screenplay: Mounia Meddour and Fadette Drouard. Web site. Trailer.

Taking risks can be a scary prospect, and the bigger the risk, the greater the potential peril. However, the same is true when it comes to the prospective risks involved. Of course, it takes considerable resolve to face such conditions, but that’s entirely possible, as showcased in the inspiring new period piece drama, “Papicha.”

For those who lived through the perils of the 1990s Algerian Civil War – a time that came to be called “the dirty war” or “the black decade” – the fallout from the struggle affected virtually every aspect of daily life. For some, that included implications whose impact was felt in highly personal ways, often involving things that bore little or no connection to the kinds of matters that typically come up for contention during armed conflict and sociopolitical debates. And, in this case, some of the worst torment was borne by the nation’s women.

After winning a nearly eight-year War of Independence in 1962, the former French colony emerged as a largely secular state with socialist leanings. Over time, though, the North African nation began to push for a return to the Islamist roots of its predominantly Arab population. And, by the 1990s, powerful fundamentalist factions fought to obtain political control, eventually pitting strict Muslim traditionalists against their more liberal Westernized counterparts. As the two sides vied for power, a brutal civil war broke out that killed upwards of 150,000 (some say more) and displaced countless refugees.

As the war raged internally, fundamentalists placed extreme coercive pressure on their secularized counterparts to conform to traditional Islamic dictates. Again, the greatest coercion was imposed on women, especially those who embraced the “decadent” and “immoral” ways of the West and who openly defied the far more restrictive doctrinal conventions that were supposed to be accepted without question. The euphemistically characterized requirement that women dress and carry themselves “modestly” was, in fact, an orchestrated effort to place them under the thumb of a male-dominated power structure that treated them like property, and those seeking to assert control often did whatever they believed was necessary to make this possible, employing the services of both male and female followers. Yet, for all the strong-arm tactics inflicted upon the women of Algeria, there were those who would have none of it, despite the dangers involved in openly resisting such efforts.

That’s where the papicha segment of society came into play. “Papicha” is an Algerian term used to describe an intelligent, confident, liberated, often-stylish and attractive woman. For all practical purposes, one could consider papichas the feminists of this North African nation, and that is how many have typically viewed themselves. However, during the Civil War, fundamentalists often used the term in a less flattering way, almost on par with “harlot” or “whore.” Nevertheless, many women who saw themselves in the more traditional sense of the term tended to let the derogatory label slide off their backs, taking pride in their self-assurance and courageously asserting themselves in their convictions.

That kind of strident confidence characterizes the young women in this story, nearly all of them students at an all-female university in Algiers, the nation’s capital. The most outspoken among them is Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri), a budding fashion designer who comes up with stylish creations for women who frequent the city’s nightclubs. Working with her friend, Wassila (Shirine Boutella), Nedjma’s underground dressmaking operation grows popular and develops quite a reputation.

[caption id="attachment_11533" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, center), a budding fashion designer, seeks to make a statement with her creations during the tyranny of the 1990s Algerian Civil War in the inspiring new period piece drama, “Papicha.” Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, center), a budding fashion designer, seeks to make a statement with her creations during the tyranny of the 1990s Algerian Civil War in the inspiring new period piece drama, “Papicha.” Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

However, carrying out this venture has more than its share of risks. Getting to the clubs is often an ordeal in itself; Nedjma and Wassila must disguise themselves in traditional garb, and their rides to the nightspots frequently take them through military checkpoints. Then there’s the matter of even being able to leave the university premises; to gain access to the outside world after dark, Nedjma must pay off the college’s seedy gatekeeper, Mokhtar (Samir El Hakim), to keep him from talking, a fee that he keeps raising, even suggesting that it can be paid with more than just money. And, of course, there are probing questions from fabric suppliers who wonder what Nedjma needs with all of the bright and fancy cloth she buys – materials that she couldn’t possibly be using to sew the traditional black hijabs worn by compliant Muslim women. Still, Nedjma believes in what she’s doing, not only for the fulfillment she gets from designing her creations, but also for the personally defiant statement she makes through her efforts.

Nedjma differs from her classmates in other ways, though. Given the prevailing conditions in Algeria, many of them are looking for ways to leave the country, convinced that things will only deteriorate further. Her friend Kahina (Zahra Doumandji), for example, wants to emigrate to Canada; she sees herself being like the many others who live in “the waiting room” that is Algiers, biding their time until exit visas come through, a situation not unlike that depicted in the title location of the World War II screen classic “Casablanca” (1942). Others hope to marry themselves off to wealthy spouses who will take them away from the conflict and the coercion, either out of the country or in secluded estates where they can sustain their secularized lives out of sight. And some have agreed to capitulate to the winds of change, such as Samira (Amira Hilda Douaouda), an intelligent but pious young woman who’s already agreed to submit to the will of her husband-to-be in their impending arranged marriage, including giving up the studies she needs to complete her degree program.

Nedjma will have none of that, though. She’s determined to stay in Algeria, the homeland she loves, but without compromising. In fact, in some ways, she’s rather militant about the imposition of fundamentalist rule, unabashedly engaging in such acts as vandalizing publicly plastered posters compelling women to don hijabs, the “proper” garb for outside the home, notices that even detail how they should be worn. She willingly participates in shouting matches with fundamentalist women when they try to tell others – including male university professors – how to behave. And she even refuses to ingest the dining hall food that has been “dosed” with dangerously high levels of the epileptic sedative potassium bromide, a deliberate effort to reduce “female urges.” It’s a substance that can have hazardous side effects over time, and this practice goes on unabated under the oblivious eye of the university’s head mistress, Madame Kamissi (Nadia Kaci).

[caption id="attachment_11534" align="aligncenter" width="350"] While visiting her mother, budding fashion designer Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, left) learns about the tradition of Algerian haiks, garments intended to accentuate feminine beauty, in director Mounia Meddour’s feature film debut, “Papicha.” Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

While visiting her mother, budding fashion designer Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, left) learns about the tradition of Algerian haiks, garments intended to accentuate feminine beauty, in director Mounia Meddour’s feature film debut, “Papicha.” Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

Under these circumstances, Nedjma has much to contend with, but she still manages to find the time to work on her designs. On a visit to see her mother and her sister, Linda (Meriem Medjkrane), she becomes captivated with the design possibilities for creating haiks, a traditional Algerian garment crafted from a single large, rectangular swath of fabric whose distinctive qualities are crafted using different forms of folds and draping. Unlike hijabs, whose intent is to promote modesty and conformity, haiks are designed to celebrate beauty, a form of clothing that flatters, rather than degrades, women. Linda and mom show Nedjma the various ways that haiks can be worn, some of which are purely decorative and others of which are ceremonial. There are even “practical” options, such as haiks fashioned to conceal weapons, a form of the garment that was often worn by female freedom fighters during the Algerian War of Independence.

Clearly, Nedjma lives her personal power. But her confidence in that power is tested when she experiences a family tragedy, one so severe that it nearly saps all of her resolve. Rather than be deterred, however, she redoubles her efforts and makes an important decision: She vows to stage a runway-style fashion show of her designs, all of which are different styles of haiks, with her friends and classmates serving as models. In essence, she seeks to make a fashion statement that makes a statement in itself.

Thus begins Nedjma’s campaign to put on her show. But, as her plans unfold, they nearly derail as she’s met with constant setbacks, challenges that push her to the limits of her ability to carry on. Nevertheless, given how far she’s come thus far, there’s no stopping the papicha from living up to her reputation – and showing the world just what she can do.

Accomplishments like those tackled by Nedjma and her peers are truly inspiring, especially under the conditions they faced. Many may have backed away because they saw the challenges as too daunting, while others may have given up out of intimidation. But not Nedjma; she moved forward because she believed in what she set out to do, and the power of those beliefs helped to make her goals attainable. Such is what happens when we set our minds to effectively employing the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these intangible resources in manifesting the reality we experience.

[caption id="attachment_11535" align="aligncenter" width="350"] When confronted by fundamentalist insurgents critical of her decadent Western ways, fashion design student Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, center) stands her ground against those seeking to quash her plans for staging a fashion show in “Papicha.” Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

When confronted by fundamentalist insurgents critical of her decadent Western ways, fashion design student Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, center) stands her ground against those seeking to quash her plans for staging a fashion show in “Papicha.” Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

In taking on such a task, Nedjma needed to galvanize herself in her intents. For starters, given the constant threat of insurgents, who often operated clandestinely and launched surprise assaults, Nedjma had to conquer her fears and seek to live heroically, for nothing is gained without the willingness to move forward with confident, unshackled conviction. This was true for her not only in confronting terrorists and their shrill female collaborators, but also in dealing with the many chauvinists and misogynists in her life, such as shady product suppliers and, of course, the oily college gatekeeper. Fortunately, the strength of Nedjma’s beliefs, as well as the faith she placed in them, allowed her to overcome these obstacles.

What may have helped Nedjma the most was her belief in making a statement through her creations. Designers nearly always seek to do that when it comes to their clothes, though primarily from an aesthetic standpoint. In Nedjma’s case, however, she sought to come up with designs intended to go beyond mere appearances; she wanted her fashion statement to make a statement of its own. By designing a line of clothes consisting entirely of haiks, garments whose inherent intent had always been to accentuate feminine beauty, she was bucking the trend that fundamentalists were looking to impose on Algerian women by forcing them to wear hijabs, outfits purposely aimed at making them subservient. This symbolic protest was important in light of the power that symbols have in influencing the minds of others, and, at a time when women were being systematically denigrated, Nedjma’s creations provided a powerful backlash against such attempts at organized tyranny.

Of course, it helped that Nedjma had a great deal of help from those around her. Mutual undertakings like this often result in successful outcomes because of the combined power of like minds (and beliefs). Acts of co-creation frequently lead to success, even if only fleeting, in the face of dire conditions, making an impact that ripples outward into other segments of society – especially those most in need of hearing the message that’s being conveyed.

[caption id="attachment_11536" align="aligncenter" width="350"] With her friends by her side, fashion design student Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, right) seeks to put on a fashion show during the 1990s Algerian Civil War in “Papicha,” now available for first-run online streaming. Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

With her friends by her side, fashion design student Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri, right) seeks to put on a fashion show during the 1990s Algerian Civil War in “Papicha,” now available for first-run online streaming. Photo courtesy of Distrib Films US.[/caption]

“Papicha” offers viewers an engaging tale about a conflict that’s received little cinematic attention, told from a unique narrative perspective. This fact-based dramatic feature film debut from director Mounia Meddour, based in large part on the filmmaker’s own experiences living in Algeria during the Civil War, tells a compelling and moving story, one whose message is a fiery and inspiring manifesto for women whose rights and very being are under attack by those seeking to subvert the innate individuality that is their birthright. While some elements of the story seem a bit forced, largely due to the lack of a sufficient back story (viewers may want to read up about the conflict somewhat before viewing the film), the film nevertheless raises a variety of intriguing thematic issues using an unlikely but highly inventive form of symbolism, a truly pleasant surprise that emerges from a cinematically innovative premise. Although “Papicha” is just now coming into general release (available through first-run online streaming), the picture has been on the film festival circuit for some time. It has earned its share of recognition as well, including a nomination in the Un Certain Regard competition at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival.

Standing our ground in the face of oppression requires tremendous courage, conviction and fortitude. Indeed, when our persecutors line up before us, the potential always exists that we may be shaken to our core. But that needn’t be the case if we genuinely believe in ourselves. And, if we do it right, like Nedjma, we just might make a statement in the process.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Wednesday, June 10, 2020

‘Papicha’ showcases the rewards of risk

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment