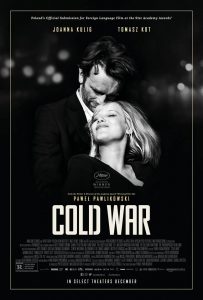

‟Cold War” (“Zimna wojna”) (2018). Cast: Joanna Kulig, Tomasz Kot, Borys Szyc, Agata Kulesza, Cédric Kahn, Jeanne Balibar, Adam Woronowicz. Director: Pawel Pawlikowski. Screenplay: Pawel Pawlikowski, Janusz Glowacki and Piotr Barkowski. Story: Pawel Pawlikowski. Web site. Trailer.

Even when we get all the breaks, sometimes life just doesn’t satisfy us. We pursue the opportunities that present themselves, but somehow they inevitably fail to live up to their billing (and our expectations), leaving us feeling unfulfilled. And, if this pattern continues unabated, at some point, we may grow despondent, perhaps engaging in various forms of unproductive or even self-destructive behavior. So it is for an entertainer who has a chance to have it made and ends up sabotaging herself at every turn, a saga chronicled in the melancholic new Polish drama, “Cold War” (“Zimna wojna”).

In 1949 Poland, not long after the fall of the Iron Curtain over the Soviet satellite states of Eastern Europe, the government commissions a pair of professional entertainers, musician Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot) and choreographer Irena Bielecka (Agata Kulesza), to scour the country in search of candidates for a troupe of singers, dancers and musicians to give high-profile public performances at home and in foreign lands celebrating traditional Polish folk art. While Wiktor and Irena have some freedom to choose who they want, their work is closely scrutinized by their government sponsor, Lech Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc), who’s concerned that the candidates selected are suitable artistically, politically and ethically, upstanding model citizens of contemporary Communist Polish society.

One aspiring singer, Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig), captures everyone’s attention. During her audition, the beautiful young vocalist reveals her angelic singing voice. But she also appears to possess a wealth of other qualities that intrigue Wiktor, both personally and professionally. As musical director of the troupe, he takes a special interest in her, seeking to mold her into a featured performer. There’s just one problem: She carries some heavy baggage, having been charged with stabbing her father and being placed on probation. It’s not the kind of reputation that sets well with Kaczmarek, who fears that, if her secret were revealed, it might disgrace the troupe and its prospects for the future.

[caption id="attachment_10470" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Polish émigré Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig) delivers cool but steamy renditions of numbers from her homeland in Parisian nightclubs in director Pawel Pawlikowski’s award-winning new offering, “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

Polish émigré Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig) delivers cool but steamy renditions of numbers from her homeland in Parisian nightclubs in director Pawel Pawlikowski’s award-winning new offering, “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

Wiktor, however, believes that he can manage Zula and keep her skeletons barricaded in the closet. He convinces Kaczmarek to let her become a member of the troupe, and, as the troupe begins touring, Zula is a stand-out sensation, contributing significantly to its popularity and artistic accomplishments. What’s more, the more Wiktor works with Zula over time, the closer they become personally, eventually striking up a torrid but somewhat clandestine romance.

At the same time, Kaczmarek, who also quietly longs for Zula, secretly strikes a deal with her to spy on Wiktor, a condition of her probation aimed at ensuring her loyalty (and, hence, her continued participation in the troupe). Kaczmarek’s interest in keeping tabs on Wiktor stem from suspicions about the director’s commitment to the government’s objectives for the troupe. For instance, Kaczmarek takes note of Wiktor’s less-than-enthusiastic response to a government “suggestion” that the troupe begin performing pieces other than just traditional Polish folk songs, namely, propaganda-based compositions dealing with subjects like land reform and wealth redistribution. Also, given that Wiktor is assumed to be somewhat more free-thinking because of his artistic sensibilities, Kaczmarek can’t help but wonder whether the musical director can truly be trusted.

[caption id="attachment_10471" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Singer Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig, right) and musical director Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot, left) engage in a torrid romance across Europe in the Oscar-nominated feature from Poland, “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

Singer Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig, right) and musical director Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot, left) engage in a torrid romance across Europe in the Oscar-nominated feature from Poland, “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

As it turns out, Kaczmarek has good reason to have his doubts. During a concert date in East Berlin in the days before the Wall was built, Wiktor hashes out a plan to defect to the West, and he asks Zula to join him. Because of her renegade ways and the feelings he believes she holds for him, Wiktor assumes she’ll join him without question. And, when the time comes to carry out his plan, he successfully makes his move, eventually finding his way to Paris. But Zula surprisingly stays behind, continuing her performances with the troupe. It’s a decision she later regrets, prompting her to find a way to emigrate to Paris, a goal she eventually fulfills.

Thus begins an on-again/off-again romance across a divided continent in which Zula and Wiktor each spends some time in the West and some time in the East, ever searching for the elusive happiness they seem to crave but are never able to find, both personally and professionally, not to mention romantically. Along the way, they have involvements with other partners – Wiktor with a French poet (Jeanne Balibar), Zula with a French filmmaker (Cédric Kahn) and even with Kaczmarek – but they always seem to come back to one another, only to part ways again, that is, until they come up with a unique solution to their unhappiness.

[caption id="attachment_10472" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Aspiring performer Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig, second from left) takes director for choreography instructor Irena Bielecka (Agata Kulesza, second from right) in “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

Aspiring performer Zula Lichon (Joanna Kulig, second from left) takes director for choreography instructor Irena Bielecka (Agata Kulesza, second from right) in “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

“Cold War” is, at times, a frustrating film to watch. One can’t help but hope that Wiktor and Zula will find what they’re looking for, but the picture shows what it means to search for what one wants and never finding it. The protagonists try to claw their way through a maze of self-destructive behavior, some of it understandable, some of it completely inexplicable. It might be tempting to chalk things up to the oppressive conditions under which they live in Communist Era Poland, but, when they’re in the freedom that Paris affords, they seem just as unsatisfied as they were in Warsaw. In many ways, this is a sort of personal hell from which escape seems impossible. There must be a way out, though finding it may be more of a challenge than either of them realizes.

How do such circumstances arise? As in any scenario, they come from our thoughts, beliefs and intents, the building blocks of the conscious creation process, the philosophy that maintains we use these tools to manifest the reality we experience. And, based on what Zula and Wiktor create, they obviously don’t have a handle on what they want for themselves. The conflicted nature of their beliefs becomes apparent in the conflicted nature of their existence.

Clearly, Zula and Wiktor are unable to define what makes them happy, a deficiency reflected in their beliefs and resulting life experiences. One would think that the freedom of the West would be ideal to individuals living under the restricted conditions of the East. However, when someone who is accustomed to rigidly controlled certainty is suddenly presented with unlimited choices, the range of available opportunities can be overwhelming, making it virtually impossible to decide what to select. For Zula, these types of circumstances even predate those that came into effect with the Communist takeover of her homeland; given the household in which she grew up, she obviously suffered the controlling influence of a domineering father, one whose ways eventually led her to lash out at him, as evidenced by the stabbing incident.

[caption id="attachment_10473" align="aligncenter" width="300"] The efforts of Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot, left), musical director of a Polish performing troupe, are scrutinized by government official Lech Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc, right) to ensure that he adheres to expected official dictates in the new award-winning drama, “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

The efforts of Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot, left), musical director of a Polish performing troupe, are scrutinized by government official Lech Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc, right) to ensure that he adheres to expected official dictates in the new award-winning drama, “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

When such a fractured outlook becomes ingrained, sooner or later it’s not out of the question for it to lead to questionable behavior, such as the inexplicable acts in which Zula and Wiktor each engage. It’s sad that they’re unable to find a solid footing for their beliefs, because, as conscious creators well know, the process can indeed make any outcome possible as long as we’re focused on what we hope to achieve. But, when one is unable to grasp that fundamental understanding, the result can be chaotic and disappointing, conditions that may lead to desperate measures to find happiness and peace of mind.

Interestingly, the relationship between Zula and Wiktor in many ways parallels the rocky relationship between the West and the East that was going on around them, that they, too, were experiencing a “cold war” of their own on a much smaller but equally turbulent level. Wiktor, who’s all too ready to defect to the West and the possibilities it presents, symbolizes the realm to which he wishes to escape. Zula, on the other hand, who seems more comfortable with controlling influences governing her, represents the authoritarian regime of the East, one that seeks compliance from its constituents regardless of what they may want personally (even if they can figure that out). When you take two individuals with such polarized sensibilities and put them together, is it any wonder that they would have difficulty forging a successful relationship? And, when you combine with that an ability to choose what would make them happy, it’s easy to see why Zula and Wiktor had such an on-again/off-again romance.

[caption id="attachment_10474" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Seeking artistic freedom during the early 1950s, Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot), musical director of a Polish performing troupe, seeks to make his escape to the West while on a concert date in East Berlin in “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

Seeking artistic freedom during the early 1950s, Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot), musical director of a Polish performing troupe, seeks to make his escape to the West while on a concert date in East Berlin in “Cold War.” Photo by Lukasz Bak, courtesy of Amazon Studios.[/caption]

For better or worse, such a result is also a product of conscious creation, even if the characters themselves are unaware of it. The beliefs they hold about themselves and the society of which they’re a part permeates their being and every aspect of their daily lives. It’s tragic, though, that they never seem to be able to get it together. Let’s hope we can learn from this cautionary tale and find for ourselves the fulfillment that seems to ever elude them.

This gorgeously filmed, sublimely cool story of troubled romance pays fitting homage to European art films of the 1950s and ʼ60s with a narrative somewhat reminiscent of the French drama “Betty Blue” (1986). Beautifully shot in black and white, director Pawel Pawlikowski’s bittersweet tale features an outstanding performance by Kulig, both in her musical numbers and her diverse dramatic scenes. However, after a strong beginning, the picture begins to meander somewhat toward the middle, as if the director didn’t quite know how to bridge the opening to a conclusion that he already had in mind. It feels like all the makings of a great film are here but that they don’t quite gel as well as they might have in the finished product. See it for the gorgeous cinematography and Kulig’s outstanding performance, but don’t be surprised if you come away from it feeling somewhat like the unsatisfied protagonist.

Despite these shortcomings, the film has been lavished with praise in recent award competitions. At the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, “Cold War” won the award for best director and earned a Palme d’Or nomination, the event’s highest honor. Subsequent to that, the picture was named best foreign language film by the National Board of Review. And, in upcoming contests, this offering has captured three Oscar nominations (best foreign film, director and cinematography) and four BAFTA Award nods (best foreign film, director, original screenplay and cinematography). Previously the picture also received a Critics Choice Award nomination for best foreign language film.

It's regrettable, perhaps even tragic, when we’re unable to see the good fortune that blesses us. But, for what it’s worth, sometimes that’s not enough to give us what we believe we need to make us feel happy and fulfilled, be it in our love lives, our vocational callings and our very appreciation of life. Stories like those depicted in “Cold War” may sadden us, but one would hope that they leave us grateful for what we have – and make it possible to wish the same to others.

Copyright © 2019, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Friday, February 1, 2019

‘Cold War’ charts the rocky road to peace of mind

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment