“Aniara” (2018 production, 2019 release). Cast: Emelie Jonsson, Bianca Cruzeiro, Arvin Kananian, Anneli Martini, Jennie Silfverhjelm, Emma Broomé, Jamil Drissi, Leon Jiber, David Nzinga, Peter Carlberg, Dakota Trancher Williams, Otis Costillo Ålhed, Dante Westergårdh. Directors: Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja. Screenplay: Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja. Source Material: Harry Martinson, poem, Aniara. Web site. Trailer.

Starting over can seem like a dual-edged sword. In some ways, it may appear to be a tremendous opportunity to begin afresh. In other ways, though, we might feel devastated, completely overwhelmed by what we find ourselves up against. And, in the midst of that conundrum, we could be beset by the feeling of being totally adrift, unable to find our way, emotions not unlike those experienced by a group of space-weary travelers in the existential sci-fi offering, “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats.

With Earth becoming increasingly uninhabitable, a group of intrepid colonists sets out to stake a new future on Mars. They make the three-week journey to the Red Planet aboard enormous spaceships, such as the Aniara, which is really more like a cruise liner than a lifeboat. The craft is equipped with an array of luxurious comforts, including 21 restaurants, a shopping concourse, a gym and spa, and numerous other recreational activities. But perhaps one of the ship’s most intriguing amenities is the Mima Hall, a facility featuring a highly specialized form of artificial intelligence that’s able to tap into the consciousness of those who link with it. The Mima reads the thoughts, minds and memories of passengers, providing them with vivid, tailor-made virtual reality images of nature, particularly those of a time when the Earth was pristine. In this way, the Mima is designed to put the colonists’ minds at ease, assuaging any anxieties they might have about space flight, smoothing the transition to their new lives and leaving them with positive thoughts about the world they’re fleeing.

[caption id="attachment_11623" align="aligncenter" width="350"] The spaceship Aniara prepares to embark on its journey to Mars in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

The spaceship Aniara prepares to embark on its journey to Mars in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

The Mima is administered by a specially trained host and technician, the Mimarobe (or MR) (Emelie Jonsson). She oversees the Mima’s operation and attends to the needs of passengers who have trouble adjusting to it, enhancing the quality of their experience. With such a soothing technology as this, one might think that the MR has her hands full attending to the needs of many eager users. However, as the Aniara embarks on its journey, there’s surprisingly little interest in the Mima, as most of the colonists are much more interested in partaking of the ship’s more conventional amenities.

Not long after the ship begins its journey, though, circumstances change drastically. When the Aniara is struck by space debris, the ship’s navigation capabilities are disabled, sending it off course and making it impossible for the crew to steer the vessel to get it back on track. The passengers are understandably upset, but the ship’s skipper, Capt. Chefone (Arvin Kananian), assures them that the crew will be able to rectify the problem as soon as the Aniara encounters a celestial body, where a gravitational slingshot effect around said object will enable restoration of the ship’s navigation capabilities, a process that he estimates will take no longer than two years to accomplish. However, for a group of colonists anxious to get on with their lives, two years is a far cry from the promised three weeks.

Given the change in plans, the crew begins making adjustments to operations. Thankfully, certain considerations, like air and food supply, aren’t issues; the ship’s advanced sustainability systems should enable these commodities to be available for a period far longer than two years if need be. However, despite the captain’s assertions that the ship will be able to get back on course, there are those on board who know otherwise, such as the Aniara’s resident astronomer (Anneli Martini), who quietly observes that there are no celestial bodies on the ship’s current trajectory capable of enabling the projected corrective maneuver. What’s more, given the passengers’ doubt about their fate, they start seeking solace in the Mima in numbers far greater than anticipated, overwhelming the MR and the technology she manages. Before long, the astronomer, the MR and the Mima all find themselves in jeopardy they never expected.

[caption id="attachment_11624" align="aligncenter" width="350"] MR, the Mimarobe (Emelie Jonsson), oversees the operation of the Mima, a highly specialized form of artificial intelligence that links its users to tailor-made nature images to provide them with a calming effect, one of many amenities available aboard the spaceship Aniara, as seen in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara.” Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

MR, the Mimarobe (Emelie Jonsson), oversees the operation of the Mima, a highly specialized form of artificial intelligence that links its users to tailor-made nature images to provide them with a calming effect, one of many amenities available aboard the spaceship Aniara, as seen in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara.” Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

Thus begins the saga of the Aniara as it moves through space toward an uncertain future. The story of this lost vessel, told in chapters at various points along its protracted timeline, depicts the many diverse developments that occur along its path. These include both personal stories, such as the MR’s relationships with her lovers, Isagel (Bianca Cruzeiro) and Daisi (Leon Jiber), as well as tales affecting the crew and passengers at large, such as those involving ad hoc incarceration, the emergence of various cults and a charismatic spiritual leader (Jennie Silfverhjelm), rescue efforts, and initiatives aimed at maintaining hope amidst ever-growing despair. And, through it all, everyone concerned is presented with opportunities to discover new things about their individuality, their humanity and their relationship to powers greater than themselves, a true space odyssey if there ever were one.

Given their circumstances, one would probably be hard-pressed to envy the fate of the crew and passengers of the Aniara. With such uncertainty hanging over them, they can’t count on the future they hoped for, let alone one that offers virtually any semblance of comfort or predictability. So what does one do in a situation like this, especially as resources begin to dwindle and familiar forms of consolation start to disappear?

Building a new life from scratch is a daunting challenge to be sure. In many ways, there are no rules (despite the crew’s attempts at trying to maintain an approximation of the civilized life the passengers have always known but that is quickly slipping away). So how does one proceed?

[caption id="attachment_11625" align="aligncenter" width="350"] The Mima Hall, gathering place for users of the highly specialized form of artificial intelligence known as the Mima, provides solace to space-weary travelers in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

The Mima Hall, gathering place for users of the highly specialized form of artificial intelligence known as the Mima, provides solace to space-weary travelers in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

That’s where each individual’s beliefs come into play, for they provide the basis of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting the reality we experience. And, in this case, the passengers and crew must draw upon their beliefs in their most basic form, those that reside in the core of their being, for they will provide the foundation for shaping the framework of the new existence they’re building for themselves. In that regard, they must ask themselves which beliefs will underlie everything that stems from them, as if they’re providing “an operating system” atop which all of their various “applications” will run. Is this to be a reality that draws upon hope-based beliefs for its character? Or will it be one that’s riddled with despair? Those are radically different approaches to the same basic task, methodologies that, in turn, are likely to yield radically different results. What will they choose?

To complicate matters, shaping a new paradigm is an act of co-creation, one in which the influences of multiple participants are involved. And, given the disparate outlooks each of them holds, there’s bound to be considerable contradiction at play, making the realization of a cohesive, integrated whole difficult to achieve. The beliefs of those who try to remain optimistic, such as the MR, clash with those of the naysayers, like the astronomer and Isagel, as well as those who insist on remaining dogmatically practical, such as Capt. Chefone. Is it any wonder, then, that the future of those aboard the Aniara remains in limbo as everyone tries to sort out what they think they want both for themselves and the collective?

Without a doubt, these circumstances present an opportunity to think outside the box, to let our imagination devise beliefs that surpass limitations and enable us to explore possibilities never before dreamed of. On a somewhat mundane level, for example, that becomes visible through the solutions devised to address the practical problems of an everyday life that has been thrown seriously out of kilter. And, on a more sacred plane, that becomes apparent through the various spiritual explorations that the passengers and crew engage in, both through the cults and individual introspection. In either case, not everything may work, but these circumstances at least give everyone a chance to stretch his or her creativity muscles, an opportunity providing them with a chance to become more proficient and more effective conscious creation practitioners.

[caption id="attachment_11626" align="aligncenter" width="350"] MR, the Mimarobe (Emelie Jonsson), overseer of a highly specialized form of artificial intelligence known as the Mima, tries to maintain hope under deteriorating conditions aboard the spaceship Aniara in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara.” Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

MR, the Mimarobe (Emelie Jonsson), overseer of a highly specialized form of artificial intelligence known as the Mima, tries to maintain hope under deteriorating conditions aboard the spaceship Aniara in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara.” Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

However, if we indeed use the power of our beliefs to manifest our reality, one might legitimately ask why the passengers and crew created such dire conditions in the first place. But, as with any creation, the reasons behind our respective materializations are our own, and it’s no one’s place to question our motives. For instance, there may be a desire to learn particular life lessons driving these initiatives, and, in the case of those aboard the Aniara, one could argue that was inherent in their intent from the outset of their voyage – to experience what it would be like to begin a new life off the Earth. Their initial destination may have been Mars, and that plan is obviously now out the window, but the unanticipated journey on which they now find themselves ended up yielding a creation with the same underlying intent – the construction of a whole new life from the ground up. The passengers and crew may have indeed created for themselves circumstances far more challenging than originally envisioned, but the goal is arguably the same. This thus illustrates the phenomenal intrinsic power of our beliefs. It also aptly shows us how we must be careful in wielding that power, because we may end up getting far more than we bargained for.

The film’s various story threads also examine how we deal with certain aspects of life in light of such drastically changed circumstances. For example, “Aniara” explores how to handle the loss of the creature comforts to which we have become so accustomed in the wake of dire new conditions, something the colonists would have had to address in their new lives regardless of whether or not they had successfully reached the Red Planet. Likewise, the picture’s narrative brings to life various aspects of religion – salvation, redemption, confession, surrender, etc. – that many of the passengers are familiar with, giving them firsthand experience in dealing with them on a level they’ve probably never done before. These initiatives could all be considered part of the larger question of the passengers and crew creating a new world for themselves, but, given the prominence these considerations likely occupy in their lives, they could be almost as daunting in and of themselves as the bigger issue being addressed.

All in all, there’s quite a full plate at work here, and one could easily be overcome, as evidenced in the experiences of some of those aboard the wayward vessel. In many respects, the story of the passengers and crew serves as a powerful cautionary tale to those of us facing comparable circumstances. That’s not to suggest that we’re likely to find ourselves on a spaceship headed into unknown regions of the galaxy, but we could experience situations where we’re having to start over and build from the ground up. How will we handle that? Can we sustain our will to endure? Or will we give in to our sense of “despairing” (the translation of the ancient Greek word “aniara” from which the ship ironically derives its name)? We might want to take a cue from those on board the Aniara, for better or worse, to get ourselves started.

[caption id="attachment_11627" align="aligncenter" width="350"] The relationship between MR (Emelie Jonsson, left) and her partner, Isagel (Bianca Cruzeiro, right), undergoes a series of ups and downs when their spacecraft, the Aniara, unexpectedly goes off course in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

The relationship between MR (Emelie Jonsson, left) and her partner, Isagel (Bianca Cruzeiro, right), undergoes a series of ups and downs when their spacecraft, the Aniara, unexpectedly goes off course in the existential sci-fi offering “Aniara,” available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Magnet Releasing.[/caption]

This ambitious existential sci-fi offering, based on a Swedish poem of the same name by Nobel Prize winner Harry Martinson, makes a valiant attempt at transcending the content, substance and style typically associated with other films of the genre. However, due to an underdeveloped script, an overreliance on viewer knowledge of the source material, occasionally uneven pacing and a need for some judicious editing, the picture doesn’t quite rise to the greatness it might have been truly capable of. The film’s impeccable production design, superb special effects and fine performances are augmented by nods to a variety of other sci-fi works, including “Solaris” (2002), “Gravity” (2013), “Passengers” (2016) and Battlestar Gallactica (1978-79, 2005-09), as well as allusions to such diverse offerings as “Midsommar” (2019), “Eyes Wide Shut” (1999), “Tommy” (1975) and various tales of hopelessly adrift seafarers. Its prolific references to matters religious, spiritual, metaphysical, environmental and sociopolitical pepper the story, sometimes effectively, sometimes not so much, resulting in a grab bag of enlightenment, frustration and assorted enigmas. In an age where our own world is seemingly being turned upside-down, the insights of this story – had they been better developed – could have been a godsend to a weary population, providing us all with a new, clearer understanding of where we’re at and where we’re headed. But, unfortunately, “Aniara” comes up short of achieving that goal – and at a time when we could use it most.

When we find ourselves adrift, treading water may help us stay afloat, but it also won’t get us anywhere. And, when we’re lost in the great expanse of the ocean (or the heavens, for that matter), a maneuver designed to merely keep us stationary might not seem like much help. However, it can buy us valuable time to sort out our circumstances to devise a solution that could prove to be a life-saver, a shining beacon of encouragement at a time when all else may seem hopeless.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Friday, July 31, 2020

‘Aniara’ seeks to provide direction to the adrift

Thursday, July 30, 2020

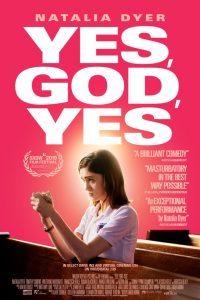

‘Yes, God, Yes’ explores the depths of sex and spirit

“Yes, God, Yes” (2020). Cast: Natalia Dyer, Timothy Simons, Donna Lynne Champlin, Susan Blackwell, Alisha Boe, Wolfgang Novogratz, Francesca Reale, Parker Wierling, Allison Shrum, Teesha Renee, Tre’len Johnston, Matt Lewis. Director: Karen Maine. Screenplay: Karen Maine. Web site. Trailer.

The mystique underlying highly personal subjects like sexuality and spirituality is undeniable, something that’s tailor made to our individual needs and sensibilities. So how is it that some of us feel we can dictate the terms of these matters to others, as if our views were the last word and not to be questioned? How is it that such canned perspectives can realistically fit everyone? And why must those who disagree with these outlooks be ridiculed, bullied or punished for their dissent? Those are some of the rather heady questions addressed in, of all things, the raucous but insightful new teen comedy, “Yes, God, Yes.”

Adolescence can be difficult enough all by itself, but it can be even more challenging when under the thumb of one’s peers, family and environment. So it is for Alice (Natalia Dyer), a student at a Catholic high school, presumably somewhere in the nation’s heartland. At a time when she curiously begins exploring typical teen matters, like her emerging sexuality (particularly the pleasures of “self-love”), she’s anxious to see what it’s all about, despite the harsh admonitions from her teachers and the school’s resident priest, Father Murphy (Timothy Simons), that it’s a mortal sin guaranteed to assure her a one-way ticket to hell. What’s more, in addition to such warnings, Alice (like all of her peers) is constantly reminded of the consequences of being too outwardly provocative by faculty watchdogs like the seemingly ubiquitous Mrs. Veda (Donna Lynne Champlin), who aggressively writes up students for the slightest infractions of the school’s dress code and behavioral expectations.

Needless to say, Alice cowers in nearly perpetual dread. She keeps her feelings locked up inside, afraid to admit them to anyone except her friend Laura (Francesca Reale), and even that makes her somewhat uneasy, especially when rumors about alleged but untrue erotic incidents involving her mysteriously begin circulating among her classmates. However, despite the risks involved in coming clean, she can’t deny the need to unburden herself about these powerful urges. She feels compelled, albeit reluctantly, to confess her infatuation with the steamy below-decks sex scene in “Titanic” (1997), something she watched three times in a row during a recent viewing thanks to her VCR remote’s handy rewind function. But things get ramped up even more not long thereafter when she unwittingly engages in a racy AOL chat room exchange with another user. There isn’t a shower cold enough to put out the flames of her desire.

Circumstances take an unusual change not long thereafter. While having lunch at school one day, Alice and Laura run into their once-subdued classmate Beth (Teesha Renee), who inexplicably appears to have undergone a remarkable transformation, one that has enabled her to blossom with a radiant glow. This unexplained conversion even seems to have altered Beth’s circle of friends; suddenly she’s seen in the company of the popular kids, like Nina (Alisha Boe). One could say it’s a miracle.

When Alice asks Beth what prompted this change, her luminous friend says it came about after attending a four-day religious retreat with her peers. The effect is so appealing to Alice that she’s convinced she needs to have the same experience. And so, with Laura in tow, they sign up for the getaway, to be held at a secluded wooded location.

The retreat proves to be quite a revelation, and in many more ways than Alice expected. She quickly finds she’s not alone when it comes to her emerging sexuality. In fact, her mere interest in things erotic pales in comparison to the acts engaged in by her peers, including some from whom she never would have expected such behavior. On top of that, Alice’s hormones get a supercharged boost when she’s assigned to work with a facilitator for whom she carries an enormous torch; indeed, the time she spends with Chris (Wolfgang Novogratz), a kind and handsome football player, is an exercise in excruciating restraint, particularly when he sends what appear to be decidedly mixed but nevertheless hopeful signals toward his impressionable young charge.

At the same time, though, the retreat also proves to be a difficult time for Alice, especially when she’s found to have broken some of the rules, acts that earn her penance for her “transgressions.” She also learns that she’s become the object of more rumors, some of which followed her from home and others of which arise over the course of the event. Those developments, combined with the rampant hypocrisy she witnesses, as well as the seemingly ever-present judgmentalism inflicted upon her, prompt Alice to leave the retreat during an evening campfire. She wanders along a nearby highway, eventually ending up at a roadside bar, where she meets the owner (Susan Blackwell), who proves to be the most insightful mentor she meets all weekend. Through this encounter, Alice gleans understandings about herself, her life, her sexuality and her faith that prove far more important than anything the retreat ever could have taught her. Indeed, getting away from it all can truly provide us with a fresh new perspective, one that’s more fitting and fulfilling than anything the so-called experts could ever supply – even those who claim to speak for God.

When it comes to matters as patently intimate as sexuality or spirituality, we find ourselves on some of the most personal and profound turf onto which we’ll ever venture. The decisions we make for ourselves in these areas are based on our sensibilities, choices made on the basis of our individual likes, leanings and proclivities. But what’s most important is that these determinations are ours – and no one else’s business.

Growing comfortable with such notions can be challenging when we’re in our youth. Since we’re uncertain about our world, we tend to be eminently impressionable, easily swayed by the influences around us, particularly those in seeming positions of authority. But are those authoritarian dictates what we truly believe deep down inside? Do their pronouncements genuinely resonate with who we are? And, if not, what do we do about it?

The key in bringing our own vision into being, especially when it comes to such highly personal matters, is identifying and embracing our innermost thoughts, beliefs and intents, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting the reality we experience. Of course, given the gravity involved in questions of sexuality and spirituality, we’re dealing with subjects charged with tremendous intensity and sometimes-inscrutable depth, areas in which answers may be hard to come by and choices could be easily questioned, particularly when brought under scrutiny by demanding outside sources. Under those kinds of circumstances, it’s no wonder someone like Alice, with limited life experience, might feel lost.

To grow comfortable with ourselves in these areas, we need to develop faith in our beliefs and trust their veracity. If they’re not right for us, we’ll discover that quickly enough, a signal that will tell us we’re on the wrong path and need to keep looking. But, by contrast, when they do feel right, we’ll know that, too, and likely just as fast. When we recognize that, we’ll know we’ve found what we were looking for. And this applies in virtually every area of experience, not just sexuality and spirituality.

Having come to this realization, we’ll also know how to assess the beliefs of others. We’ll be able to recognize the place, if any, that they hold in our own palette of beliefs. And, the more committed we are to our own convictions, the more we’ll be able to courageously stand up to those who assert viewpoints different from us. This is important for galvanizing ourselves in our own positions, enabling us to hold our own with others who would challenge us or try to unduly change our minds. Again, this is crucial with regard to our beliefs in any area of endeavor, but it’s especially critical for matters as personally intimate as sexuality and spirituality.

In the end, adopting such stances is essential for becoming our true, authentic selves. Allowing that portion of ourselves to come through is imperative if we hope to achieve satisfaction, joy and fulfillment in life, especially in such areas as our relationship with our bodies and our connection to the divine. And, when we see those manifestations realized, we may well be tempted to exclaim “Yes, God, yes” before grabbing for that requisite cigarette.

This charming and poignant teen comedy about a naive Catholic school girl who discovers the forbidden joys of sexuality in a generally unaccepting environment transcends the silly and unimaginative qualities often associated with films of this genre. Although the picture drags in a few spots and could stand to have been somewhat more daring at times, director Karen Maine’s debut feature serves up ample laughs without resorting to cheap tactics, often getting considerable mileage out of gestures as simple as facial expressions and other visuals that speak volumes. But, even more significantly, the film’s insights in other areas, such as judgment and self-determination, deliver spot-on messages that expose the hypocrisy and outright silliness often preached by organized religion. The picture’s superb ensemble cast, creative cinematography, impeccable editing and excellent background score add to the production’s many other fine attributes, making this release one well worth viewing. This smart, sexy, sweet offering is well deserving of all its accolades – not to mention a wide audience.

If everyone believed the same way in matters of sex and spirit, we’d have a much less colorful world. But just because we hold different viewpoints doesn’t mean we have to browbeat others into submission to get them to agree with us. In fact, when taken together, the various expressions of these issues combine to create a gorgeous mosaic, one to be admired for its beauty and diversity, the very qualities that make sexuality and spirituality such valuable and fulfilling aspects of our existence.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

Tune in for The Cinema Scribe

Thursday, July 16, 2020

This Week in Movies with Meaning

Reviews of "Portrait of a Lady on Fire," "The 11th Green" and "Balloon" are all in the latest Movies with Meaning post on the web site of The Good Media Network, available by clicking here.

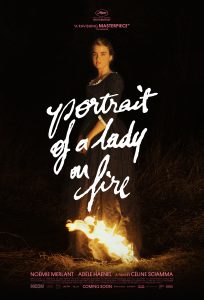

‘Lady on Fire’ fans the flames of forbidden romance

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”) (2019). Cast: Noémie Merlant, Adèle Haenel, Luàna Bajrami, Valeria Golino. Director: Céline Sciamma. Screenplay: Céline Sciamma. Web site. Trailer.

Asserting our right to openly proclaim who we love seems like a birthright we should all possess without hindrance. But, under some circumstances, doing so may be difficult, especially when we’re pressured to conform to the dictates of others. That’s unfortunately true even today, but it was far worse in the past, when social sanctions and familial obligations were much more restricting and pervasive, as illustrated in the French period piece drama, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”).

In 1760 France, Parisian artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant) is consigned to paint a wedding portrait under unusual circumstances. She journeys to an estate on the French seacoast, where she meets her client, a lonely middle-aged countess (Valeria Golino), who has asked the artist to paint a likeness of her daughter, Héloise (Adèle Haenel), whose hand has been promised in marriage to a Milanese gentleman she has never met. As straightforward as this might sound, however, the agreement comes with a number of strings attached. The most notable of these is that Marianne must paint the portrait from memory and observation, because Héloise refuses to pose for a project of this kind, a frustration that Marianne’s predecessor discovered and that eventually brought an end to his efforts at creating a finished work.

[caption id="attachment_11604" align="aligncenter" width="350"] As an unwilling subject for a consigned wedding portrait, bride-to-be Héloise (Adèle Haenel) seeks ways to get out of posing for the painting in the French period piece drama, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

As an unwilling subject for a consigned wedding portrait, bride-to-be Héloise (Adèle Haenel) seeks ways to get out of posing for the painting in the French period piece drama, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

Héloise’s unwillingness to cooperate stems from the fact that she doesn’t want to get married in the first place, especially under arranged circumstances like these. In fact, she was not to be married off in the first place, a dubious distinction accorded to her sister, who died mysteriously and unexpectedly. With her sister’s untimely demise, Héloise was tapped to fulfill the family marital obligation, a commitment she loathed to honor, mainly because, prior to her unforeseen recent return home, she had been living a contented life in a convent, a place where she enjoyed the “equality” of being entirely among women. And now, by being forced into an undesirable arrangement, she’s not about to make matters easy for those coercing her into it.

Furthermore, the countess explains to Marianne that she’s not to reveal herself as a painter to her subject. Instead, she’s to pass herself off as a “companion” for Héloise, someone to spend time with her, accompanying her on walks and engaging in other genteel activities. It’s during these times together that Marianne is to gather her impressions of her subject, sketching them from memory when by herself or discreetly without Héloise’s knowledge when they’re together. Additional details about Héloise’s character, manner and qualities are to be quietly supplied by the estate’s maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), who clandestinely helps Marianne “fill in the blanks.” And, from these memories and observations, Marianne is expected to paint the portrait, all without her melancholy subject’s awareness.

At first, Héloise is reluctant to spend time in Marianne’s company, unsure of why this mysterious, newly arrived stranger has come to the estate. She acts as if she’s constantly on guard, suspicious that her mother may have planted a spy in her midst. She often responds brusquely when conversing with Marianne, seemingly ever on the defensive. She even seems to share some of the same self-sabotage qualities of her late sister. Yet, as time passes, Héloise discovers that Marianne shares many of the independent-minded ideas that she holds dearly. She even envies her new companion, particularly with regard to the fact that she appears to have choices in her life that she herself lacks. And, as time passes, they appear to be on the verge of becoming friends.

[caption id="attachment_11605" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Parisian portrait artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant, left) and her initially reluctant subject, Héloise (Adèle Haenel, right), grow unexpectedly close the more they work together in director Céline Sciamma’s latest offering, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”). Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

Parisian portrait artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant, left) and her initially reluctant subject, Héloise (Adèle Haenel, right), grow unexpectedly close the more they work together in director Céline Sciamma’s latest offering, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”). Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

When the time comes for Marianne’s big reveal approaches, she has misgivings about having deceived Héloise. She dreads the reaction she’ll get. Yet, much to her surprise, Marianne finds Héloise unexpectedly receptive, even when she intentionally defaces the portrait as a ruse to paint a new one – and to get to spend more time with her new friend.

Needless to say, the countess is initially outraged by what has happened, calling Marianne a complete incompetent. But, when Héloise agrees to pose for the replacement painting, a startling decision that shocks the countess, she relents and allows Marianne to start over, convinced that a posed portrait could turn out even better than the one envisaged in her original plan. The artist thus gets a second chance to create the painting, to be finished by the time the countess returns from a trip.

In the countess’s absence, Marianne and Héloise begin work on the new portrait. Héloise feels a sense of liberation by posing for someone whom she considers an independent kindred spirit. They grow ever closer, developing a new level of intimacy that transcends friendship. They spend a glorious time together, their feelings of romance surfacing without hindrance or restriction.

But what’s to happen upon the return of the countess? Soon it will be time for Héloise to be joined in marriage. Will she go through with it? And what will happen to the torrid relationship that has been blossoming in recent weeks? With a woman on fire, it may be difficult if not impossible to extinguish the flames.

[caption id="attachment_11606" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Parisian artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant, right), assigned to paint a wedding portrait exclusively from memory and observation, seeks input from her reluctant subject’s maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami, left), to help “fill in the blanks” about the bride-to-be in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

Parisian artist Marianne (Noémie Merlant, right), assigned to paint a wedding portrait exclusively from memory and observation, seeks input from her reluctant subject’s maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami, left), to help “fill in the blanks” about the bride-to-be in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

At a time when women were genuinely treated as little more than chattel property, the frustrations they experienced were unbearable. The pervasive restrictions and limitations placed upon them kept them locked into incessant states of submission and subservience, with virtually no choices and almost no hope of escape from their circumstances save for the drastic measures apparently chosen by women like Héloise’s sister. And, as for Héloise, she was callously thrust into becoming a substitute for her sibling when the possibility of an obligation going unfulfilled arose, treated as little more than a commodity in a predetermined transaction. How demeaning.

Options for overcoming these confining conditions were almost nonexistent. Even beliefs in the possibility were scarce, though they were not inconceivable, even if difficult to achieve. But, to get the process moving, one at least had to be able to envision such a possibility, an outcome hatched through one’s thoughts, beliefs and intents, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these resources in manifesting the reality we experience.

In many regards, Héloise feels trapped, unable to extricate herself from these circumstances. She’s oppressed by seemingly everyone around her as they thoughtlessly and thoroughly dictate the conditions of her existence, a life that makes her time in the convent seem like an emancipated experience by comparison. She’s so disgusted by the prospect of what now awaits her that she seeks perpetual seclusion. She seems so despondent that her mother worries that she might befall a fate not unlike that of her sister, a concern that makes the countess grateful for Marianne’s presence to keep an eye on her daughter (especially for their walks along the jagged seacoast where her sibling’s lifeless body was found). She’s so convinced that there’s no escape that the only way she might be able to flee from her plight is to take matters into her own hands, an explanation for her self-sabotage tendencies.

[caption id="attachment_11607" align="aligncenter" width="350"] An unexpected romance blossoms between portrait painter Marianne (Noémie Merlant, right) and her once-reluctant subject, Héloise (Adèle Haenel, left), in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”). Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

An unexpected romance blossoms between portrait painter Marianne (Noémie Merlant, right) and her once-reluctant subject, Héloise (Adèle Haenel, left), in “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”). Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

But, much to her own surprise, Héloise finds that there may be hope for her when she becomes inspired by the example set by Marianne. Her comparatively unshackled friend provides her with a model for living life differently, a way of being more in line with what she craves. And, as this scenario unfolds, Héloise’s beliefs begin to change. Suddenly she finds herself facing the possibility that life could indeed be better than what she has typically been experiencing.

Several significant qualities accompany this unexpected change. For perhaps the first time in her life, Héloise experiences – and enjoys – the ecstasy that comes with feelings of personal liberation and independence, a rarity not only for her, but also for women in general of her time. And, as her feelings for Marianne emerge, Héloise’s passion for acting on these heartfelt instincts surfaces, a bold and impressive accomplishment given the forbidden nature of the relationship in which she engages. She no longer feels the need to deny herself what she believes makes her feel whole; the days of seeking self-imposed seclusion and solitude to cope with her circumstances become a thing of the past.

Taken together, Héloise’s embrace of the new beliefs behind these feelings and attributes represents the emergence of something even greater – her recognition, acceptance and nurturing of her authentic self, something she’s been restricted in expressing prior to this point. In fact, she’s so enthusiastic about the manifestation of her newfound self that she even inspires her inspiration – Marianne – enabling her to let her authentic self flower more profusely. At this point, Héloise is not the only lady on fire.

As Héloise becomes more aware of her authentic self, so, too, does Marianne, and in unexpected ways. For instance, it’s obvious Marianne has quite an ethical streak that runs through her being, and that’s why she feels so guilty about initially deceiving her new friend about her true self. Such behavior goes against her nature, and she’s pained by the fraud she’s perpetrated on Héloise. When she at last has an opportunity to allow her authentic self to come through, she’s thoroughly relieved. It enables her to be genuine, something that strengthens her bond with Héloise and allows their relationship to grow and prosper.

[caption id="attachment_11608" align="aligncenter" width="350"] Once-secluded bride-to-be Héloise (Adèle Haenel) becomes a lady on fire, literally and figuratively, after the onset of a torrid romance in director Céline Sciamma’s latest, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

Once-secluded bride-to-be Héloise (Adèle Haenel) becomes a lady on fire, literally and figuratively, after the onset of a torrid romance in director Céline Sciamma’s latest, “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (“Portrait de la jeune fille en feu”), available in various home viewing formats. Photo courtesy of Neon.[/caption]

What’s perhaps most important about all this is that these circumstances allow Marianne and Héloise to serve as an inspiration to others similarly situated, a development that had to have been important at a time when such sources of support and encouragement were hard to come by. This is the conscious creation concept of value fulfillment at work, the notion that urges us to be our best, truest selves for the betterment of ourselves and those around us. This is not to suggest that Marianne and Héloise were ready to lead 18th Century versions of a women’s march or Pride parade, but they quietly added their consciousness and energetic input to movements that were quietly being birthed for future emergence. Initiatives like this have to get their start somewhere, even if their materialization doesn’t occur until sometime down the road, and we have individuals like Marianne and Héloise to thank for that.

While this film has a great deal to offer – gorgeous cinematography, exquisite staging and superb performances – this French period piece drama about forbidden romance simultaneously gets weighed down by such issues as sluggish pacing, an anticlimactic and often-predictable script, extraneous story threads, and an occasional lacking in gut-level believability. Director Céline Sciamma’s latest is indeed a joy to look at, and its content certainly constitutes an earnest, heartfelt attempt at a liberated lesbian manifesto. But, despite such apparent sincerity, the film sometimes comes across as somewhat tentative and restrained in going all-out for what it really wants to say (something of an irony for a picture with a title that includes the words “on fire” in it). To be sure, this is a fine piece of filmmaking in many regards, but rising to the level of “masterpiece” – a term that has been freely bandied about in describing this film – requires more than what’s served up here. The film is available for screening in various home media formats.

The foregoing criticisms aside, this 2019 release was widely recognized in a number of competitions and at film festivals. The picture was a nominee for best foreign language film in the Golden Globe, BAFTA, Critics Choice and Independent Spirit Award contests. In addition, the National Board of Review named the picture one of 2019’s top 5 foreign films. But the film’s greatest success came at the Cannes Film Festival, where it took top honors for best screenplay and won the Queer Palm Award for best gay cinema offering, along with a nomination for the Palme d’Or, the event’s highest honor.

It seems only natural that we should be free to be who we truly are, especially in matters of the heart. Yet there are so many instances, in romance and otherwise, where others try to control us (and we, regrettably, often allow them to). But, by being willing to live our lives as our authentic selves, and by empowering ourselves with beliefs to make that possible, we have an opportunity to fulfill that burning desire to be ourselves. And, if we’re able to make that happen, we truly have an opportunity to set our lives and our world ablaze with a glory unimaginable.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Saturday, July 4, 2020

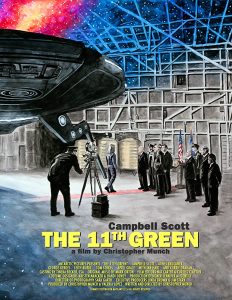

‘The 11th Green’ wrestles with the nature of truth, beliefs

“The 11th Green” (2020). Cast: Campbell Scott, Agnes Bruckner, George Gerdes, Leith M. Burke, Tom Stokes, April Grace, Ian Hart, Currie Graham, David Clennon, Monte Markham, Kathryn Lee Scott, Tom Connelly, Eli Cusick, Imani McNorton, Peter Tingstrom. Archive Footage: Harry S. Truman. Director: Christopher Munch. Screenplay: Christopher Munch. Web site. Trailer.

We all know the truth when we see it, don’t we? After all, it’s a fixed, finite concept that’s applicable to all of us, isn’t it? Or is it something more nebulous, a moving target that shifts over time? Moreover, is it something that compliantly falls in line with our observations and beliefs, or is it subject to manipulation as a result of the influence of outside sources? Indeed, it would seem that something many of us think of as infallibly reliable could be considerably murkier and less defined than we thought, either as a result of the shifting beliefs we hold about it or because of the controlling influences of others. And, in light of that, it would seem that the truth is something that’s subject to adjustment and alteration in any number of contexts, making our certainty about the nature of our existence and its components even more open to debate. These are among the rhetorical questions raised about the nature of “the truth” with regard to one particular milieu as depicted in the new speculative sci-fi offering, “The 11th Green.”

Since the end of World War II, the incidence of UFO sightings has increased significantly. These enigmatic lights in the sky – whatever they may be – have captivated, mystified and frightened witnesses around the globe in that time. And, even though instances of their apparent presence predate this period, the frequency with which they have occurred has ballooned since 1945. Yet, despite all of the anecdotal and circumstantial evidence of their existence reported by their observers, the officially stated policy of authorities regarding UFOs has been one of denial, that the so-called sightings of these aerial craft are nothing more than naturally occurring or manmade phenomena. So why the discrepancy? What is really going on here?

“The 11th Green” is a piece of speculative fiction that attempts to address these questions. Even though the film acknowledges that its story is not based on undisputed fact, the opening credits nevertheless state that it draws from what is believed to be the solid investigatory work of ufologists and researchers who have looked into the subject. The story, set in the recent past, seeks to go beyond the smoking gun about UFOs and present a narrative that explains their history from 1945 onward, including both the nature of this phenomenon, as well as the reasons behind the official cover-up to keep their existence secret.

The story is told from the standpoint of independent investigative journalist Jeremy Rudd (Campbell Scott), who provides science reports for an internet TV broadcast hosted by his colleague, Lila Parnell (April Grace). Jeremy presents reports on cutting-edge science topics, but he scrupulously sticks to dealing only in concrete evidence. And, even though he’s a closet believer in the UFO phenomenon, he never touches the subject for fear of the longstanding stigma about it in the journalism community. He believes that, if he were to broach the topic in his reporting, it would ruin the credibility of his broadcast and be the end of his career.

However, Jeremy’s hand is somewhat forced when he learns of the death of his father, Nelson (Monte Markham), a shadowy figure who has a long history of being involved in clandestine military projects dating back seven decades. The two have been estranged for some time, based largely on divergent political views, so Jeremy is not particularly familiar with what his dad has been up to for quite some time. In fact, given the secrecy under which his father operated, Jeremy’s not even sure what his old man did during much of his career. But, considering the vacuous gap between Jeremy’s progressive bent and Nelson’s conservative establishment views, the intrepid reporter never took the time to look into his father’s activities, partly out of disinterest and partly out of sheer loathing.

With Nelson’s passing, though, Jeremy is left to settle his father’s estate, most notably selling his dad’s home, a sprawling mid 20th Century ranch house that was once the residence of President Dwight Eisenhower (George Gerdes), with whom Nelson once worked in a covert capacity. Jeremy travels from his home in Washington to the California desert to wind up his father’s affairs with the aid of Nelson’s personal assistant, Laurie Larkspur (Agnes Bruckner). But what starts out as a seemingly straightforward estate settlement process soon takes a variety of unexpected twists and turns that are certain to drastically transform Jeremy’s career – and could help him break one of the biggest stories of all time.

To honor his father’s memory, Jeremy hosts an informal reception for Nelson’s friends, associates and cronies from a guest list drawn up by Laurie. The gathering includes a mix of former military, security and corporate types, as well as a professor and author well acquainted with the UFO community, Larry Jacobsen (Currie Graham). Larry, a longtime associate of Nelson, seems to be an insider with deep connections in government and the military-industrial complex who skillfully manages to play both sides of the fence, depending on which way the wind is blowing. That makes his credibility questionable, yet he somehow manages to come up with some remarkably stunning – and valid – revelations that keep him from being summarily dismissed. And, given his affinity for members of the Rudd family, Larry picks up with Jeremy where he left off with Nelson.

In short order, Larry introduces Jeremy to groundbreaking evidence about the official history of UFO secrecy, including apparently authentic film footage of a meeting between Eisenhower and an alien ambassador named Lars (Tom Stokes), a representative from a technologically advanced race that managed to overcome its social and political confrontations and thereby avoid its own self-destruction. In a covert summit, Lars delivered a message to Ike reminiscent of that shared by Klaatu (Michael Rennie), the enigmatic alien visitor in the 1951 screen classic “The Day the Earth Stood Still.” The meeting between Lars and Eisenhower thus led to an ongoing dialogue between aliens and humans that continued from the 1950s to the present, one in which each side maneuvered their way through a carefully coordinated arrangement involving matters of technology sharing, geopolitical evolution and meticulously managed social engineering regarding official disclosure of the extraterrestrial presence.

The leads Jeremy receives from Larry are helped along by additional contributions from Laurie. As they spend more time together, Jeremy and Laurie begin to draw closer to one another, transforming what starts out as an arm’s-length relationship into something more personal. But, despite this growing romantic attraction, there are also undeniable trust issues between them, concerns that Jeremy is wise to take seriously.

Besides the condolences offered by Nelson’s old pals, Jeremy also receives a letter of sympathy from one of his childhood friends, a character simply identified as “the President” (Leith M. Burke). While the name of this character is never revealed, the President bears a striking resemblance to a public official who grew up in Hawaii, where his younger self (Imani McNorton) attended an exclusive prep school with a younger Jeremy (Eli Cusick). The two classmates developed a close bond and remained friends, despite the distancing that occurred once the President ascended to the heights of his political power.

The rekindling of the connection between the President and Jeremy reinvigorates the former’s memories of his youth, including some involving peripheral interactions with a younger Nelson (Peter Tingstrom) and some paranormal experiences of his own. Recollections of these events from the President’s formative years helped prompt his interest in practices like meditation, a pursuit he engages in with the aid of guided visualization tapes. And those sessions enable various visionary experiences, including dialogues with past political figures, most notably Dwight Eisenhower. These meditative discussions reveal additional details about the incredible history of UFOs, the reasoning behind the policies of secrecy and denial, the hesitancy to proceed with disclosure, and the nature of relations with aliens like Lars. These sessions also include Ike’s accounts of the roles played by various high-profile officials through the years, including President Harry S. Truman, freshman Congressman John F. Kennedy (Tom Connolly) and inaugural Secretary of Defense James Forrestall (Ian Hart), whose mysterious suicide may have been even more unbelievable than most people think.

As Jeremy gradually (and independently) uncovers evidence of the events depicted in the meditative dialogues between the two Commanders in Chief, he begins to piece together a story more incredible than he ever imagined. But what can he do with this information? How is he to move forward? With a fitting musical backdrop featuring the overture from Richard Wagner’s Parsifal, an opera about the search for the Holy Grail, Jeremy, Lila and Larry struggle to figure out what to do with the much-sought-after iconic materials they’ve uncovered – provided they even get the opportunity to proceed with their plans.

Were Jeremy able to succeed in his efforts to tell this story, it would certainly change things drastically. In fact, that’s allegedly one of the reasons why the secret-keepers have kept matters so tightly under wraps – that the changes to society, culture and technology would be so great that it would significantly disrupt the status quo. As he comes to realize, those in power, those who would stand to lose so much, are capable of doing virtually anything to prevent that from happening. And that doesn’t even begin to take into account the effects of exposing the decades-old lie that has been used to preserve the secret. Perhaps most importantly, however, it would change the views of the world’s population at large, and those new beliefs could carry dramatic implications, particularly in light of the role they play in the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we draw upon these metaphysical resources in shaping the reality we experience.

Should these secrets be officially revealed, an entirely new worldview – one that would be difficult to manipulate and control – would likely emerge. At present, given the wide spectrum of beliefs that different individuals hold due to a lack of a consistent definitive confirmation of the UFO phenomenon, it’s easy for those who stand to lose from disclosure to maintain the fractured public consensus, forestalling those new beliefs from taking hold and reshaping our existence. That, in turn, would thwart collective co-creative efforts to shift the nature of our reality, one that could loosen the shackles of the control mongers and potentially employ the marvels of the alien visitors to re-create a vastly improved world, perhaps even an earthly paradise, one in which the clandestinely powerful no longer hold sway over the rest of humanity.

In light of that, it’s important to those who wish to stay in charge to control the message, to convince the rest of us to believe what they want us to believe, as a means of manifesting the reality that serves their needs (i.e., those in government, the military and the corporate world, the ones most likely to benefit from and cash in on this secret knowledge). If we ever hope for circumstances to change, however, we must realize this and subsequently take charge over our beliefs. We must give ourselves permission to decide for ourselves to hold fast to the beliefs that we know in our hearts are indeed true. In short, we must thus assume control of the core beliefs of our inner being, our authentic selves. In essence, to that end, to paraphrase an old adage about a common form of water fowl, if we have an experience in which we witness something that looks like a UFO and flies like a UFO, then it’s probably a UFO. Case closed.

Such measures are inherently crucial in the push for official disclosure. Through a successful co-creative undertaking on our part, that outcome could well result. But, in the process of doing this, we must carefully consider what “the truth” gets us in the end and whether we’re ready for it. We must be cautious about blindly engaging in the practice of un-conscious creation, wherein we seek our desired outcome at any cost without consideration for the consequences. For example, if we were to achieve success in securing an official confirmation of the alien presence, we must be prepared for everything that accompanies such a revelation. So what if we subsequently learn that officialdom has been keeping a lid on this secret to prevent the unleashing of detrimental forces, like extraterrestrials who have come here to harvest us as their next meal, an outcome they have been keeping at bay by keeping their efforts to combat the voracious visitors under cover? Would we really be ready for that just to have our curiosity satisfied?

Thus, in collectively seeking “the truth,” we must not only look to attain the answers we seek, but also the attendant consequences that come with it. And, to that end, we should make the effort to include that second consideration in the formation of the beliefs we employ in our co-creative undertakings. It won’t do us any good to uncover the secret if it leads to our ultimate demise; the concept of Pandora’s Box clearly comes to mind here. Given that, then, we should proceed cautiously and methodically, as Jeremy does, in seeking to discover the truth. We would be wise, for instance, to devise a scenario in which the revelation of the truth results in a friendship with Lars rather than a confrontation with the visitors from “War of the Worlds” (1953, 2005), “Independence Day” (1996) or the movies in the “Alien” franchise.

In the end, however, this enigmatic sci-fi tale, which fuses elements of “The X-Files” and a variety of other movies and television shows, is a bona fide cinematic conundrum, one that probably requires viewing with an enormous grain of salt. To be honest, director Christopher Munch’s latest has more than its share of shortcomings, including pacing issues, excessive talkiness, considerable (and I do mean considerable) extraneous and easily edited material, a needlessly convoluted screenplay, and yet another uninspired monotone performance by Campbell Scott. Nevertheless, to its credit, the film also presents one of the best, most thorough and most comprehensive treatments of the dark history of UFOs, the cover-up to conceal the many secrets associated with this phenomenon, and how all this has affected both the movement for disclosure and many aspects of everyday life and culture. The speculative yet insightful and enlightening approach used in addressing this subject helps to make up for the picture’s other failings, though it’s unfortunate that the other aspects of the film don’t match up with this admirable and informative strength. Those who readily dismiss “conspiracy theories” are likely to easily laugh this one off, but those who sincerely take a broader, more open-minded view of things will find this an inspiring take on a subject that could hold tremendous promise and potential for our future. The film is currently available for first-run online streaming.

Because truth and beliefs would appear to be more relative than most of us tend to think, it’s important that we recognize that as such, for that kind of variability can have far-reaching ramifications, even affecting the very nature of the existence we experience, both overall and in its myriad facets. Given that, it’s incumbent upon us, then, to make sure we’re clear about their nature, especially in jointly created ventures, to come up with the desired results. Indeed, as avid golfers (like President Eisenhower) well know, ending up on the green is what every linksman hopes for, especially in light of the alternative – getting stuck in the rough.

Copyright © 2020, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Wednesday, July 1, 2020

This Week in Movies with Meaning