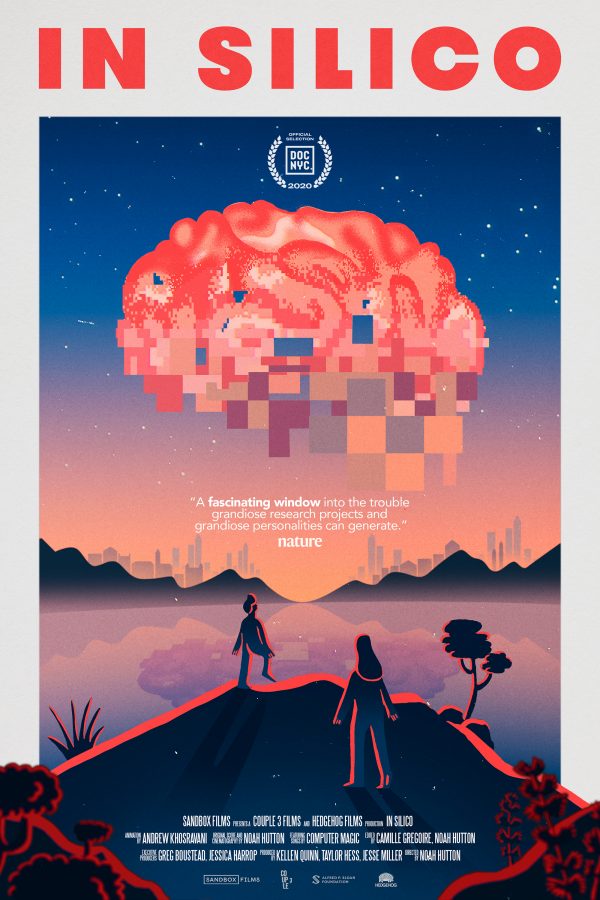

“In Silico”(2020 production, 2021 release). Cast: Henry Markram, Zachary Mainen, Sebastian Seung, Christof Koch, Noah Hutton (narrator), Garry Kasparov (archive footage) Kai Markram (archive footage). Director: Noah Hutton. Screenplay: Noah Hutton. Web site. Trailer.

Unlocking the mystery of existence is an exacting, enigmatic, and, at times, exasperating study that often leaves us with more questions than answers (especially when any answers we find lead to more questions). Many of us don’t even know where to begin our investigations, either, though, over time, we’ve come to find that our brains and/or consciousness generally provide good starting points. But, even if we make any progress in these areas, we usually discover that the process is bigger and more complicated than we ever imagined, as a visionary scientist and his team of associates found out for themselves in the captivating new documentary, “In Silico.”

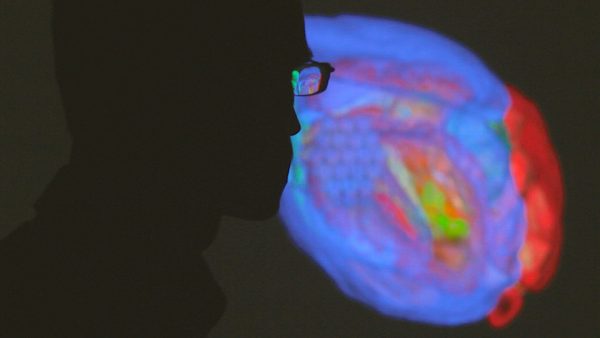

The brain is a truly remarkable phenomenon of nature. But how much do we really know about how it was created and how it functions? We’ve been able to identify which areas of the brain deal with particular kinds of bodily and consciousness functions, but what sparks this extraordinary organ into action, creating the various manifestations that result? And how did it come into being in the first place?

Filmmaker Noah Hutton, a longtime student of neuroscience, always wondered about these questions and wanted to make a movie about the subject. He eventually found his inspiration after seeing a TED Talk in 2009 given by visionary Israeli scientist Dr. Henry Markram of the Swiss research institute l’École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL). After years of investigating brain architecture, Markram’s studies took a drastic turn, addressing questions of how and why the brain works as it does. In particular, he was curious about why the behavior exhibited by his young autistic son, Kai, differed so markedly from those unafflicted by that condition. What was causing his brain to operate so differently from everyone else? Indeed, what triggers in Kai’s head were prompting his neurons to fire in ways unlike the rest of us?

As Markram pondered these questions, he wasn’t necessarily looking for a cure for autism but for an understanding of the way that brain comes up with its signals and how they are then transmitted to produce the various behaviors that they’re intended to yield. To grasp this, Markram believed he could uncover the answers by constructing a computer model that would mimic the functioning of a brain, providing insight into how specific behaviors resulted from various kinds of triggering inputs. He would begin by creating a simulation of a rodent’s brain as a stepping stone to doing the same later for more advanced animals, like man. This represented quite an audacious undertaking, but Markram was convinced he could achieve his primary objective in 10 years. And that’s when an impressionable and fascinated Hutton signed on to document the progress of the project.

Studying brain function from this standpoint was largely uncharted territory. Traditionally, neuroscience had been considered a purely biological undertaking using one of two available investigatory methodologies: in vivo studies, in which nerve cells in living beings were examined (an unacceptable option where human brains were concerned), or in vitro studies, wherein cells were cultured and researched on petri dishes (an inadequate approach for these purposes). Given what Markram was hoping to achieve, he needed a new approach to neuroscientific research, one that examined the principles of biology in a computerized environment, a technique that would come to be known as in silico.

Launching an endeavor like this called for the establishment of a significant infrastructure of its own, both in terms of funding and staffing. Working through the Brain and Mind Institute, an organization founded by Markram at the EPFL, the researcher went on to establish a new investigatory body, the Blue Brain Project, which introduced the digital element of this initiative. (“Blue” in the project’s name refers to “Big Blue” – IBM – the company that created the computer equipment for the venture, much of it based on “Deep Blue,” the supercomputer that took on Russian chess master Garry Kasparov in a match in 1997.) Generous funding was provided by the Swiss government, and a team of collaborators in areas ranging from biology to computer science to ethics was assembled.

In 2013, after several years of work, it became apparent that this initiative was going to be a bigger project than originally thought. To secure additional financial resources, Markram and his team submitted a bid for a €1.3 billion flagship research grant from the European Union. Although considered something of a long shot to win this prestigious endowment, Markram’s new venture – the Human Brain Project (HBP) – was named one of two winners from a pool of six applicants vying for funding. Markram’s compelling case, coupled with a growing interest in brain research studies around the globe at the time, helped secure the award for HBP.

However, even with such generous backing and apparent validation, the study soon came under criticism. Skeptics questioned the viability of the project, a process that was already under way before the awarding of the grant but that gained steam afterward. For example, considering how many different ways that humans behave, would it indeed be possible to identify the brain waves responsible for triggering each of them? Given the breadth of human consciousness and the myriad permutations of its expression, attempting to categorize such a broad range of behaviors based on brain wave functions, they contended, was akin to trying to quantify infinity. Skeptics also questioned what they saw as an unrealistic timetable. Even though the 10-year timeline was reset with the awarding of the 2013 grant, attaining the sought-after goal by 2023, they claimed, seemed woefully inadequate.

Before long, even those who had initially enthusiastically supported Markram’s proposal were beginning to pull back, primarily because of this emerging criticism. One of the most vocal skeptics was neuroscientist Zachary Mainen of the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown in Lisbon, Portugal, who contended that Markram was attempting to build a composite working model from individual components whose specific functioning wasn’t completely understood, analogizing the process to assembling a watch from parts that might ultimately resemble a time piece but that would be incapable of telling time. Adding to this, former MIT multi-disciplinary scientist Sebastian Seung speculated that, even if computer-generated brain waves could be created, how could anyone tell if these simulations were right or wrong for what they were supposedly intended to achieve? Could brain waves thought to be associated with the creation of a painting actually result in a finished portrait, or would they manifest something wholly divergent?

Such criticisms put quite a damper on the project. Markram chalked up the disparagements to neuroscientific traditionalists not fully appreciating the value of this new approach to brain research. He was also upset that Hutton had spoken with the critics. And, as time passed, he came under increasing pressure to make concessions on how HBP would proceed, requests that he resisted. As a result, Markram began to be viewed as inflexible, holding fast to aspirations that couldn’t possibly be attained but that he would not let go of. He continued to champion his cause publicly, even beginning work on his own film about the project. As claimed by another of his critics, Christof Koch, president of the Seattle-based Allen Institute for Brain Science, Markram “has two personalities. One is a fantastic, sober scientist…the other is a PR-minded messiah.”

These issues culminated in the publication of an open letter signed by 800 neuroscientists globally, calling for a restructuring of the project. By 2016, Markram had been removed as leader of the initiative he created, and priorities were rearranged. He continued to claim that his goal was achievable, even though he was taken less seriously than before.

As for Hutton, he admits to being torn about how matters ultimately played out. After all, he had just invested 10 years of his life to the making of this documentary. Part of him was still enthralled by the wide-eyed idealism that launched this film project, yet another part had become weighed down by the contentions of the critics (credible though they may have been), a splash of cold water on the enthusiasm he once so heartily embraced. He thus had to reconcile that youthful fervor with the setting in of a discouraging but undeniable reality.

One might find it disillusioning that something so noble and ambitious as this project could get derailed by considerations as comparatively mundane as management and money. However, anything that hypothetically seeks tangible manifestation must contend with the practical matters associated with such implementation. So it was here. But that’s not to say this is the end of it, either. Given the conceptions that the human brain has been able to devise, there’s no telling what else it might accomplish down the road. Sometimes all it takes is asking the right questions or putting forth the right notions to get the ball rolling toward such an eventuality. And, for what it’s worth, Henry Markram may have done just that, even if the current state of the logistics needed to accomplish that haven’t yet evolved to the requisite state.

When we embark on a new endeavor, we often start out with boundless enthusiasm and a cheerful bravado. That’s especially true when we launch into new ventures that hold the promise and potential of breaking new ground, leading to revelatory discoveries and exciting, never-before-imagined prospects. But, many times, once we start digging into the nitty gritty aspects of such undertakings, we often run into snags, particularly unanticipated obstacles that slow the process and sidetrack us from our principal objective. We might well become dismayed at having to set aside our primary efforts to address seemingly ordinary considerations. We may be frustrated at having to invest time, energy and other resources on matters we view as trivial or distracting, despite their necessity to the project. And, if we’re not careful, we could become ensnared by these issues, stalling much, if not all, of our forward progress, perhaps even causing us to lose sight of our original goal and becoming distressingly discouraged. Such is what Henry Markram came up against the further he got into his project.

So what’s to be done? That’s not an easy question to answer. Perhaps the best solution is to try to accommodate such considerations up front, at the start of a new undertaking. However, it can be difficult, perhaps even deflating, if we dilute our enthusiasm and divert it into comparatively menial concerns. Who would want to dampen one’s visionary zeal by having to devote time to pondering trivial matters like the fine points of logistical planning, administrative oversight or financial management when potentially exciting, groundbreaking developments await?

Nevertheless, as anyone who has ever undertaken an endeavor like this knows, the devil truly is in the details, and they can’t be ignored, no matter how much we might like to. Which, once again, reminds us of the importance of trying to accommodate such considerations as much as possible from the outset. This can best be accomplished by envisioning what we hope to achieve, preferably in detail, and then formulating beliefs on how we might accomplish it. Such is the nature of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we manifest the reality we experience – in all of its aspects – by drawing upon the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents.

Ironically, the launch of Markram’s venture in many ways mirrors the essence of conscious creation itself. He sought to understand how the mechanics of the brain lead to the manifestations that emerge in our existence (be it our behavior, the products of our vocations and so forth) and then to construct a computer model to simulate the workings of that process. In many ways, this was essentially a tangible reflection of the mechanics involved in the unfolding of an intangible metaphysical protocol. It was also an embodiment of several key conscious creation principles, such as thinking outside of the box and pushing through limitations. At its core, this project was aimed at advancing our knowledge and understanding of how the ideas that appear in our heads arise in our existence as tangible materializations, perhaps giving us new perspectives on how reality works and a new appreciation of the role of consciousness in the unfolding of this process.

The foregoing illustrates the audacity of Markram’s vision. But, considering how events played out, the boldness of that undertaking was at least partially undercut by the challenges associated with more pedestrian issues. This naturally raises the question, why did this happen?

Definitive answers on this point may well be elusive. However, in all likelihood, the focus on the project’s primary goal was so strong that the other considerations weren’t factored into the overarching manifesting beliefs as thoroughly as they likely needed to be. In all fairness, it’s unclear whether Markram was even aware of the conscious creation process and its functioning, let alone how they played a role in this venture. But, from a speculative standpoint, while his beliefs were apparently driven principally by the project’s scientific elements, the other aspects were ultimately just as important, because they supported its tangible unfolding. The failure to address them to the requisite degree thus led to this deficiency in the belief mix responsible for bringing the project into being.

Fully formulating the belief mix in any manifestation is crucial to its successful realization. It involves making allowances for all of the factors involved in a fleshed out materialization, including elements that may seem unrelated to its fulfillment. The visibility and presence of these aspects may not be obvious, but, like the framing of a house or the infrastructure of a community, these elements are important parts of the project, providing the necessary foundation to support its existence. Thus it’s critical to consider the interconnection of these components, and the beliefs that bring them into being, to see how they make up the complete whole.

The criticisms that emerged in the wake of this project’s unfolding illustrated some of the venture’s “underdeveloped” aspects. This occurred not only in the logistical matters, but also in some of the project’s technical considerations. For example, the notion that it might be possible to identify all of the conceivable brain wave patterns responsible for all forms of behavior, creation and other brain-driven activities seems somewhat implausible in light of the breadth of the field of permutations involved and the proposed timetable. Perhaps the research team should have considered pursuing a more modest, more manageable goal instead, one that might have engendered wider support. That, in turn, might have fostered more amenable acceptance in other areas related to the project’s backing and objectives.

As the film observes, the brain is a complex organ that’s not always well understood, and its functioning – particularly how it interfaces with something as intangible as consciousness – is even more enigmatic. And trying to understand the entire range of its operation is nearly impossible given our current level of knowledge. So, if we’re trying to determine how we can get a better handle on this, Hutton suggests, perhaps we should draw from our experiences in studying other elements of human anatomy, such as the heart. He notes that, as our cardiac investigations advanced, we came to amass quite an understanding of the organ’s functioning. With that information in hand, researchers were thus able to identify which qualities were most sought after in the promotion of a healthy, efficiently functioning heart, traits that are integral to the principles underlying modern cardiac care. Hutton says that, if we could comparably narrow the focus for the brain, we might be able to get a better handle on the organ’s functioning and management – or at least a start on that process.

Still, there’s no guarantee that such scaled-back or derivative proposals would work. As Hutton observes at several points in the film, there have been many instances in planetary biological evolution where advances have occurred as a result of “happy accidents,” incidents where unexpected and/or unlikely events have transpired that brought about miraculous new developments, including, apparently, in the structure and operation of the human brain. One might legitimately ask how such seemingly “random” occurrences could result in light of such an apparently deliberate process as conscious creation, and, admittedly, the answer to that question might not be readily forthcoming. Perhaps our knowledge and awareness have not advanced to the point where we can understand or appreciate how such phenomena unfold, but that doesn’t mean they can’t evolve further at some point, either. Maybe, if we attempt to intentionally expand our cognition in these areas, the answers will be revealed, and the aforementioned developments won’t be seen as accidents at all.

In reaching that point, though, the process has to start someplace. By opening the door to new possibilities, we have an opportunity to advance our knowledge and understanding, perhaps even to the point where we unlock the mysteries of those happy accidents. Markram’s project could be one of those openings. Even if he didn’t or hasn’t come up with the definitive answers he sought when he launched his venture, that doesn’t mean the endeavor is without merit. He might very well have helped pave an avenue of exploration for subsequent researchers who will eventually come up with workable solutions and meaningful answers. BBP and HBP could be the baby steps that lead us to profound depths of knowledge about the brain and consciousness that aren’t currently known or understood. Should those developments arise, not only will it silence the critics, but it will benefit us all with a greater awareness about our world, ourselves and how our reality comes into being. That’s quite a prospect, even if we can’t or aren’t yet ready to see it.

What we expect to find may not always end up being what we ultimately do find, and so it is with this eminently engaging documentary. What seemingly starts out as a chronicle of mindful scientific exploration takes an unexpected turn as it delves into an analysis of the behind-the-scenes workings of that discourse. Nevertheless, despite such “detours,” the film always comes back to the science that inspired it, presenting an array of highly technical topics in an easily relatable way. At the same time, though, director Hutton’s offering also paints a candid portrait of the highly competitive (and sometimes less than civil) world of bidding for research funding. In addition, the film examines “the big questions” of whether the study of these issues rightfully falls within the scope of science or philosophy (or some combination of the two) and whether such ethereally tricky conundrums can even be quantified or properly evaluated given our current level of knowledge and understanding. Hutton, Markram and other commentators give us all much to think about, and they do so in plainspoken terms, bringing the relevance of these sophisticated scientific subjects down to an everyday level and not letting them linger in the realm of abstract, inaccessible theoretical speculation. The result is an impressive cinematic work, one befitting this ambitious decade-long film project. “In Silico” is available for streaming online through the film’s web site.

While it may be tempting to want to know how all of the foregoing works, perhaps we’re not ready for it yet, which is why the mysteries remain hidden. That’s not to say we won’t be prepared for the answers at some point; with every new discovery, we learn a new piece of the puzzle, ever increasing our understanding and moving us closer to a deeper awareness. Until then, we should enjoy the journey that’s taking us there, relishing the wonders of the brain, consciousness and reality as they are revealed to us. And, for the time being, that gives us plenty to marvel at, showing us just how captivating and fulfilling the study and appreciation of existence can be.

Copyright © 2021, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment